When we talk about English Romanticism in the 19th century, everyone thinks of Byron and his friend Percy Shelley. However, among the lesser-known authors of this period, there were masterpieces that are known to everyone today. One of the most striking examples is Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Percy’s wife. Despite the popularity of the image of Frankenstein’s monster, Mary’s name is little known among the famous authors of the nineteenth century. Thanks to cinema, Frankenstein is perceived as a story about a monster and the triumph of science. In fact, this is a misconception, and Mary’s novel is underestimated, just as she is underestimated. The philosophical issues that run through her work raise more significant questions than the works of her famous contemporaries. In this article, we will try to recreate the true meaning of her novels and consider Shelley’s work beyond the monster story.

Mary Shelley’s work is a transitional phenomenon that contains specific features of English Romanticism, which are determined by the peculiarities of the socio-economic situation in English society. The Industrial Revolution, and especially the introduction of steam engines, led to the rapid growth of cities and the destruction of entire sectors of the old craft economy. Such dramatic changes greatly exacerbated social problems. Thus, a real «army of the unemployed» emerged, and the overcrowding of cities created such demographic pressure that newly arrived citizens were forced to cram into small barracks in unsanitary conditions. Needless to say, this led to an increase in mortality and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. And this is not to mention the fact that, as a result of the state policy of supporting local landowners (i.e. aristocrats), England had the most expensive bread in Europe. As a result of these problems, the intellectual environment of England began a critical review of the attitude to the prospects of social development and scientific and technological progress that had been formed in the eighteenth century. This explains the moderation of the ideas of the English Enlightenment.

In part, it was this crisis of Enlightenment ideology that gave rise to the Romantic worldview. However, the late English Romantics (at least those in Byron’s circle, including the Shelleys) remained to some extent faithful to the traditions of the previous stage in literature, which allowed them to combine past and new trends in their work.

