According to Xenophon’s version, Socrates allegedly behaved honorably and majestically at the trial, and he considered his best defense to be his life up to that point. Socrates was not afraid of punishment, because by that time he had already “considered death to be preferable to life”. He supposedly did not think over his defense speech because he was forbidden by the “gods” themselves, and it was they who suggested to him that it was time to die and opened the easiest way to this goal. But death turns out to be preferable to life for him not because some “post-mortem” will be better than life on earth. That, of course, is also the case, but it is hardly mentioned in Xenophontes’ version. His arguments in favor of death were very down-to-earth, and here he complains about senile difficulties and lack of pleasures. It turns out that here too the argumentation is presented through the prism of sensationalism (as in “Hiero” and “Oeconomicus”). And as it was already mentioned about the dialog “Hiero”, Socrates here also speaks about the “mental” ability to love as one of the most important abilities of a human being in principle. But what is most interesting are Socrates’ own words in response to the judges’ accusations. Here Xenophontes, clearly constructing the character to suit himself and his own views (as, indeed, did Plato), makes Socrates adore Sparta:

However, Athenians, the god expressed an even higher opinion of the Spartan legislator Lycurgus in his oracle than of me. When he entered the temple, they say, the god addressed him with this salutation: ‘I do not know whether I should call you god or man.’ But he did not equate me with a god, but only recognized that I was far above men.

…

Do you know a man who is less than I am a slave to the passions of the flesh? Or a man more unselfish, taking neither gifts nor payment from anyone? Who can you recognize with good reason as more just than one who is so comfortable with his position that he needs nothing from anyone else?

…

And what is the reason why, although everyone knows that I have no means of repaying with money, yet many people wish to give me something? And the fact that no one asks me to repay a favor, but many recognize that they owe me a debt of gratitude?

Not that Socrates himself did not love Sparta, obviously he did (Plato also points to this), but it still seems a very strange speech at the trial, too meaningless a digression, unless the Laconophilic views were part of the prosecution itself (and indirect indications suggest that this was the main motive for his trial). Otherwise, Socrates’ style of defense is very similar to what we see in Plato’s Apologia. We see that Socrates here is still the same snob, claiming to be a superhuman being surrounded by common people. But the dialog is interesting because here the accusers specify their accusations, and it becomes clear that “corrupting youth” implies literally the following things: Socrates allegedly makes young men «obey you more than their parents ” and, in essence, teaches them sophisms. And if Plato is to be believed, he was literally teaching sophisms, even if for a noble purpose. Xenophontus understands so well what Socrates is being attacked for and why, that he even appeals to us:

If some people on the basis of written and oral testimonies about Socrates think that he could turn people to virtue perfectly well, but was not able to show the way to it, then let them consider not only those conversations of his, in which he with an edifying purpose with the help of questions refuted people who imagined that they knew everything (i.e. Plato’s dialogues), but also his everyday conversations with his friends, and let them then judge whether he was able to correct them.

In Xenophon’s account, Socrates behaves much more restrained at the trial, and his arguments are already much more solid, and one even gets the feeling that Socrates was actually slandered. He is an ordinary virtuous man who does not engage in such pranks as assigning himself a dinner at the expense of the state as a punishment (in Xenophont’s case he will not assign himself anything because he does not admit his guilt). Xenophontus supports the “meme” about Socrates as an “ethical philosopher” who was not engaged in “physics” because of its uselessness (after all, it is impossible to change planets even after learning the principles of planetary motion, and why study something that is not in our will and is generally useless for life?)

And he did not argue about the “nature of everything”, as others do for the most part; he did not touch the question of how the “cosmos” so called by philosophers is organized and according to what immutable laws every celestial phenomenon takes place. On the contrary, he even pointed out the folly of those who deal with such problems.

And by this he tries to say that Socrates does not coincide with what Aristophanes said about him in his comedies. Apparently, this also seemed to be an important part of the accusation, if one has to justify oneself in this way. Here Xenophontes also adds that physics is not useful because all physicist-philosophers disagree with each other and give different theories of matter, motion, etc. The only problem is that the same problems apply to the same ethics… but this example is interesting even just as an illustration of the Greeks’ attitude toward the abundance of “systems” and their mutual contradiction. Since there are so many of them, they are all equally false. This was one of the most likely reasons why the Sophists chose to state relativism. Socrates apparently decided, on the same grounds, to simply state the futility of physics, and did not decide on full relativism. But these are just interesting details, and the main thing is different. The most interesting thing in Xenophontes’ system of excuses seems to be that he himself gives examples that essentially bury Socrates and prove his guilt.

What was Socrates being tried for?

