History begins in the East

The Greeks themselves believed that philosophy, as well as other varieties of high culture, came from the more ancient and developed Middle East. It was considered very prestigious if you are connected with something more ancient, because as it is known “it was better before”, and veterans should be respected. The reason for this lies not only in the archaic view “ancient means good”, but also in the very genealogy of Greek civilization. The origin of philosophy in the East is by no means a mythologem of the Greeks. We already know the examples in Egypt and Babylonia; but the question of the importance of ancient Phoenicia in the genesis of Greek civilization is still very little touched upon, or rather underestimated and even depreciated, in historical science.

Of course, we know, and it is constantly said, that the Phoenicians before the Greeks monopolized navigation and began the colonization of the West; including, incidentally, the Phoenician colonization of Greece itself. We know that these colonies, as well as the “metropolis” of Phoenicia itself, were always located on the seashore and were commercial in character. All this applies equally to the Greeks, but the Phoenicians began their maritime expansion much earlier. In addition to what has already been said, the Phoenicians also had a state-city structure (by the way, this structure at an early stage of development had the cities of Babylonia, and for some time even in Egypt, and probably, in general, all over the world), again, earlier than the Greeks. Already here one would think that the influence on the Greeks must be undoubted; and as we shall see further on — it is even much deeper and stronger than it is usually considered.

This “Phoenician question” is not emphasized much, if only because all of the above is considered to be the reason for the unique development of Greece. Considering Phoenicia itself from this point of view, as it were, forces us to conclude that the reasons for the success of the Greeks are different from the generally accepted ones. Such an approach forces us to take all the overlapping places out of the brackets of our equation. And this deprives us of most of the usual and very reasonable explanations. And then in our investigation of the “phenomenon of the Greeks” we lose the trail, we are left almost empty-handed, which is extremely inconvenient.

But one could go the other way, and insist that the Greeks’ explanations of success still work properly; in that case, the Phoenicians must have at least started down the same path that the Greeks started a little later. And if Phoenicia had rich trading and maritime polities, had alphabetic writing, etc., which is certain — where is their high culture? Where are their philosophers? Why do we know so little about the Phoenicians? I will not answer these questions, as I myself do not know the final answer to them; there is very little information about the Phoenicians.

We know that even in their heyday they were monarchical and oligarchic states with a large property stratification. The degree of their proximity to ancient civilizations, which set the tone of social life in the entire eastern region, is of no small importance in explaining the failure of the Phoenicians. Such proximity rather inhibited cultural development. We can only hope for future archaeological discoveries that we will find at least a few authentic Phoenician literary works. On the basis of what is available now, little can be said for certain. In my opinion, however, it seems to me that all evidence points to the Phoenicians having a very advanced culture (if only because of the probable influence of Minoan Crete), ahead of Egypt and Babylonia, or at least not inferior to them.

In this article I only want to briefly characterize the circumstantial evidence for Greek-Phoenician connections, without regard to exactly how advanced the culture of the Phoenicians was.

“Phoenician” myths

The most interesting for us are the legendary characters that Greek mythology itself associated with its origins. Phoenicia’s own history, religion and mythology are a second order matter, given their fragmentary nature and lack of a prescribed connection with the Greeks. The Greeks, however, see the matter this way. The king of Tyre and Sidon (the largest cities of the Phoenicians) named Agenor was the son of Libya, the daughter of the king of Egypt named Epaphus (and the son of Zeus from Io). Thus the Phoenicians are painted as “grandsons of the Egyptians and children of Africa”. Agenor’s father was the sea god Poseidon himself, from whom Livia gave birth to a second child, Agenor’s twin named Bel. Bel later became king of Egypt, like his grandfather Epaphus. The whole myth is one continuous reference, speaking of the Egyptian origin of Phoenicia and Greece. This Agenor had many children, but for Greek mythology the most famous and significant were Cadmus and Europa.