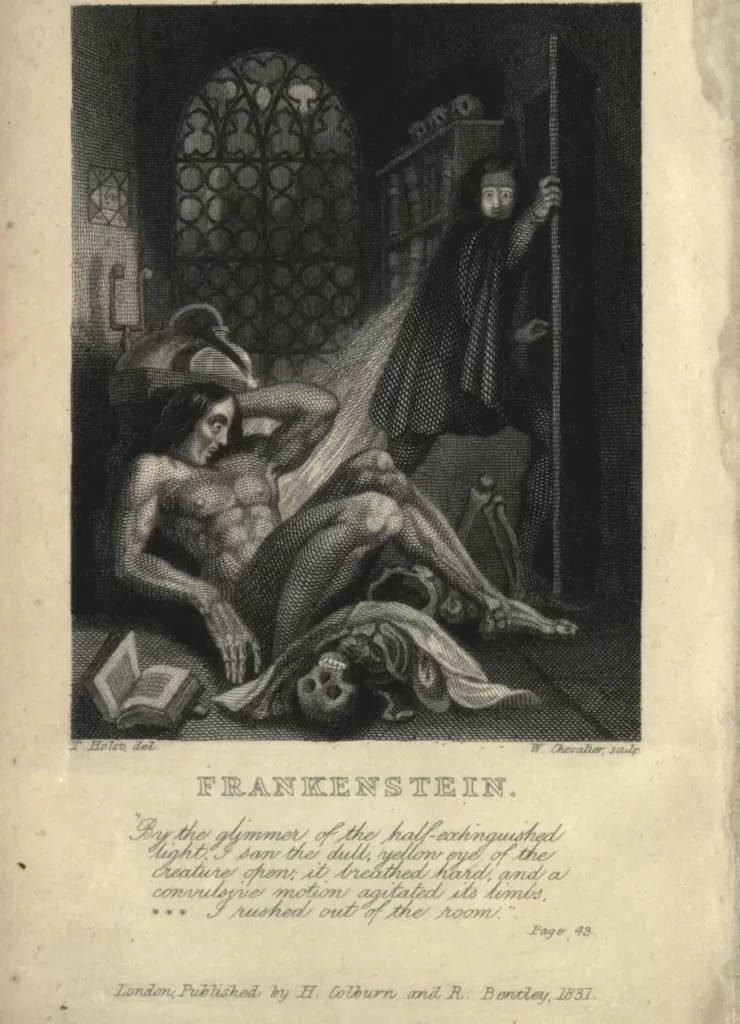

Mary Shelley’s most famous work was the novel Frankenstein or a Modern Prometheus (1818), which was highly praised by Byron and Walter Scott. At the same time, the works written later show that Mary Shelley’s talent developed gradually. Thus, the novel «The Last Man» (1826), numerous articles and reviews reflect the writer’s active participation in contemporary literary controversies. «Valperga» (1823) and «Perkin Warbeck» (1830), written in the genre of historical novel, very popular in the early nineteenth century, follow the traditions of Walter Scott. The novels Lodore (1835) and Faulkner (1837), created later, reflect the processes that took place in the 1830s in British literature — the movement from Romanticism to Victorianism. Mary Shelley’s works are a vivid example of the literature of this transitional period, and this partly explains their content.

The novel The Last Man (1826) emphasizes Mary Shelley’s transition to a new level of creative maturity. In addition, there are semantic and artistic similarities with her novel Frankenstein. Both of these works personify myths: «Frankenstein is the myth of «creation,» and The Last Man is the myth of «destruction.» Although they are different in essence, certain connections can be found in them. This concept is reminiscent of the poetry of Byron, whose poems also echo «creation» and «destruction,» namely, the poem «The Darkness» (1816), in which humanity dies by giving up the struggle, and the poem «Prometheus» (1816), in which humanity continues to struggle despite the hard struggle and high price.

Unrelated in plot, Shelley’s novels resonate on different levels. The first novel, as we said earlier, is an interpretation of the myth of «creation.» The failure of Frankenstein’s daring attempt shows the inability of man to equal God as a creator. In The Last Man, the failure of man as a creator is transformed into the powerlessness of man in general. Thus, the myth of creation turns into a myth of destruction. If the demon created by Frankenstein can still be called a «failed Adam,» then Lionel Verneuil, the protagonist of The Last Man who survived the epidemic, wanders the devastated earth as an «Adam in reverse.» And if Byron’s pessimistic poem was followed by an optimistic poem, Mary Shelley’s novels develop the theme in the opposite order, the plot of destruction completes what was already started in the not-so-optimistic story of creation. Unlike Byron, here we see gloomy prospects in general.

The peculiarity of these novels is Mary Shelley’s ideological and philosophical polemics with both past generations of authors and contemporaries. This is most noticeable in the novel The Last Man, which rethinks the ideas of the Enlightenment and Romanticism in an ironic way. The polemic is supported by philosophical and social motives, primarily the themes of human loneliness and the limitations of science. Thus, Frankenstein’s voluntary and selfish alienation from society is reflected in Verneuil’s story. He loves his loved ones, does his best to be useful, but just like Victor Frankenstein, he is powerless to save other people. In addition to this plot similarity, both novels open with epigraphs from John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

In both cases, we can speak of an «open» ending that leaves room for the reader’s imagination. This allows us to interpret Frankenstein and The Last Man as part of a philosophical dilogy. It is worth talking about all these similarities, as well as differences, in more detail to see how Mary Shelley’s work refracts the entire worldview of her era.

The image of Prometheus and the tragedy of the enlightened mind

The full title of the novel, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, directly refers to the myth of Prometheus, whose influence is clearly seen in Mary’s work. The image of Prometheus as the personification of the titanic struggle of man was actively used in romantic literature, and the myth of him inspired the greatest authors of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For the English romantics who turned to the story of Prometheus-Byron (whose poem was mentioned above), Percy and Mary Shelley-the main source of inspiration was the tragedy Prometheus Chained, attributed to Aeschylus. At the same time, there are significant differences in the interpretation of this story among the above-mentioned authors. Firstly, Percy Shelley and Byron choose the poetic form of presentation, while Mary Shelley chooses the prose form. Secondly, in Byron’s poem «Prometheus» as well as in Percy’s lyrical drama «Prometheus Unbound» the myth of the titan performs a plot-forming function; while in Mary Shelley’s novel, the image of Prometheus turns into a metaphor, and only the plot scheme remains from the myth. This scheme is difficult to recognize without the subtitle «Modern Prometheus.»

