After the above-mentioned five semi-mythical characters and poets of the “Cyclic” — follows the epoch of the “sages” (which, by the way, is very funny, because the word “philosopher” means a lover of wisdom, and “sage” therefore stands above “philosopher”). But the same “Cyclic” poets had other lyricist contemporaries, so before I go on to the “sages,” I will not overlook these men. Some of the early poets were direct contemporaries of the later Nine Lyrics and Seven Wise Men, but these two groups will be separated into separate sections, and we will begin with the lyricists who were contemporaries of Cyclic poets.

Lyric poetry

Of the elegiac poets known to us, Callinus of Ephesus (ca. 685-630) is considered one of the oldest. The only thing that has survived from his work is the call to defend the homeland, specifically the defense of “land, children and wife”, as well as another rather archaic in meaning poem, retold in prose by us in this way:

«You can’t escape fate, and often the fate of death befalls a man who has fled from the battlefield. No one pities the coward, no one honors him; the hero, on the contrary, is mourned by the whole nation, and during his lifetime they honor him as a deity”.

The same theme sounds no less vividly in the elegies of the Spartan poet Tirtheus (note 665-610), who encouraged the Spartan soldiers in their war with Messenia. Tirtheus ridicules cowards and fugitives in the same way; but it is interesting that when he lists heroic qualities, using the best heroes from the epic as examples, he finds them insufficient.

Pride will serve both for the city and the people

He who, stepping wide, will advance to the first rank

And, full of perseverance, will forget the shameful flight,

and his life and his mighty soul.

To die in the first ranks for his native city — this is the supreme feat, and the main quality of the hero. The elegies of Tirtheus also contained an exposition of the foundations of the Spartan state system; they contain praise of Spartan institutions, myths sanctifying the structure of the Spartan community, and appeals to preserve the “good order”. Not surprisingly, these elegies were sung by Spartans even hundreds of years after the author’s death. Tirteus is Lycurgus in verse. But Tirteus himself did not write in the Doric language of the Spartans; he wrote in the Ionian dialect, which was the only acceptable language for the poetry of all Greeks at that time.

The poetry of Archilochus (ca. 680-630) is more personal and subjective against their background, although it is presented from the same conservative primitivism; he praises his personal life, his military adventures, and his attitude toward friends and enemies. Archilochus lived a life of war, for he lived in a time of constant warfare of his native island against the Thracian tribes, and most likely for this reason he honored Ares as his god. However, despite all this, he treats the tradition somewhat ironically. Thus, for example, Archilochus writes about his exploits in the high-pitched Homeric style, but in the same style he suddenly tells about how in his flight he had to throw his shield (an unforgivable impertinence within the framework of aristocratic ethics).

In addition, he is considered the founder of the literary iambic, which originated from folk “songs of denunciation” and within which one could pour out invective and mock one’s opponents (cf. battle rap). Archilochus even prided himself on his ability to repay evil for wrongs done to him. He can safely be called the first “battle-rap” in poetry; for example, the girl who refused to marry him, he calmly denounced with epithets whore. But what is much more interesting from the ideological point of view — Archilochus already posed the problem of the changeability of existence, in which everything depends on “fate and chance” (and where are the Gods?), at the same time, he recognizes the importance of human effort. This is already a significant worldview shift; and it is worth noting separately how much Archilochus is in tune with the philosopher Heraclitus, long before he was born.

The poet Semonides of Amorg, a contemporary of Archilochus (and with him Tirtheus and Callinus), went even further along the path of developing these conventional-progressive features. His didactic poems are dominated by pessimistic reflections on the deceitfulness of human hopes, on the threats hanging over man: old age, disease and death. In the divine management of the world he sees nothing but arbitrariness. The conclusion of all this is to enjoy the benefits of life as long as possible. Along with this, a primitive and patriarchal trolling of women can be found with him, where he categorizes female characters by comparing them to different animals, and thus deducing the very origin of women, as a human species, from different animals. Semonides therefore “went further” very conventionally, and the reasons for this are very pessimistic and “negative”. He has come to criticize tradition only because tradition is no longer good enough for his conservative spirit. But, philosophically speaking, even in this cynicism about women, one cannot help but notice that in his mind it is quite permissible for man to have descended from animals, by, we must suppose, some evolutionary change. We will not say this for sure, but there is nothing impossible in such evolutionism, because only in some 50-60 years evolutionary ideas will already be set forth in the philosophy of Anaximander of Miletus.