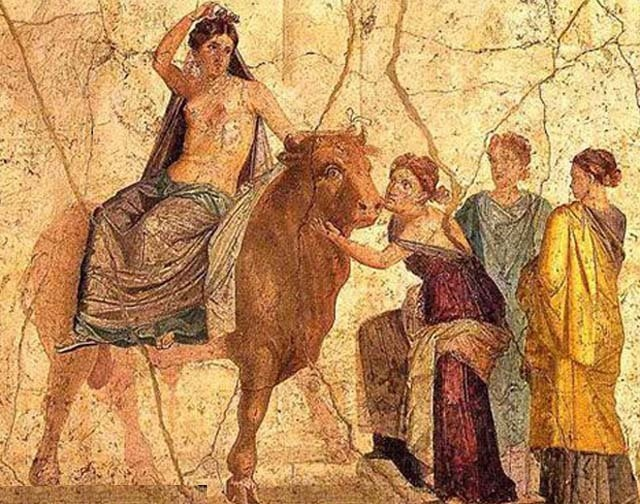

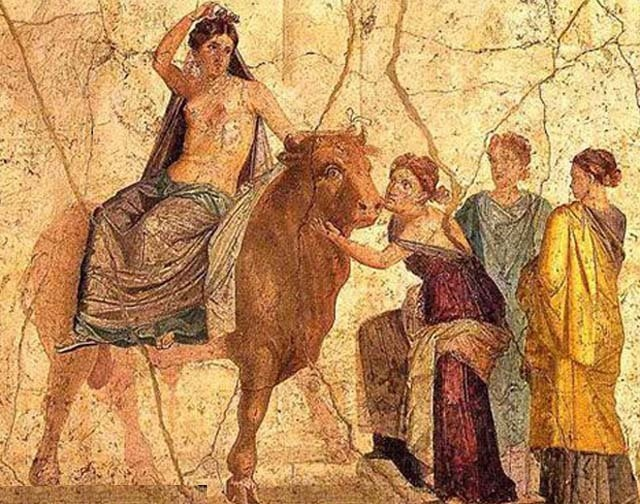

Once Zeus having turned into a bull kidnapped Europa, who liked him, and lay with her on the island of Crete, where she remained to live further, becoming the mother of Minos, Radamanthus and Sarpedon. As a whole, her destiny has developed even well, in fact it has taken in a wife the tsar of Crete, and as there were no children from this marriage, the further governors of island became descendants of Zeus and Europe. However, Phoenician relatives knew nothing about it, so worried Agenor sent four of her brothers in search of his daughter, forbidding them to return home without their sister.

The brothers, by the way, never found her, but in the process of searching they traveled all over Greece.

After an unsuccessful search, the chief of Agenor’s sons, the Phoenician Cadmus, was forced to settle in Greece. Legend attributes to him the founding of the city of Thebes in Boeotia (where Europa was also honored). In his wanderings Cadmus also visited Rhodes, also bearing traces of Phoenician colonization, where he offered sacrifice to Athena Lindia. “The Arabs who crossed with Cadmus» settled on the island of Euboea, which is also interesting, because it is the same island from which the history of Greek colonization will begin, the location of the famous trading polities of Chalcis and Eretria.

The Greeks associated the advent of the Copper Age with the appearance of Cadmus; he is also the legendary inventor of Hellenic writing (historical fact, the Phoenicians brought the alphabet to the Greeks). Sailing from the East to Greece, he stopped on the island of Santorini (Thera, Fira) and left some of his companions there. Later, Teras (Thera) arrived on this island, after whom the island was named. This island is known today as the brightest place of preservation of cultural monuments of the Minoan civilization. It is here, on Teras, the oldest (XVIII century BC) Greek writings were found. And recently (in 2003) a letter from the king of the state of Ahhiyawa (that is, apparently, the Mycenaean power) to the king Hattusilis III (c. 1250 BC) was found. This Greek king mentions that his ancestor Cadmus had given away his daughter to the king of Assouba, and certain islands came under the control of Ahijava. The king of the Hittites responded by claiming that the islands belonged to him. This conflict over the Asia Minor coast chronologically coincides with the dating of the Trojan War. And if this is so, the Achaeans directly derived their descent from the Phoenician Cadmus.

In general, the role of the figure of Cadmus for the Greeks cannot be overestimated. Cadmus was not the only one who went in search of Europe and continued to live outside of Phoenicia. Having made sure that it was impossible to find his sister, his brothers settled in different countries, founding other royal dynasties.