The dialog we are about to describe is a textbook example of Socratic sophistry. If it is to be believed, it turns out that Socrates was accused of corrupting youth at least three times, at different periods of Athenian history, under the rule of quite different people: (1) during the Peloponnesian War (Aristophanes’ comedy); (2) after the defeat and under the rule of oligarchs and tyrants (our example); and (3) after the return of democracy (the execution itself). It turns out that this was not a random pretext, but a long-running problem. And the following illustration from Xenophon makes us agree with the charge as never before! This plot goes like this:

After the victory over Athens and under the patronage of the Spartans, the regime of the “Tyranny of the Thirty”, led by one of Socrates’ disciples (not even one, but at least several, but the main figure was Critias), launches a roller of repression, which affected the aristocrats. Socrates was very indignant about this and allegedly said:

“It would be strange, it seems to me, if a man, having become a shepherd of a herd of cows and reducing the number and quality of cows, did not recognize himself as a bad shepherd; but it is even stranger that a man, having become the ruler of the state and reducing the number and quality of citizens, is not ashamed of it and does not consider himself a bad ruler of the state”.

When the tyrants Critias and Charicles were informed of this, they called Socrates to themselves, showed him a certain law and forbade him to speak to young men. One can say that this is a formal reason for punishment, but these same people unceremoniously executed even their own associates (e.g. “the tyrant of thirty” and Theramenes, who was close to Socrates in his views), and here, for some reason, instead of showing him the same things as his associates, they forbid him to communicate with young people! This is a very strange change of subject, and a very mild punishment. It is very hard to explain this behavior. Perhaps the explanation lies in the tyrants’ personal respect for Socrates, who knows? But after such a ruling, Socrates got the right to ask questions about the points he allegedly did not understand:

Well, I am ready to obey the laws; but in order that I may not imperceptibly, through ignorance, break the law in something, I want to receive from you precise instructions about this: why do you order to abstain from the art of speech, — is it because it, in your opinion, helps to speak rightly, or wrongly? If — to speak rightly, then, obviously, one would have to refrain from speaking rightly; if — to speak wrongly, then, obviously, one should try to speak rightly.

That is, when he was demanded to stop practicing sophistry, he literally answers in the face of tyrants with a sophistic device. One might suspect that he did this deliberately in such a defiant manner to show his protest. Thereupon “Charicles became angry” (you bet he did), and said:

When, Socrates, you do not know this, we announce to you this, which is more understandable to you, — that you should not speak to young men at all.

It is clear that this radicalization was more of a rhetorical one, so that Socrates would get the gist of the claim. But Socrates continues to ironize, and to engage in just what he is being asked to stop doing:

— Thus, lest there be any doubt, define to me until how old people should be considered young.

— Until they are allowed to be members of the Council, as men as yet unwise; and thou shalt not speak to men under thirty years of age.

— And when I buy something, if a man under thirty years of age sells it, neither should I ask how much he sells it for?

— About such things we can. But you, Socrates, mostly ask about what you know; so don’t ask about that.

Socrates is told bluntly that both he himself and they all know what the problem is, and that the question is solely on the subject of teaching young men sophistic techniques! But Socrates continues to play the fool:

— So I should not answer if a young man asks me about something I know, such as where Charicles lives or where Critias is?

— About such things it is possible, — answered Charicles.

Then Kritius said: No, you have to, Socrates , give up these shoemakers, carpenters, blacksmiths: I think they are completely worn out from the fact that they are always on your tongue.

You can’t get any straighter than that. He is literally asked not to piss people off in the streets with examples of narrow specialists who are “supposedly wise”, when wisdom is not available to anyone. Young men listen to this and then mock their parents in the same way. Socrates is told, not for the first time, “please stop”. But Socrates is inexorable!

— ‘So,’ replied Socrates, ‘from the things that follow — from justice, piety and all that sort of thing?

— Yes, by Zeus,” said Charicles, ”and from the shepherds; otherwise, see how you do not reduce the number of cows.

And here Xenophontus decides that the reason is not that Socrates has been pestering Athenians for more than 30 years, and therefore most citizens do not like him, but only that the tyrants took offense at the metaphor about cows and shepherds! And since then, taking Socrates’ lawyer at his word, all literary criticism considers it not another example of condemnation for corrupting the youth, but an example of banal offense of tyrants who did not understand the greatness of Socrates. In general, this dialogue is given here not by chance, but as evidence in defense of Socrates. If Critias subjected Socrates to repressions, and Socrates himself considered Critias a bad man — then the fact that Critias was a pupil of Socrates loses its significance. He was a pupil, but his teacher condemned him, and they went their separate ways. The second figure with bad fame, among the students of Socrates, was Alkiviades, an ambitious commander, who during the war several times ran from camp to camp, but if averaged, he was a “populist” and rather a supporter of the democratic party of Athens. Alkibiades was also killed by Critias, but still this did not make him a good man in the eyes of the Athenians.