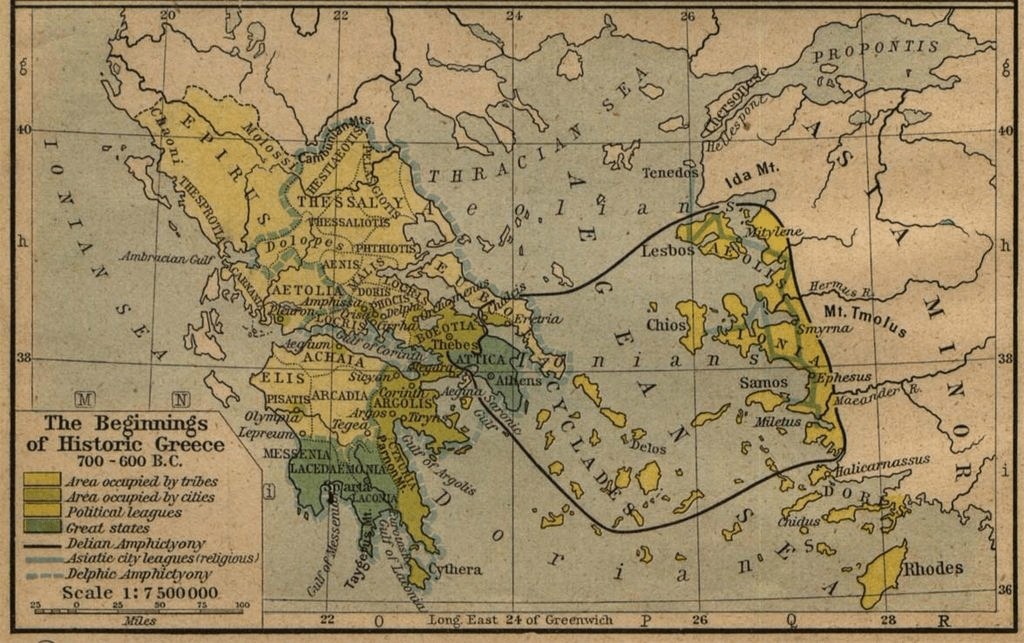

The motifs of pleasure are further developed in the next generation, for example in the Ionian Mimnermus (ca. 635-570), whom the Greeks considered the first poet of love. He is a contemporary of Sappho and of the early “nine,” but little is preserved of him, and we only know that he preached meditations on the transience of life and the importance of pleasure; and that legend reduces him to one of the “seven sages.” The story goes that, it is said that when Mimnermus wrote that a life of sixty years, unmarred by disease and problems, would be considered ideally lived, the sage Solon replied to him that it was better to replace sixty with eighty (certainly wise, but we would say even better with a century). We also know that Mimnerm wrote a poem about the founding of the city of Smyrna, and about the struggle of this city against the Lydian kingdom, which once again proves how easily hedonism can be combined with “high”, in this case with patriotism and historical, paramilitary themes.

The Nine Lyricists

As forerunners of the “philosophical turn”, we shall begin, perhaps, with the “lyricists”. The above-mentioned Cyclic epic, together with the classical epic, were the basis not only for painting and theater of the classical era, but also for the lyric genre of poetry, and, in principle, for all Greek art taken as a whole. Under this collective name “The Nine Lyricists”, we have reached a canon, i.e. a collection of authors recognized as the best among the lyric poets of ancient Greece, which was put forward by philologists in Hellenistic Alexandria as a worthy model for critical study. Only four of them concern the pre-philosophical era, and specifically in this article we will only touch upon them (the others for later).

The first “pre-philosophical” four contemporaries of Thales include: Alcman, Sappho, Alcaeus and Stesichorus.

The remaining five include Ivicus, Anacreontes, Simonides, Pindar, and Bacchylides.

So far our reviews have listed about 25 names, each of which for the Greeks was on a par with Pythagoras, and in some cases could be quoted even more highly. With all this material both the “Sages” and the “Lyricists” were well acquainted; it was the intellectual foundation for all of them. Of course there were few more significant names; even in the same field of poetry, a dozen more names of importance to the Greeks could be added. On top of this could be superimposed as many as twenty names of various great politicians, whom the Greeks honored even much later, even in Plato’s time; and this is not even counting the sculptors, architects, and musicians known by name. But if from all this mass of names, which every educated Greek had to know (Thales, for example), to sift out the unimportant ones, there would still be a dozen names, from which consisted the minimum foundation of knowledge for the new generation of sages. And for the philosophical generation itself, i.e. the generation of Pythagoras, our “seven sages” and at least four of the lyricists are added to this impressive list.