The first of the brothers (Thasos) settled in Thrace, founding there the city of Thasos on the island of the same name (the colonization of this area is historically confirmed, there is also the Phoenician colony of Abdera nearby). Another brother of Cadmus, Phoenix , is the founder of “Phoenicia” (a certain united Phoenician kingdom); according to another version, he went to Africa and stayed there, which is why Africans are called Punyans (mythological explanation of the colonization of Carthage). Cilicus, in the manner of his brother Thasos, called the land he conquered Cilicia. Earlier its inhabitants were called Hypacheans. According to the later philosopher Eugemerus (a fan of “grounding” myths), this is the ruler of Cilicia, defeated by Zeus. Sometimes his children are called Phasos and Thebes (a reference to Thebes?).

So there is a brother and a sister, both Phoenicians, and both of extraordinary importance to the genealogy of the Greeks. Cadmus is the ancestor of the Achaean kings, and Thebes is one of the most important cities of antiquity. Europa is the queen of Crete, the mother of the first of the most powerful “Greek” kings. The Minoans and Mycenaeans, as we know, were in conflict; but for later Greeks, they are almost one culture, their great past, and both appear to be linked to Phoenicia.

Now, for completeness of the context, let’s go a little on the “line of Europe”. One of the sons of Zeus and Europa was Rhadamanthus, who was famous for his justice, as it was he who, according to legends, gave the Cretans laws. At some point, he probably killed his brother (Minos), for which he was banished from the state. While in exile, Rhadamanthus settled in Ocalea in Boeotia (near Thebes, which is obviously not accidental) and married Alkmena, the mother of Heracles (already the widow of Amphitryon). The name of Rhadamanthus became nominal as a strict judge. So it is not surprising that after his death he, as a reward for his justice, became, along with Minos and Eak, a judge in the afterlife (according to another version — on the “Islands of the Blessed” together with the titan Kronos). His instructions were set forth in Hesiod’s poem “Great Works” (by the way, Hesiod came from Boeotia, and Phoenician roots are not excluded). Later Hellenistic rationalization of myths already stated that there was a historical ancient Rhadamanthus, who first united the cities of Crete and civilized it, established laws, claiming that he received them from Zeus. And Minos, who ruled later, only imitated Rhadamanthus.

The story of Heracles’ mother is also not accidental, because the kings of Sparta traced their ancestry back to him, and the Spartans themselves believed that they owed their laws to Crete (so we see here a triangle of Crete-Sparta-Thebes). Later, archaeologists found recorded laws on Crete, but not from the Minoan period — and those actually turned out to be similar to the Spartan laws. The philosopher Socrates, according to Plato, considered these laws to be the best, and put Sparta and Crete on the same level in this matter. So, perhaps it is not accidental that the Spartans did not want to build walls, as it was accepted long before them in the Minoan civilization.

King Minos is the most famous of the sons of Europa — he is the legendary founder of the Minoan civilization and the father of “thalassocracy” (maritime hegemony, as Samos or Athens would later be). He is father to Androgeus, Deucalion, Glaucus, Catreus, Eurymedon, etc.

Minos drove the Carians out of the Cyclades and established colonies there, placing his sons as rulers, and succeeded in capturing Megara and extending power to the mainland. When his son Androgeus was murdered in Athens, Minos forced King Aegeus to pay tribute, 7 young men and 7 maidens every year, or every nine years. It was believed that these captives were condemned to be eaten by the Minotaur who lived in the Labyrinth. This lasted until the hero Theseus (son of King Aegeus) killed the Minotaur. Archaeology has confirmed that the palaces of the Cretans were built with a labyrinth-like layout; and not only was the Bull their religious symbol, but there were traces of ritual cannibalism of children.

Subsequently, the great-grandson of Europe and grandson of Minos — Idomeneus, will be one of the main allies of Agamemnon and Menelaus in the campaign against Troy, and put up one of the most significant flotillas. It turns out that even in Trojan times — Crete is one of the strongest parts of Greece. But all these ruling dynasties raise themselves to the Phoenicians, and according to mythology it was the Phoenicians who showed the Cretans the beauty of the state system, established laws (the good for which the Greeks later called even mediocre fools “Sages”), and the Greek alphabet was quite consciously raised by the Greeks themselves to the Phoenicians.