Mary Shelley borrowed the name «Modern Prometheus» from Anthony Shaftesbury, who used it in his works The Moralists (1709) and A Counsel to the Author (1710). It turns out that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the interpretation of the image of Prometheus was used much earlier than the Romantics. At the same time, if for Byron and Percy the images of rebellion and the struggle against enslavement are important as such, Mary Shelley uses the theme of rebellion to develop the motif of creative burning and the severe torment associated with the process of creation itself. To ensure the internal movement of the novel about Frankenstein, Mary Shelley combines the myth with the motifs of the legends of Dr. Faust, the creation of the Golem, the biblical stories of Adam and the fall of Satan, as well as with their literary treatments, primarily Milton’s epic Paradise Lost.

The peculiarity of the philosophical atmosphere of the era was that the science-centered position was replaced by a new, romantic philosophy. All of this makes Mary Shelley’s novels quite peculiar, as they are largely related to scientific topics.

Like other romantics, Mary criticizes the theory of the omnipotence of the human mind, which cognizes the laws of nature in order to become its master, as well as the idea of the need to rebuild the world, the ability to penetrate the secrets of the universe and rationally explain everything in it. In the novel Frankenstein, the irony of life makes the human mind turn against itself.

Victor Frankenstein, like Prometheus, created a new life; however, the triumph of the human mind is not unquestionable. The scientist’s creation cannot find its place in human society, becomes violent and, like Cain, commits his «first» crime. The first victims of his destructive power are those who are particularly close to Frankenstein: his brother, best friend, and young wife. This is how the motif of destruction is woven into the creation myth from the very beginning.

By lifting the veil of secrecy, romantic heroes isolate themselves from the world of people (this motif is already characteristic of the late Enlightenment, for example, the novels of William Godwin). A researcher named Walton and Victor Frankenstein are guilty of abandoning their loved ones, simple human relationships, for the sake of their discoveries. The tragedy lies in the incompatibility between the limitless possibilities of man and the requirements and rules dictated by life in the real world and society, which leads to loneliness and despair. It is not the materialization of the scientist’s idea that is destructive, but the idea itself, which has no moral basis. Thus, in the novel Frankenstein, the theme of cognition, the thirst for a holistic explanation of the world and man, turns into a philosophical problem and an open polemic with the rationalist ideology of the Enlightenment. This controversy was an integral part of Romantic philosophy; it can also be interpreted as an awareness of the contradiction between theory and real life, which goes beyond theory.

This is not only about the image of scientists; Mary tells us that any idealistic scheme detached from life leads to tragic consequences. Therefore, on the other hand, she criticizes the idealism of her husband Percy Shelley. She believes that a person is unable to achieve an ideal, to realize a great idea in the material world and by material means. Walton cannot reach the pole because of the weakness of his sailors. Frankenstein’s creation cannot compare to God’s creation because the scientist creates it from disgusting pieces of dead matter. Consequently, the Demon’s sincere desire to win human affection also remains unreciprocated, as he is a grotesquely ugly material embodiment of a great idea. Everyone will be better off if people remain human. Mary Shelley acts as an enlightenment activist who seeks the unity of man and nature. But the question arises: what is human nature? And Shelley tries to answer this question by denying its individualistic nature. One of the main tragedies of the enlightened mind is its loneliness.