All this I bring only for the modest purpose that when studying ancient philosophy and art, the reader should realize the scale. In the history of philosophy, it is customary to “start with Thales,” but in fact there is much more behind him than Homer’s mythology alone.

Alcman and Stesichorus — the foundation of future tragedians

First among the “nine” chronologically is Alcman (2nd half of the 7th century B.C.), who was almost certainly descended from slave parents; he most likely came from Sardis, the capital of Lydia. Alcman is the first poet known from surviving fragments to have written songs for chorus. But, oddly enough, he lived and worked in Sparta in the period after the 2nd Messenian War. In Sparta, where Apollo and the virgin goddess Artemis were particularly revered — maiden choirs were especially common. For them, in addition to texts, Alkman created melodies and developed dance movements. He wrote mainly paeans (hymns to the gods), proomia (introductions to epic recitations) and parthenia (songs for female chorus). It was in Sparta, where Alcman was deeply revered for several centuries, that a monument was erected to him. The text of one of his songs has come down to us; it is composed of separate parts linked by formulas that define the end of one story and the beginning of another:

- Glorification of the ancient heroes of Sparta, the brothers Dioscurus, then the sons of Hippocoontes, slain by Heracles;

- Reflections on the power of the gods and the frailty of human life, and the moral precepts derived therefrom;

- Glorification of the chorus itself, which performed the Parthenios, its leader, and the individual members who performed the dance.

From the largest surviving passage we learn a few secondary-playing but interesting details:

«All of them, brave ones, my song will not forget. Fate and Poros (wealth) have broken those men, — the oldest among the gods. Effort is in vain.»

Or another motif: “Blessed is he who spends his days with a cheerful spirit, knowing no tears”.

Of course, we have seen similar motifs before in Archilochus, Semonides, and Mimnermus (the latter, by the way, crossed paths with Alkman for forty years of his life); but still, don’t these words look like something out of post-classical antiquity? Isn’t this “decadent Hellenism”? And yet, against the background of the gods, even the greatest mortals are mere “nothing,” and this archaic thought, dominates in various forms throughout Alkman’s writings. Man is not the center of his plots, and it is probable that nothing depends on the will of the mortal. Nor does Alckmann bypass Homer’s plots, and he certainly does not bypass the “Trojan War” with its mythological characters. Moreover, in all “nine” taken as a whole, these motifs are found more often than in the early lyricists (who, importantly, still alive caught the Cyclic poets). This is most likely due to the fact that the wretched “Alexandrian criticism” chose these authors as the “nine”, and mainly because they wrote on the motifs of Homer, the favorite of all these critics, and not because they wrote really well.

But still it is worth recognizing that although he lives in Sparta, but his worldview almost does not stand out in its conservatism from the average representations of the ancient Greek, from the same Hesiod or Cyclic poets. And of the distinctly good sides we may single out his philosophical views, the very fact of their existence. As we have already seen in the lines above, Poros (wealth) and Fate were considered to be his first gods. Why exactly Poros is not clear, because it is difficult to explain the formation of all things from it. It is true that Alkman seems to separate these personified gods and God as the absolute creator. Poros and Fate arose from something, and this something turns out to be the disordered and unprocessed matter of all things (cf. the philosopher Anaximander’s apeiron), which has the properties of copper. The gods arise out of this matter because before there arises “someone who masters” all things, a demiurge named Thetis. This creator creates the gods of the lower order. From Poros arose a god named Tecmor (and they are used synonymously in the beginning-end pair of opposites). Perhaps these two deities were also used as synonyms of the Sun and the Moon. But then according to Alcman, they were preceded by the god of darkness. We know nothing more, but it is enough to see at least ideas about matter, form and demiurge even before Thales of Miletus has appeared on light.