Phoenician pre-philosophy

Diogenes of Laertes has a lengthy mention that philosophy could theoretically have arisen much earlier in the East. He himself, however, does not think so, for he feels contempt for barbarians; but he says about the existence of Eastern doctrines that were older than Greek ones (not worthy of the name of philosophy, apparently), and he himself trusts this information. The general picture is approximately as follows:

“… the Persians had magicians, the Babylonians and Assyrians had Chaldeans, the Indians had Himosophists, the Celts and Gauls had the so-called Druids and Semnotheans (Aristotle [probably his student] writes about this in his book On Magic and Sotion in Book XXIII of the Successions); the Phoenician was Oh, the Thracian was Zamolxis, the Libyan was Atlanteus.”

Mochus of Sidon was an ancient Phoenician philosopher from Sidon, who lived at the end of the 2nd millennium B.C. The exact time of Moh’s life is unknown, Greek authors usually define it as “the era of the Trojan War”; but this is most likely just one of the synonyms for the phrase “long ago”. Only the recognition of Mochus as the oldest of the Phoenician sages is certain — Diogenes of Laertes calls him a proto-philosopher, placing him next to the legendary Atlantean.

Mochus was an astronomer and historian (as were members of the Greek school in Miletus), but is best known as a “physiologist,” that is, a researcher into the nature of things (the main theme of all early Greek philosophers). Moss formulated his own conception of the creation of the world, according to which the “primary elements” were Aether and Air. He also believed that, like language, which consists of letters, the world also consists of indivisible particles, thus becoming the “father” of the atomistic theory, later revised in different versions by Pythagoras and Democritus.

In addition to these achievements, Mochus is considered the founder of a philosophical school, the first in his time, which included Chalcolus and Darda, mentioned in the Bible. According to the late antique philosopher Yamvlichus, Pythagoras also communicated with representatives of the school of Mochus, which means that it continued to exist at the same time as the school in Miletus. Unless, of course, all this is not one continuous modernization of late antique authors, which is very, very likely.

Mochus is mentioned in his works by Strabo, Josephus Flavius, Sextus Empiricus, Diogenes of Laertes, Tatian, Eusebius of Caesarea, and Suda; i.e., this is by no means an isolated mention, although all of them probably simply depend on the Stoic Posidonius, who first mentioned the Phoenician from the sources available to us, and he did so probably because Posidonius himself came from the same Sidon.

The “Libyan” Atlante, not a titan but the first king of Atlantis, is also associated with Phoenicia. He was the son of Poseidon and the mortal woman Cleito. Similar versions are found in the works of Eusebius and Diodorus; in these accounts Atlanteus’ father was Uranus and his mother was Gaia. His grandfather was Elium “king of Phoenicia” (this was the name by which the Phoenicians called the Most High God), who lived in Byblos with his wife Berut (a hypostasis of Baal). Here Atlanteus was raised by his sister, Basilia (the legendary first queen of Atlantis). Most of the information about the thought tradition of the Phoenicians has come down through the text of an ancient Phoenician author from Beirut named Sanhuniaton, who lived, according to Eusebius, “when Semiramis was queen of Assyria”.

In three books he expounded the main points of the Phoenician religion, which he drew from the columns of the sacred temples before they were perverted by the priests of later ages. The content of his work in Phoenician was transmitted in Greek by Philo of Byblos in his History of Phoenicia, fragments of which are quoted by the church historian Eusebius in his Chronicle. In particular, Eusebius cites Sanhuniaton as evidence that most pagan gods were based on real historical figures. It turns out that already in those times Phoenician historians were grounding mythology and engaging in rationalistic interpretations.