Social motives against enlightened individualism

The image of the Demon appears as an artistic embodiment of a whole range of philosophical ideas. In full accordance with the theories of the French Enlightenment and John Locke, the creature born as a result of Frankenstein’s experiments is a «Tabula rasa» (blank slate). Just like his creator and Robert Walton, the Demon himself strives for one thing: «cognition,» which always begins with cognition of itself. He cognizes the world through the simplest sensations (hunger, thirst, cold, loneliness) and reaches out to people, wanting to find warmth and love. However, it is not these simple sensations that define the character of the Demon, but rather a more complex sensory experience, that is, the social relations given to us in our senses. Here Mary Shelley seems to be telling us that human character is largely determined by society. It is the cruel attitude of the environment that generates hatred and a thirst for revenge in the Demon; the cause of evil lies not only in the very nature of the Demon as an individual. Thus, the theme of sinfulness and virtue turns out to be closely related to the theme of man in society and in solitude. The loneliness of the Demon in the novel is not psychological but social, in line with the philosophical tradition of William Godwin and Thomas Paine.

The theme of loneliness is perfectly emphasized by the story of the Demon’s spiritual development, which was determined by the three books he found in the forest. The motif is akin to a «robinsonade». Thus, from The Sufferings of Young Werther he learns about the experiences available to the human soul. Plutarch’s «Lives» help the Demon to look at people in a historical and social context. «Milton’s Paradise Lost is a metaphysical reality that encompasses the human world. Familiarity with this work prompts the Demon to compare himself to both Adam and Satan.

The motif of the unity of opposites plays a major role in understanding the relationship between Frankenstein and the Demon. Frankenstein and his creation are two sides of the same coin; they cannot exist without each other. The scientist and the creature he created are interdependent and clash in an insoluble contradiction. Initially, the Demon seems to be the personification of the dark side of Frankenstein’s soul, its symbol that has come to life. Gradually, Frankenstein identifies his creation more and more with himself, as evidenced by the fact that he takes responsibility for the deaths of his loved ones. Toward the end of the novel, the roles change: The demon begins to call himself the master of his creator. After Elizabeth’s death, the climax comes: Frankenstein finally forgets about the arrogance that put him alongside Prometheus. Like his own creation, he embarks on a path of rage and revenge. Creator and creation become inseparable, and in their common fall they are likened to Satan.

The gloomy atmosphere of Frankenstein makes Mary Shelley’s novel similar to Byron’s romantic poems and dramas, rather than Percy Shelley’s utopia. Frankenstein can be compared to Manfred: they do not deny the importance of reason and are thinkers who, despite the catastrophe, believe in progress and the victory of humanity over the unknown. In Mary Shelley’s novel, there is a motif similar to Byron’s 1821 novel Cain: the fate of the monster created by Frankenstein, who embodies all the injustice of the existing world, which turns good into evil. At the same time, Mary Shelley polemicizes with Byron: unlike Manfred and other characters of Byron, after a long and difficult journey, Frankenstein realizes before his death that it is a human duty to feel connected to humanity.

The motive of the disaster, science and egoism against nature

The theme of the duality between the «natural» and the «man-made,» which Shelley emphasizes, was very important for most Romantics and for philosophy in general. This theme affects such a feature of Romantic literature as the motif of catastrophe. This motif is of great importance and manifests itself in various spheres of scientific and cultural life, which is embodied in Shelley’s novel The Last Man.

As an example, we can consider the scientific work of Georges Cuvier, who in 1812 developed the theory of catastrophes, according to which changes in the living world occur under the influence of events that lead to the mass extinction of organisms. In the previous literary tradition, the motif of catastrophe was closely intertwined with images of nature and revolutionary change. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, European society had three main views on the relationship between nature and revolution. After the events of 1789, the revolution was likened to the renewing power of nature, and nature was perceived as a benevolent ally of the revolution, which needed a general renewal, after which a new, happy era would begin. This view was reflected in the creation of a new revolutionary calendar in France.

Later, after the disappointment with revolutionary terror, nature began to be perceived as a safe haven in which to relax from the stormy social life (supporters of this idea were, for example, François-René de Chateaubriand and his works Atala and René, and the late poetry of William Wordsworth). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the connection between nature and revolutionary transformations became a metaphor, and pictures of social utopias gave way to apocalyptic pictures of the collapse of empires and the dying of civilizations. Nature is no longer a safe haven, but becomes hostile to humans. In the 1800s and 1820s, a number of works of literature and painting appeared, the subjects of which were disasters or natural disasters (for example, de Granville’s novel Omegar and Siderea, Byron’s poem The Darkness, Thomas Campbell’s poem The Last Man, and Thomas Hood’s poetic short story of the same title).