One particular trait of Alkman’s is noteworthy — he boasts that he can eat anything, especially “thesame as the people”; he is not ashamed of it. Interestingly, he generally emphasizes eating, drinking, and, most of all, girls and love pleasures; so it is not surprising that much space in Alcman’s poems is taken up by the god Eros. But, together with what has been said before, all this seems rather strange for a poet of Sparta. Alkman’s poetry seems to preach democratic ideals. And the weirdness doesn’t end there. Alkman is credited with a very lively and modern in its spirit and style epigram about Castor and Polydeucus. Despite the fact that these are Spartan heroes, and that he himself is a Spartan poet, Alcman seems proud to be a non-Greek tiller of the soil, and emphasizes his urban and metropolitan origins in one of the poems where he recalls Sardis as his home.

Alcman resurrects the subjects of the “hedonistic” singers of the past, and again he has glimpses of the shortness of life, the omnipotence of fate (ananke), and even passages a little strange for a Greek man, along the lines of “if only a woman were to become me!”. We even find in him the lines: “experience is the foundation of knowledge”; though, of course, here he means mere worldly experience (and we shall see a similar quotation in the maxims of Pherekides). In Alcmanus we shall also find motives of pacifism (“The iron sword is not above the beautiful playing of the kyphar”). All this modern criticism is accustomed to see as a generation of the later Hellenistic epoch. The more interesting, and even more significant in such a context, these old lyricists and sages look to us.

How such conventionally progressive motifs are combined with a pro-Spartan direction, which is a striking exception to many dozens of other cases, is a question that has yet to be resolved.

Like Alcmanus, we can also find motifs of pacifism in Stesichorus of Sicily (630-556). Although he himself was not averse to writing about heroic wars, especially from the Homeric myths, in his conservative and military pathos he sometimes reaches very stoic maxims, such as “it is useless and not at all necessary to weep for those who have died”. And let it not go beyond the old morality of the ancestors, or poetry of Tirtheus, and quite logical for a patriarchal and paramilitary worldview, and let the Stoicism itself does not claim to a high degree of intellectuality. But, nevertheless, if Stoicism is a philosophy (and it is), then finding analogies in the past can be a useful thing, especially if in the future we find Stoic references to the same Stesichorus.

So, the Byzantine collection “Suda” attributes to Stesichorus 26 books (more than all other Greek lyricists combined), in which the main place was occupied by lyrical and epic poems (in content adjacent to the epic of Homer and the Cyclics; in them Stesichorus gives the processing of old stories in new forms and new interpretation). To the Trojan cycle of Stesichorus belong: “Helen,” ‘The Destruction of Ilion,’ ‘Returns,’ and ”Oresteia.” To the Theban cycle include “Eryphila” (named after the wife of a member of Seven’s campaign against Thebes), and “Europaea”. Of other epic poems are known “Hunters of the Boar” (about the hunt for the Calydonian boar), “Geryoneida” (about the campaign of Heracles to the far west, whence he led away Geryone’s herds of bulls), “Scylla” (about Scylla, which Heracles killed on his return from Geryon), ‘Kerber’ (about Heracles’ feat with Kerber), ‘Cycnus’ (about Heracles’ duel with the son of Ares, Cycnus, who was turned into a swan).

When processing the plots found in Homer’s poems, Stesichorus sometimes gives them new versions, borrowing material partly from living folk legends, partly from lost literary texts. Thus, the myth of Orestes is developed by Stesichorus differently from the version presented in the Odyssey: in Homer’s Orestes, having killed his mother, only fulfills the duty of revenge, while in Stesichorus’s he is tormented by the torments of conscience as a mother-killer. He also has a version of the myth that Helen was carried by the gods to Egypt during the siege of Troy. Both of these versions, as well as a large degree of emotionality of poetry — formed the basis of the tragedies of Euripides. Also the love motif in Stesichorus is quite strong; suffice it to say, it is from him that the first pastoral idylls are derived.

The poetry of Stesichorus was highly valued in antiquity. Thus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus reports that Stesichorus surpassed Pindar and Simonides in the significance of his plots, and in other respects combined the merits of both. And such a tragedian as Aeschylus — created his “Oresteia” under the influence of “Oresteia” Stesichorus. It was even claimed that “the soul of Homer lives in Stesichorus”. And the famous late-antique literary critic Pseudo-Longin called Stesichorus “the most Homeric” of poets, and Quintilian said that Stesichorus “raised on his lyre the weight of epic verse,” and added that “if Stesichorus under the excess of talent did not overstep the measure, he could be considered a worthy rival of Homer”. But in all these characteristics he adheres rather to the “Cyclics,” and looks like the last representative of them, though in manner of performance it is still a new lyric.