In Sankhuniaton’s account all titans, including Cronus, come from Phoenicia, and they, the titans, founded it themselves. This surprisingly lies on the Greek legends about the war of gods and titans, for then we get a version of the interpretation of the myth, where the gods (Greeks) are children of titans (Phoenicians), against whom they soon rebelled and defeated their fathers in the struggle (maybe an illustration of conflicts for colonies?). The most important thing for us is that this Phoenician writer also existed before Greek philosophy, and if Moh’s atomism can be deduced from his texts (and this is theoretically, with a stretch, possible) — then Greek philosophy loses a lot of its originality. Although it is always possible, of course, to doubt the authenticity of Sankhuniaton’s texts and all the testimonies about Moha, and to see in them the modernization of the Hellenistic era.

“These Phoenicians, who came to Hellas with Cadmus, settled in the land and brought to the Hellenes many sciences and arts and, among other things, a written language, previously, I believe, unknown to the Hellenes.” (c) Herodotus

In addition to the Phoenicians, Diogenes of Laertes mentions the sage Zamolxis, the main deity of the Thracian cult. The most characteristic elements of the cult of Zamolxis (andreon and feasts, occultation in the “underground dwelling” and epiphany after four years, the “acquisition of immortality” of the soul and the doctrine of a happy life in the afterlife) bring it closer to Greek mystery. It was from Thrace that came the Greek cults of Dionysus, associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries, so prevalent among conservative rural farmers, and generally recognized as having influenced the philosophy of Pythagoras. According to Strabo, Zamolxis himself was a slave of Pythagoras, from whom he learned “certain celestial sciences.” It was also believed that Zamolxis (like Pythagoras) traveled to Egypt, then known as the land of magicians, and learned “some things” from the Egyptians. Back in his homeland, Zamolxis managed to convince a ruler to take him on as an advisor (much like the Pythagoreans convinced rulers in Italy) because of his ability to communicate the wishes of the gods. At first Zamolxis was a priest of the most revered god of the Dacians, but later he succeeded in getting himself honored as a god (which also reminds us of Pythagoras).

In the dialog “Charmides,” Socrates describes his meeting with one of the herbalists of “the Thracian ruler Zamolxis, who possessed the skill of conferring immortality,” and reports:

«This Thracian physician narrated what he had learned from his ruler, who was a god. Zamolxis, the physician reported, taught that one should not treat the eyes without curing the head, and the head without paying attention to the body, and the body without making the soul well. Therefore, concluded the Thracian healer, the remedy for many diseases is unknown to Greek healers, because they do not pay attention to the body as a whole.»

And even this maxim strongly resembles the philosophy of Pythagoras and Pythagorean physicians such as Alcmaeon.

I will not go into more details, but it is obvious that Egypt and Babylon had a direct influence on (->) Phoenicia, which itself had an influence (->) on Greece. All early Greek wisdom is just repeating what had already existed centuries before them, there is virtually nothing new there. The first worldview revolution took place around 900-700 BC in Babylonia and Phoenicia, the Greeks had already adopted it in a ready form around 650-600 in the person of the same Thales. All Greek historians almost unanimously attribute the invention of geometry to Egyptian surveyors (from where Pythagoras’ voyage to Egypt came), but they immediately separated geometry and theoretical mathematics, and also separately distinguished astronomy.

Thus, mathematics was attributed to the Phoenicians, and astronomy to the Chaldeans (Babylon). But later Hellenistic historians considered the practical origin of all sciences to be a more reasonable explanation. Therefore, for them the development of astronomy by the Phoenicians looked much more logical, since they surpassed everyone in navigation to such an extent that they sailed at night in the open sea, and for this they needed developed astronomy (unlike mainland Babylon).

If all this is true, then the development of astronomy and mathematics (here the argument also went through the practical need of traders in bookkeeping) should coincide with the heyday of Phoenician colonization, and this is 900-700 BC, and here also lies another argument. After the Macedonian conquest of Persia — Greek scholars had access to many temple archives, and they compiled a regular calendar of lunar and solar eclipses (what so progressed Thales of Miletus). The calendar starts around 760, arguing that the Babylonians began regular accounting only from that time (in fact, such things could have been done much earlier). Thales made his eclipse prediction in 585, just a century and a half later. Also, it was Thales who was considered the founder of Greek mathematics, and it was only later that the young man Pythagoras learned from him.