Xenophontus gives us an example of how Alkibiades learned how to debate from Socrates, but immediately adds that once he realized that he had defeated Pericles in debate, he immediately decided that he didn’t need anything more from Socrates. This is used as a rare case and a private example of real “spoiling of youth”, but in general Socrates is not responsible for the bad character of Alkibiades. Alkibiades and Critias are supposedly just two bad examples, and all the other disciples of Socrates are saints. Let us even suppose that this is true. But much more interesting is what Alkibiades learned from Socrates, and how he “defeated” Pericles in an argument. This is one of the examples that speak of Xenophontes (and Socrates, Plato, and all associated with them) as a rigid conservative.

— ‘Tell me, Pericles,’ began Alkibiades, ‘could you explain to me what law is?

— ‘Certainly,’ answered Pericles.

— Then explain to me, for the sake of the gods, — said Alkibiades, — when I hear people praised for their respect for the law, I think that such praise has hardly the right to receive someone who does not know what the law is.

— Do you want to know, Alcibiades, what the law is? — Pericles answered. — Your wish is not difficult to fulfill: laws are all that the people in the assembly will accept and write with an indication of what should be done and what should not.

— What thought the people are guided by in this — good should be done or bad?

— Good, by Zeus, my boy, — answered Pericles, — certainly not bad.

— And if not the people, but, as happens in oligarchies, a few people gather and write what should be done — what is it?

— Everything, — answered Pericles, — that will write those who rule in the state, having discussed what should be done, is called law.

— So if also a tyrant, who rules in the state, writes to the citizens what should be done, and this is law?

— Yes, — answered Pericles, — and everything that writes the tyrant, while the power is in his hands, is also called law.

— And violence and lawlessness,’ asked Alcibiades, ‘what is it, Pericles? Is not it when the strong forces the weak not by persuasion, but by force to do as he pleases?

— ‘I think so,’ said Pericles.

— So, everything that the tyrant writes, not by persuasion, but by force forcing citizens to do, is lawlessness?

— It seems to me, yes, — answered Pericles. — I take back my words that everything that the tyrant writes, without convincing citizens, is law.

— And all that is written by a minority, without convincing the majority, but using their power, should we call it violence, or should not?

— It seems to me, — answered Pericles, — everything that someone forces someone to do without convincing, — no matter whether he writes it or not — will be more violence than law.

— Then what the whole nation writes, using its power over the wealthy without convincing them, is more violence than law?

—Yes, Alkiviad, — answered Pericles, — and we in your years were masters of such things: we were busy with it and invented the same things, which, apparently, busy now and you (this, apparently Pericles realized that caught on sophism).

Alcibiades said to this:

— Ah, if, Pericles, I had been with you at the time when you surpassed yourself in this skill!

In the eyes of Xenophontes, Alkibiades had won, and proved that democracy = tyranny of the majority over the minority. And he learned it from Socrates. This is not a bad example, but an example of success, after which Socrates was no longer needed by Alkibiades, and therefore, after such a “base” — Alkibiades became corrupted, and he himself became no better than Pericles and tyrants.

It turns out that Xenophontus literally shows that Socrates even in other regimes and by other people was accused of corrupting the youth, as well as the fact that he was an engaged supporter of the aristocracy (and this in a democratic regime, in the very one where he was finally executed, could be an additional argument in favor of execution). Xenophontus even expands the variation of the charges, and speaks of more such charges: (1) “Socrates taught contemptuous treatment of fathers, he inculcated the belief that he made them smarter than their fathers, and he inculcated disrespect not only for fathers but also for other relatives”. (2) «Socrates of the most famous poets chose the most immoral places and inculcated criminal thoughts and the desire for tyranny ”.

Of the first we have already spoken; only the connotation changes here. But the second is very interesting. From the point of view of the democratic regime, indeed, Socrates sought to overthrow democracy, and this in any form is already “tyranny”. Xenophontes, on the other hand, presents his own ideas about the term “tyranny”, and, of course, Socrates did not propose such a term (cf. how a Marxist proves that Stalinism is not fascism, referring to his own definitions of fascism). Two specific quotations were allegedly cited against Socrates, and Xenophontus fights them off without difficulty. Of course, being the author of the book, Xenophontus can paint his accusers as fools; and in the way it is presented to us, it is hard to disagree. But what quotations are given (the quotations themselves at least should not be spurious)? These are:

1) “Work is by no means alone disgraceful, but disgrace is only idleness.”

2) A lengthy quote from Homer about Odysseus striking with his rod Tersitus, who dared to speak out against the aristocracy in the name of the people.