In her novel The Last Man, Mary Shelley depicts the death of humanity at the end of the 21st century from a plague pandemic. As a rule, authors of the Romantic era break the previous tradition in which the death of people was a punishment for sins. For the Romantics, humanity’s movement toward death is causeless and inevitable. In Mary Shelley’s novel, the causes of the pandemic are also not specified. However, it can be assumed that there are at least two: the first (external) is the symbolic revenge of the East for the West’s desire to finally conquer it. Hadrian’s dreams of a brighter future for all people on earth are close to the enlightenment concept of universal equality, and an ironic reinterpretation of this concept is embodied in the motif of a deadly disease that equates all people in need. The second (internal) cause of the pandemic is the tragedy that occurred in Verneuil’s family. Mary Shelley used a technique common in the Romantic era: the desire to embody the inexhaustibility of an object (the universe and eternity) in a form that claimed to reproduce only its individual aspects. A misunderstanding between a young man and a young woman (Adrian and Evadne) becomes the «seed» from which a universal catastrophe grows.

The novel The Last Man, like Frankenstein, is romantic in its essence, but it contains a critique of romanticism. Mary Shelley destroys readers’ expectations by ironically rethinking the usual romantic categories and shows how untenable they are in the face of a global catastrophe.

Thus, the human imagination, which in Percy Shelley’s aesthetics appears as the greatest creative force, leads Mary Shelley’s characters only to deceptive illusions: throughout the novel, none of the characters’ hopes are destined to come true. Art turns out to be helpless — the characters of the books and the marble sculptures of Rome and the Vatican are unable to replace Lionel’s deceased loved ones. Nature, according to Mary Shelley, is also not kind to man. At the beginning of the novel, Cumberland’s pastoral descriptions only emphasize the wildness and ignorance of young Lionel and Loss (Lionel’s sister). With the outbreak of the pandemic, warm winters contribute to the spread of the disease, and the beauty of the landscapes, which embodies nature’s indifference to humanity, becomes an evil mockery of people.

The results of social progress are also unsuccessful. The society of the future in Mary Shelley’s novel, according to the theories of William Godwin and Percy Shelley, has come much closer to the ideal of reason. States still exist, but the English king voluntarily abdicates, class distinctions are largely resolved, poverty and disease are systematically eradicated, and, by all indications, the Golden Age is about to arrive. In describing the pandemic, Mary Shelley uses the same technique as Daniel Defoe in Diary of a Plague Year: she sets up an experiment to show how well a developed society can cope with a universal disaster. Like Defoe, Mary Shelley tells about many human destinies, unfolding many scenes in front of Verneuil (the story of Juliet, the story of Lucy, the story of an old peasant woman, the story of an army of marauders, etc.) Just as in Diary of a Plague Year, the novel shows the best and worst manifestations of human nature in the face of disaster.

However, unlike Defoe, Mary Shelley holds a pessimistic view of the possibilities of society, again converging with Byron’s position. The novel presents various variants of social organization: hereditary monarchy (represented by Adrian), the republican rule of Raymond, the democratic rule of Ryland, theocracy under the leadership of the false prophet, and anarchy embodied by looters from America and Ireland. In the face of the horrors of the pandemic, all forms of social organization are powerless.

None of the novel’s characters is destined to realize the romantic concept of human personality development, according to which the hero, moving to a new stage of development, acquires power. Verneuil, after meeting Adrian, becomes an educated and civilized man, but in the novel’s finale he has to return to the skills he acquired in his youth, when he was just a poor shepherd. Raymond is a hostage to his passions, and loses first his power and then his life. Adrian is able to use his strength and wisdom only when it is too late. Once again, reason is inferior to nature, as the failure of Victor Frankenstein had previously shown.