But the most interesting thing is not even this, but the fact that the ancient tradition itself considered Thales a Phoenician by blood, and Pythagoras, who studied under him, was also a descendant of Phoenician merchants, and even the more generally recognized teacher of Pythagoras, the poet Pherekides, was also considered, if not a Phoenician, then a man who “got his wisdom from the secret Phoenician books”. As mentioned above, Thebes (Boeotia) was proud of its Phoenician mythological history, but it was from Boeotia that the poets Hesiod and Linus originated. Here is what Diodorus of Sicily wrote about Linus:

«It is said that Linus was the first of the Hellenes to discover the laws of rhythm and singing, as well as to apply for the first time to Hellenic speech the special scripts brought by Cadmus from Phoenicia, while establishing the name and defining the lettering for each sign. These letters are commonly called Phoenician, because the Hellenes borrowed them from the Phoenicians … Linus reached extraordinary heights in the field of poetry and melody, he had many pupils”.

The remnants of Linus’ writings fit very well into the cultural context of Thales and Pherekides, and even go beyond them, even touching on the philosophy of Parmenides. Other legendary hero-poets, Orpheus and Museus, were considered contemporaries of Linus (incidentally, this is around 900-800 BCE, just when the Phoenician cultural upheaval began), and they also have passages highly reminiscent of Parmenides’ philosophy (which greatly devalues his innovation). As mentioned above, even atomism may have been invented in Phoenicia, though this is no great tragedy for Democritus, for before him atomism was actually preached by Pythagoras as well. But as in the case of Moh of Sidon — all this can be safely denied, seeing here late antique insertions and modernization.

The other eastern influences

We have only to mention Diogenes of Laertes’ excerpts on the philosophy of Egypt, Persia and India to finish our cursory review of the pre-philosophy of the East: «The hymnosophists and druids spoke in mysterious sayings, taught to honor the gods, to do no evil and to exercise courage; the hymnosophists even despised death, as Clitarchus testifies in Book XII. Nothing special, except a slight hint at the importance of ethics and, perhaps (but not fact), a philosophical solution to the problem of death, which is considered an achievement of early Hellenism. And here we see practically Stoicism in embryo.

«The Chaldeans practiced astronomy and divination. The magi spent their time in the service of the gods, sacrifices and prayers, believing that the gods listen only to them; speculated about the essence and origin of the gods, considering fire, earth and water as gods; rejected images of the gods, especially the distinction between male and female gods. They composed works on justice, asserted that to give the dead to fire — unholy, and cohabit with mother or daughter — not unholy (so writes Sotion in Book XXIII), engaged in divination, divination and asserted that the gods are to them in person, and in general, the air is full of visions [mystical theory of Democritus], the flow or soaring of which is discernible to the keen eye. They did not wear gold and jewelry, their clothes were white, their bed served them the earth, food — vegetables, cheese and coarse bread, staff — a reed; with a reed they pierced and brought to the mouth pieces of cheese at meals. They did not practise sorcery, as Aristotle testifies in “On Magic” and Dion in Book V of the “History”; the latter adds that, judging from the name, Zoroaster was a star-worshiper, and in this Hermodorus agrees with him. Aristotle, in Book I of “On Philosophy,” holds that the Magi are more ancient than the Egyptians, that they recognize two primordials, a good demon and an evil demon, and that the former are called Zeus and Oromazd, and the latter Hades and Ahriman; Hermippus (in Book I of “On the Magi”), Eudoxus (in “A Tour of the Earth”) and Theopompus (in Book VIII of “The History of Philip”) also agree with this, and the latter adds that, according to the teachings of the Magi, people will rise from the dead, will become immortal and that only by the spells of the Magi and the creature is kept alive; the same thing is told by Eudemus of Rhodes. And Hecataeus informs us that the gods themselves, in their opinion, had a beginning. Clearchus of Sol in his book “On Education” considers the Gymnosophists to be disciples of the magicians, and others raise even the Jews to the magicians”.

Here already very striking is the knowledge of all the above-mentioned Greeks that Persian and Indian philosophy have the same roots (Vedic religion), and strangely enough, they consider the Indian offshoot as later, or less “orthodox” from the point of view of the Proto-Indo-Iranian religion. It is not difficult to see that this description alone is worth more than what the Greeks themselves enthusiastically tell us about their “seven sages.” But the Persian “magicians” are not inferior to the Egyptian priests.