In the first case Xenophontus tries to convince us that Socrates meant agitation for labor, in the spirit of the Communists. In the second case, we have a not particularly convincing excuse that Socrates, using Tersitus as an example, supposedly condemns all those who shake the boat of the state, not just the poor. And while the second quotation is such a classic moralizing example of aristocrats that everything is clear here; the first might well have meant that any means are good for overthrowing democracy. In the context of all the things Socrates says outside the court — these quotes were really used as political. But as part of the justification, he suddenly starts to mean “other”. However, Xenophontes, which is especially funny, managed to shove the quotation of Theognides (a man who in poetry calls almost to cut the throats of nobles in the name of aristocracy) directly into Socrates’ defense speech at the trial. The very lines Socrates uses are very neutral out of context, and are about how citizens should be educated:

From the noble you will learn goodness; but if with the bad.

You will lose your former mind.

And there may not be any subtext here. But the very fact of such citations says something, at least about what literature Socrates was oriented to. The noble is Theognides’ = aristocrats, and the “bad” is the people/crowd. It goes without saying that Socrates did not quote the harshest things from Theognides, for which aristocrats love him, in his defense at the trial, because he is not a complete fool. But he could have quoted it:

With a strong heel crush this unreasonable nigger to death.

Beat it with a sharp heel, bend its neck under the yoke.

But he was presented with a quotation from Homer about Tersitus, which is as close to this theme as possible. If it really was one of the most popular quotes in Socrates’ repertoire, it is very hard to get away with it. For us all this is important only because even in the acquittal speeches Xenophontus managed to add weight to the accusation, and a little better revealed the line of attack of Socrates’ enemies.

The political position of Socrates and his disciples

The only thing to be said about Socrates’ accusation is that you don’t really get executed for such a thing. So in any case the judges were wrong. But it should be understood that they were not “wrong” in the charges themselves, they are not blind and stupid, as the whole scholarly community still says. It’s just that even if Socrates did all the things they charged him with, it wasn’t a violation of the laws of Athens, and so yes, the persecution was purely political. For that matter, we too would have condemned the execution of Socrates and stood in his defense, just as we should have condemned the attempted executions of Anaxagoras and Protagoras. It doesn’t matter that Socrates was a fascist bastard, the law didn’t forbid him to be one. If he had to be put down, it would have been better to do it outside the judicial system.

Just now we can sort out whether Socrates was a “fascist” and what his political views really were. Here we will look at Xenophon’s Greek History. One of the most interesting events here is the last major victory of Athens over Sparta during the “Peloponnesian War”. The very battle after which all the victorious generals were put on trial and executed. It is this event that Xenophontus and Plato emphasize, showing that Socrates was then almost the only person from the panel of judges who opposed this decision and tried to save the strategists from execution. This example in their eyes proves Socrates’ patriotism. Usually this event (see “Trial of the strategists” on Wikipedia) is discussed in the abstract. The people executed the generals for not even attempting to rescue survivors and pick up the bodies of fallen allies after the battle. The defense usually claims that a storm prevented them from doing so. This is a religious issue because not picking up the bodies of the fallen was considered horrible blasphemy. What is surprising here is that Socrates and Xenophontes, who are always on the side of maximizing religiosity, in this case put efficiency above religious tradition. Here we can suspect that they were not satisfied with the very fact that victorious generals are judged by some blacks, and all other circumstances are secondary. Or we can simply say that they thought here as pragmatists. There are many variants, but the reasons for the execution, and the reasons for the defense of Socrates, hardly had a partisan character.

Be that as it may, it is important to record that Socrates here was against the condemnation, while one of the accusers was Theramenes. In that campaign it was Theramenes who was ordered to take away the dead, but he could not, referring to the storm. They could hang all the dogs on him, but he justified himself in such a way that it turned out that the generals themselves did not know whether the weather was normal or not, but just went home without a second thought. And Feramen at least tried, and besides, he had a subordinate position, so it was not the highest responsibility. The generals tried to sink Feramen, but in the end he sank them.