A spark of optimism amidst the gothic atmosphere

Many scholars call Frankenstein a Gothic novel because it contains supernatural elements. The supernatural aspect of the plot in the «Gothic» novel is important for refuting the former enlightenment ideal of Reason and remains only a preparatory step to understanding the complex interdependence of the rational and the emotional, the cognizability and unknowability of the laws of existence. In Mary Shelley, the theme of cognition of the world and man turns into a complex philosophical problem, a new concept of the world that was not present in either the Enlightenment or the Gothic novel. According to this concept, a person does not always achieve positive results in his or her actions, even if he or she is guided by reason and belongs to the «third» state of society. He is not a toy of supernatural forces, and his misfortunes are caused by his mistakes. Thus, the fate of the world depends on the mistakes of individuals who overestimate their own strengths and capabilities. At the same time, Mary Shelley uses the aesthetics of «gothic» novels in certain episodes of her works to create a tense atmosphere and attract the reader’s attention.

I would like to point out that Frankenstein is not based on science, but on metaphysics and the occult; Frankenstein strives not so much for scientific discovery as for alchemical immortality. Secondly, the novel shows how the human mind turns against itself in its quest to reach the heights of science and unravel the greatest mystery of nature. The power of the current is only a tool of the modern Prometheus, a way to revive the Monster, an impetus for the development of further conflict. In the novel The Last Man, the action is moved to the distant future. In this future, everything necessary for life is produced by machines, and people travel by aeronautics. However, these realities are only a background for the events taking place, and the life of the people of the imaginary twenty-first century is not particularly different from that of the contemporary writer. It follows that, although the novels contain elements of conventionality and fantastic plots, the fantastic nature of the novels is a feature of romantic aesthetics and is not so much scientific as mythological.

Of course, Mary Shelley was not a specialist in the exact sciences, but she, like Percy Shelley, read a lot and had an idea of advanced ideas and the latest theories. She herself claimed that one of the sources of inspiration for Frankenstein was Shelley’s and Byron’s conversations about the achievements of Erasmus Darwin and Luigi Galvani.

All of this makes Mary Shelley seem more pessimistic than Byron, but because of the open-ended ending in Frankenstein, readers can only guess at the fate of the Demon. The outcome of Verneuil’s efforts to find the survivors of the pandemic is also unknown. As a result, the world and human beings are understood as an unrealized possibility, something incomplete that emerges and is created continuously. Romanticism is characterized by the poetics of fragmentation and the ineffable, which may imply the presence of an open ending in a work. At the same time, Verneuil’s desire to sail to new shores (he is going to leave Europe and sail to Asia and Africa) is perceived as an attempt to unite the microcosm and macrocosm.

At the same time, when discussing the composition of The Last Man, its end and its beginning are combined: is Verneuil truly the Last Man, if one does read about him? The story told in Verneuil’s name is only a prophecy written on the leaves found in Sibyl’s cave. The function of the «Author’s Introduction» is to simultaneously «deconstruct» and «reconstruct» the existing world. This is manifested on two levels at once. On the one hand, Mary Shelley selects a part from the pile of leaves — what she considers necessary — and deciphers the writings, speculating and creating a coherent story. On the other hand, the story of the end of civilization that the reader is introduced to does not exclude the possibility of change for the better, as the origin of the text suggests that Verneuil’s story is a parable, a warning to humanity.

Reading Frankenstein and especially The Last Man, it is very evident that Mary Shelley is in dialogue with many writers, both past and present. Ancient myths, Homer, Aeschylus and Sophocles, the Bible, works of Renaissance and Enlightenment authors, classicists and the works of her contemporaries, especially William Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge, and the Gothic novel itself are important to Mary Shelley, as well as to most English authors of the Romantic era. The works of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, the poetry of Percy Shelley and Byron, as well as sources related to the natural sciences had a significant influence on her work. Thus, Mary Shelley deservedly takes her place among the most important figures of the English Romantic literary movement, not inferior to her husband and his equally famous friends. And her talent is not limited to the popular Frankenstein.

Добавить комментарий