«The Egyptians in their philosophy reasoned about the gods and about justice. They maintained that the beginning of all things is substance, from it are distinguished the four elements , and in completion are all kinds of living beings. They consider the sun and the moon as gods, the first under the name of Osiris, the second under the name of Isis, and the beetle, the serpent, the kite and other animals serve as allusions to them (so say Manephon in “A Brief Natural History” and Hecateus in Book I of “On Egyptian Philosophy”), to which the Egyptians and erect idols and temples, because they do not know the appearance of the god. They believe that the world is spherical, that it is born and mortal; that thestars consist of fire , and this fire, moderating, gives life to everything that is on earth; that eclipses of the moon come from the fact that the moon falls into the shadow of the earth; that the soul outlives its body and moves into others; that rain is obtained from transformed air; these and other of their doctrines about nature are reported by Hecataeus and Aristagoras. And in their concern for justice they have established laws at their place and attributed them to Hermes himself. They consider animals useful to man as gods; it is also said that they invented geometry, astronomy and arithmetic. This is what is known about the discovery of philosophy.»

So Linus, Hesiod, the philosophers of Miletus, Pherecydes and Pythagoras all belong to plus or minus one tradition, the roots of which are partly in the Phoenicians and partly in Egypt and Babylonia, if we are to believe the doxography. As time goes on, the version of eastern influence finds more and more confirmation, and hopefully all these strings will still be tied together at some point on the basis of more convincing sources than we have now.

What does all this mean?

At least, all the early Greek wisdom (the so-called pre-Socratics) — only repeats the already existing before them for centuries, there is almost nothing new. But, in any case, in defense of the Greeks we can say that their lag is minimal. And since there are no names left from the Eastern sages, nothing has changed for us in fact; our heroes are still heroes, just deprived of the title of discoverers.

Heraclitus is striking and stands somewhat apart. The East was too focused on the Whole, on unity; so were the ancient Greek sages. But Heraclitus outlined a conceptual breakthrough (although in a general sense he also shared the concept of the Whole), and in this case, Parmenides’ reaction to him is nothing more than an archaic attempt to “return to the roots”. A separate achievement is the effect of scale. The wisdom of the Near East and Greece is one, but in the East the sages perceived it as a whole, while in Greece this unified “wisdom” was broken into parts and cultivated by “schools”. As a result, there was a total concretization of essentially the same material (Empedocles, Anaxagoras). And when all this mountain of additions tried to cover again as a whole, somehow to systematize — there appeared encyclopedic doctrines (Sophists, Democritus, Aristotle), which had never existed before. Such emergence of separate schools and new systems occurred synchronously with the Greeks in India and China, but the Greeks, nevertheless, were able to go further than their competitors, and this phenomenon still requires clarification of the reasons.

The futility of trying to go further in the knowledge of physical and logical theories leads to a focus on ethics. In fact, the primacy of the Greeks in this area is also called into question. There is evidence that well-developed ethical systems could have existed in pre-Socratic times, or even earlier (if we take into account the “teachings” of the Old Kingdom, etc.). To a great extent this question also depends on the decision about the historical dating of the book of Ecclesiastes and the book of Job. But, in any case, “Eastern Ethics”, even in its most radical version, is still more conservative than Hellenistic ethics, so we can say that the Greeks are still innovators in this matter.

Besides, it is the division of the “whole” wisdom into parts, and the subsequent view of the “whole” from the parts’ side, that sets a quite unique specificity. From a purely formal point of view, even the teachings of the Stoics and Epicureans do not differ much, and sometimes even coincide verbatim. But precisely because of the different starting points, in fact, the “same thing” in its form, and subject matter, leads to quite different worldviews. Such elaborate detail and subtlety of difference clearly could not have been available to philosophers in the pre-Socratic era.

And yet, the picture of early Greek philosophy is seriously altered. It changes seriously, even if we want to consider the history of Greek philosophy in isolation from the world context, in and of itself. And this is what we will try to talk about in the following essays.

Добавить комментарий