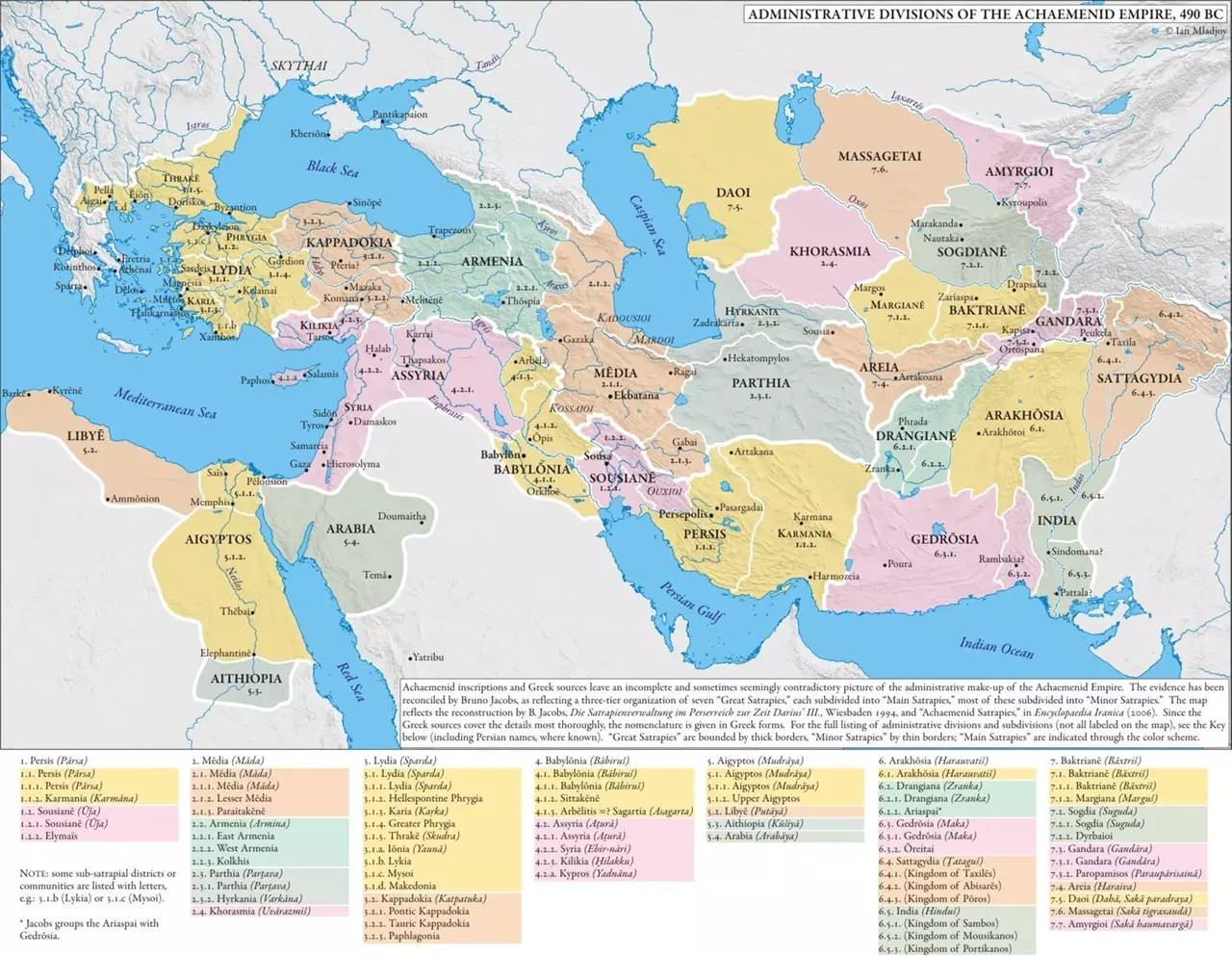

After this event, Sparta was able to gain the support of Cyrus, the prince of Persia, and with his money and fleet — defeated Athens. Xenophontus in his book exults on this occasion and relishes every move of Sparta and every humiliation of the Athenians. The final peace treaty, i.e. in essence capitulation, was signed by the very same Theramenes. How Socrates felt about it, we can only guess. Now the Athenians had to establish oligarchic rule, as elsewhere in the territories subject to Sparta.

This oligarchic system began in this way: the people decided to elect thirty men to compile a code of laws in the spirit of the old days; these laws were to form the basis of the new state system.

Thus began the “Tyranny of the Thirty”, at the head of which stood the student of Socrates — Kritias, as well as another uncle of Plato — Harmides, and many aristocrats close to them. The top of the “thirty” included Theramenes. Moderate conservatives, such as Xenophontes, were dissatisfied with the fact that the issuance of “laws in the spirit of antiquity” delayed, and thus, “thirty” indefinitely prolonged their stay in power. And the power was used for repressive purges, both in the camp of democrats and among discontented aristocrats (that is why the tyranny was condemned by Socrates, Plato and Xenophontes). And for their own safety, the “thirty” requested Sparta to garrison Athens at the city’s own expense.

The next important moment in the “History” Xenophontes — is the image of the opposition that opposed the tyranny of the thirty. It was headed by Theramenes. It should be understood that this character is far from an exemplary ideal, and in addition to the fact that he was among the “tyrants” and appeared in the case with the fleet, he became famous for the fact that he changed parties and ran from camp to camp several times. The same Alkibiades was reviled by everyone for the same behavior. Like many conservatives, Theramenes was in the circle of Socrates, but also in the circle of the sophist Prodicus. He was one of those who led the oligarchic coup of 411, but he also became the one who strangled this coup. And it was Theramenes who made the final peace with Sparta. Just as in the previous coup he was among the leaders of the oligarchy, but was horrified by their “righteousness”, and opposed, the same thing happened in the case of the “tyranny of the thirty”. Theramenes criticized almost every move of Critias. Let us recall that Kritias began arbitrary repression, took away the arms of all citizens, and granted political rights to only 3000 Athenians chosen at his own discretion, not to mention that he introduced a Spartan garrison of his own free will. Resistance on the part of Theramenes began to frighten Critias, so he too fell under the gusher of repression.

Theramenes was accused, to cut a long story short, of not adoring Sparta enough. From the defense of Theramenes we will cite only the most basic of his personal political position. He is a patriot of Athens, and wanted to see a conservative Athens, not a copy of Sparta. He was particularly incensed that Critias had executed many aristocrats, simply for not being principled enough in their hostility to democracy. Among other things, Theramenes even condemned the exile of such future leaders of democracy as Thrasybulus and Anitus. Yes, the same Anitus who would later judge Socrates. From Theramenes’ point of view — this only strengthened the enemies of the aristocracy:

Do you really think that Thrasybulus, Anitus and the other exiles would be more eager to see the kind of order that I seek to bring about here than the state of affairs to which my co-rulers have brought the state? No, I think that in the present state of things they are convinced that they meet with implicit sympathy everywhere; but if we succeeded in bringing the best elements of the population to our side, they would consider the very idea of ever returning to their native land almost unfulfilled.

It is evident that the positions of Feramen and Anita are diametrically opposed. From what has already been said, it is clear that he is not even a moderate democrat, but he is not a supporter of Critias either. This can be called “moderate” or “classical” conservatism. He himself describes his position as follows:

I, however, Kritias, all the time tirelessly fight the extreme currents: I fight with those democrats who believe that the real democracy — only when the government involves slaves and beggars, who, in need of drachma, ready to sell the state for drachma; I fight and with those oligarchs who believe that the real oligarchy — only when the state is ruled at will by a few unlimited lords. I have always — both before and now — been in favor of a system in which power would belong to those who are able to defend the state from the enemy, fighting on horseback or in heavy armor. Come on, Critias, show me a case in which I have tried to remove good citizens from participation in public affairs by siding with extreme democrats or unlimited tyrants.

And even within the framework of the laws that the Thirty had enacted, Theramenes was going to be acquitted. But Critias decided to kill Theramenes outside the framework of his own law. The scene of his murder is very long and pathos-laden, but we won’t drag it out. The main thing here is that Xenophontes treats Theramenes with obvious sympathy, despite all the “controversial” sides. It would seem that Socrates, Xenophontes, Plato, and all the members of their circle (among whom, among others, was the same Kritias!), all of them were supporters of Sparta and aristocracy. Why, when their comrade and like-minded Kritias finally took power and began to realize their ideals — they supported Theramenes? What does that mean? They were not supporters of Sparta? No, it means they were moderate conservatives like Theramenes. This politician is a manifestation of their political ideas. The question was only about the degree of radicalism, not the substance of the ideas themselves.

And here it is interesting to add that of the extant sources, the most praise for Theramenes was given by such conservative-minded supporters of the Socratic/Platonic tradition as Isocrates and Aristotle. Aristotle even called Theramenes the ideal model of a politician. Later, the historian Diodorus would even write a scene that is considered to be not authentic (for Socrates’ disciples would obviously have mentioned it if it were true), but which clearly appeared for a reason:

Theramenes bore the misfortune courageously, for he had learned from Socrates the deep-philosophical view of things, but the rest of the crowd sympathized with Theramenes’ misfortune. No one dared to help him, however, for he was surrounded on all sides by a mass of armed men. Only the philosopher Socrates and two of his disciples ran up to him and tried to wrest him from the hands of the attendants. Theramenes begged him not to do so. “Of course, he remarked, I am deeply touched by your friendship and courage; but it would be the greatest misfortune for myself if I should find myself responsible for the death of men so devoted to me.” Socrates and his disciples, seeing that no one was coming to their aid, and that the arrogance of their triumphant opponents was increasing, ceased their attempt.

Suppose, let us say, that this is a fiction. But Diodorus clearly felt that Socrates’ group was ideologically in line with the ideals of Theramenes. It is not surprising (given Theramenes’ own speeches above) that when Anitus returned to power, Socrates’ group fell under the gusher of repression, not immediately, but still fell. They were moderate but still laconophiles.

Systematic philistine v. Epicurus

But if even Socrates was rightly accused of corrupting the youth (at least in the paradigm of Athenian public opinion), then from Xenophon’s point of view, Socrates’ bad reputation was to blame for his dialogues with citizens, which were later recorded by Plato. Xenophontus, as we have seen, thought it unfair to judge Socrates only from this side, and tried to show what he was like in his narrow circle of friends. In these conversations Socrates tells us the philistine “base” about intelligent design, i.e. that God created everything for a purpose, and that grass was created for the sake of the cow’s stomach, and her stomach for the sake of grass (teleology). He also talked about abstaining from all pleasures, respecting one’s parents, etc., etc., a general conservative base. In one of many dialogues, Socrates takes the opportunity to reveal his ideas about teleology (target causes), and in the process prove the existence of gods. Teleology itself is a bastardization of thought that doesn’t even deserve criticism (seriously, just read the arguments in its favor). But Socrates is not just stating his views to the ceiling, but by talking to a certain opponent named Aristodemus. It so happens that this man in his argumentation anticipates Epicurus, and for this reason he is worth our attention. Touching upon teleology, they moved on to the more global question of whether the gods take part in our lives at all, and Aristodemus insists that they do not. Here we see the justification of the deism position .

Noticing that he does not sacrifice to the gods, does not pray to them and does not resort to divination, but, on the contrary, even laughs at those who do it, Socrates addressed him with the following question:

— Tell me, Aristodemus, are there people whose wisdom you admire?

— Yes, — he answered.

— Give us their names,” said Socrates.

— In epic poetry I admire Homer most of all, in dithyramb — Melanippides, in tragedy — Sophocles, in sculpture — Polycletus, in painting — Zeuxides.

— Who do you think deserves more admiration, — is it he who makes images devoid of reason and movement, or he who creates living beings, intelligent and self-motivated?

— By Zeus, much more the one who creates living beings, if indeed they become so not by some accident but by reason.

And after the standard arguments of teleology in the spirit of “the gods created the cow so that man could have milk”, and the gods gave us reason to compensate for the lack of fur and claws, by which Socrates supposedly proves a constant care for us (and in fact only care during the act of creation, that’s in the best case), Aristodemus expresses a typical Epicurean attitude to the gods.

— Is there nothing sensible anywhere else? Can you really think so, knowing that the body contains only a small part of the vast earth and a tiny fraction of the vast amount of liquid? In the same way, from each of the other elements, which are undoubtedly great, you have received a tiny particle for the composition of your body; only the mind, which, therefore, is nowhere to be found, by some happy accident, do you think you have taken it all for yourself, and this world, vast, boundless in its multiplicity, do you think it is due to some madness that it remains in such order?

— Yes, by Zeus, I think so: I see no rulers there, as I see masters in the works here.

— Nor do you see your soul, but it is the mistress of the body: therefore, if you reason thus, you have a right to say that you do nothing by reason, but everything by chance.

Here Aristodemus said:

— No, Socrates, right, I do not despise the deity, but, on the contrary, I consider him too majestic that he needs still reverence on my part.

— If so, — objected Socrates, — then the more majestic the deity, which, however, dignifies you with his care, the more you should honor him.

— Rest assured, — replied Aristodemus, — if I had come to the conviction that the gods at least some care for people, I would not treat them with disdain.

In general, in relatively small texts Xenophont touches directly on a lot of issues. Among them are the issues of art, where Socrates gives evaluations close to the positions of classicism. For example, in a conversation with the artist Parrassius, Socrates proves that the artist is capable of expressing mental qualities by conveying emotions in the movements of statues, in facial expressions, and in the depiction of the gaze. Whereas Parrhasius himself, up until this conversation, believed that “intangible” things could not be depicted. So overall yes, we see a very conservative, idealistic thinker who can even be called religious. Not only does he honor the gods, but literally every action requires to be accompanied by sacrifices in favor of the gods. But it is funny that Xenophontus accuses Plato of giving Socrates a bad reputation, saying that it was he who made the teacher look like a sophist clown. While Xenophontes himself left no less unpleasant examples for Socrates. In some places he does it even more harshly than Plato. Take, for example, the story about the dispute between Socrates and his student, the hedonist Aristippus (it turns out that there are more careless students than just Critias and Alkibiades).

One day Aristippus took it upon himself to knock Socrates down, just as he himself had been knocked down by Socrates before. But Socrates, having in mind the benefit of his interlocutors, answered him not as people who fear that their words will not be interpreted in some other sense, but as a man convinced that he is just doing his duty. The case was like this: Aristippus asked Socrates if he knew anything good. If Socrates had named something like food, drink, money, health, strength, courage, Aristippus would have argued that these were sometimes evil. But Socrates, meaning that if anything bothers us, we look for means to get rid of it, gave the most dignified answer:

— ‘You ask me,’ he said, ‘do I know anything good for fever?

— ‘No,’ replied Aristippus.

— ‘Perhaps for eye-sickness?

— ‘Neither do I.

— How about for hunger?

— Not from hunger either.

— Well, if you ask me if I know anything so good that it is not good from anything, I do not know it, and I do not want to know it.

That is, when Socrates was presented with exactly the same questions with which he himself asks everyone — he answered that either he would give a private definition (like the sophists), or he would not say anything. This is what all his interlocutors do. But only they are dumb, and Socrates is smart. Apparently, Socrates is smart only in that he did not let himself be drawn into this. But already here it becomes obvious that Socrates himself treats the “Socratic dialogues” as a mockery. In another fragment Socrates in general responds identically to the sophists, but according to Xenophontes it is all very wise:

Aristippus asked him if he knew anything beautiful.

S: Even many such things.

A: Are they all similar one to another?

S: No, as unlike some as possible.

A: So how can the unlike be beautiful?

S: And this is how: a man who is beautiful in running, by Zeus, is not like another who is beautiful in wrestling; a shield, beautiful for defense, is as unlike as possible to a throwing spear, beautiful for flying fast with power.

A: Your answer is not at all different from the answer to my question whether you know anything good.

S: Do you think that good is one thing and beautiful is another? Don’t you know that everything in relation to the same thing is beautiful and good? So, first of all, about spiritual virtues it cannot be said that they are in relation to some objects something good and in relation to others something beautiful; then, people are called both beautiful and good in the same respect and in relation to the same objects; also in relation to the same objects the human body seems both beautiful and good; equally, everything that people use is considered both beautiful and good in relation to the same objects in relation to which it is useful.

A: So is a dung-basket a beautiful object?

S: Yes, by Zeus, and a golden shield is an ugly object, if for its purpose the former is made beautifully and the latter badly.

A: Do you mean to say that the same objects are both beautiful and ugly?

S: Yes, by Zeus, as well as good and bad: often what is good for hunger is bad for fever, and what is good for fever is bad for hunger; often what is beautiful for running is ugly for fighting, and what is beautiful for fighting is ugly for running: because everything is good and beautiful in relation to what it is well adapted for, and, conversely, bad and ugly in relation to what it is badly adapted for.

Xenophontes’ version is an unusual character altogether; his version of Socrates holds that although people are of different qualities from birth (for physiological reasons), education plays a huge role and virtue can be taught. On this point he is again hardly different from the Sophists. And in one of the sketches Xenophontus even shows Socrates interacting with the hetaera Theodotas. When the students began to talk about popular rumors about her beauty, Socrates decided that it is not enough to listen, it is necessary to evaluate it! And he led the whole crowd of listeners to her, and he evaluated her very highly, and, in fact, began to openly flirt with her (!).

— So how could I arouse hunger for what I have? — Theodota asked.

— And here’s how, by Zeus, — replied Socrates. — First of all, if you will not offer it, or remember when people are full, until they will not pass the feeling of satiety and will not appear again desire; then, when they have a desire, you will remind them of it only in the most modest form, so that it does not seem that you yourself impose on them with your love, but, on the contrary, that you avoid it, until finally their passion does not reach the highest limit: at that moment, the same gifts have a much higher price than if you offer them while there is still no passion.

Here Theodotus said:

— Why don’t you, Socrates, hunt for friends with me!

— Well, if only you persuade me, — replied Socrates.

— And how can I persuade you? — Theodotus asked.

— You think about it yourself and find such a way, if there is a need for me, — replied Socrates.

— So you come to me more often, — said Theodota.

In the end, of course, Socrates will turn on the irony and excuse himself from dating, hinting that he has some better “girls” (and by girls he means his friends-students) and therefore it is unlikely that he will have enough time for one more. But the very fact that Socrates quietly visits hetaera, and is not ashamed of their society (Socrates is even proud of his friendship with Aspasia, the wife of Pericles, the leader of democracy and an enemy of Sparta), attends feasts, and behaves there like an ordinary partygoer (see “Feast” by Xenophontes); all this makes him, on the one hand, an ordinary man without the aplomb of an “ascetic philosopher”, but on the other hand, shows him from the side of an ordinary sophist of his time.

The only thing that makes Socrates special, sharply different from other sophists, is his principled advocacy of the principles of meritocracy. Professional managers should rule, and all things should be done by specialists in their field (whereas the sophists insisted that everyone could do as many different things as possible). Moreover, the notion of “happy life”, which Socrates, like Democritus, makes the central notion of philosophy, is associated with virtue in the sense of “doing good deeds”, i.e. with active civil life on patsan notions (cf. Stoics). Otherwise, he is conservative, traditional, religious, but as a rule “moderately”, without fanaticism. An ordinary patriarchal man, which in modern times are plentiful in every run-down village. I would say that in modern terms Socrates is more of a “right-wing radical” than a fascist; and in the realities of that time, his political representative could be the aristocrat Theramenes.