Alcaeus and Sappho — a Romance in verse.

The two central figures of lyric poetry of the pre-philosophical period are undoubtedly Alcaeus and Sappho. They lived in the same place, belonged to the same conventional political grouping and were direct contemporaries, with only a slight difference in age, and I will start, however, with the better known Sappho (c. 630 — 570 BC). She differs sharply from all her predecessors and contemporaries, and even later on few people managed to reach her level of lyricism. Against the background of other poets of her time, she stands out strongly with her more practiced style; better conveys passions and emotions, more and deeper reveals the very feeling of love. She also begins to have near-philosophical maxims reminiscent of the famous “sages”:

«Wealth alone is a bad companion without virtue around. If they are together, there is no greater bliss.»

“I love luxury; splendor, beauty, like the shining of the sun, charm me…”.

Unlike most poets (who were men) Sappho writes about “typical femininity” and the experiences of a girl, so, for example, she is angry that a good guy fell for a “hillbilly” who does not even “know how to wear dresses”. There are also “philosophical” musings; apparently about what kind of guys one might like more:

«Who is beautiful — he alone pleases our sight,

Whoever is good — he himself will seem beautiful”.

Sappho’s lyrics are based on traditional folkloric elements; they are dominated by motifs of love and separation, set against the backdrop of bright and joyful nature, babbling brooks, smoking incense in the sacred grove of the goddess. All her poems are imbued with kindness, they concern weddings, dances and other easy joys. Traditional forms of cult folklore are filled with personal experiences in Sappho, the main merit of her poems is considered intense passion, naked feeling, expressed with extreme simplicity and brightness. Love in the perception of Sappho — a terrible elemental force, «sweet and bitter monster, from which there is no defense. Sappho seeks to convey her understanding through a synthesis of inner sensation and concrete sensory perception (fire under the skin, ringing in the ears, etc.).

One of her poems reveals the essence of the provinciality of the Greeks, their sense of their periphery, their secondary status after the Ancient East, which Herodotus would later reveal perfectly. Thus, Sappho praises the very Lydian Sardes (which played a great role for Alkman), where one of her friends went to live. Her father Scamandronimus was a “new” aristocrat; being a member of a noble family, he did not farm the land, but rather was a merchant. In the middle of the 7th century BC, the royal power in Mytilene was abolished and replaced by an oligarchy of the royal Penfelid family. Soon the power of the Penfelids also fell as a result of a conspiracy, and a struggle for supremacy broke out between the leading aristocratic families. In 618 BC the power in the city was seized by a certain Melanchrus, whom the ancient authors call the first tyrant of Mytilene. Soon Melanchrus, through the combined efforts of the poet Alcaeus, his brothers, and the future tyrant of Mytilene Pittacus (by the way, included in the list of “Sages”), was overthrown and killed. The tyrant of Mytilene became their ally Myrsil, whose policy was directed against certain representatives of the old Mytilene nobility, and many aristocrats (including the families of Sappho and Alcaeus), were forced to flee the city somewhere between 604 and 594 BC. Until the death of Myrsil — Sappho was in exile and lived in Syracuse (between 594 and 579 BC), after which she was able to return to her homeland. According to legend, it was at this time that Alcaeus became infatuated with her.

Alcaeus himself (c. 625-560), a poet who was a contemporary and compatriot of Sappho and the tyrant Pittacus, was also born in Mytilene. When the royal power in Mytilene fell and the first “tyrant” of the city, Melanchrus, came to power, Alcaeus himself was about 7-13 years old, Sappho was about five years older than him. Soon after these events Alcaeus, just coming of age, entered military service; and at this time there was a war against Athens, in which Mytilene was defeated.

In the battle Pittacus, a comrade of Alcaeus, distinguished himself greatly, and in a key battle of the war Alcaeus himself escaped by throwing down his shield (if this verse is not a mere imitation of Archilochus’ verses). And when, after the participation of Alcaeus and Pittacus in the coup, a certain Myrsilus became the new tyrant of Mytilene, the position of Pittacus himself (a former ally of Alcaeus and one of the “seven sages”) changed after a while; he sided with the new tyrant and was his co-emperor for some time. When this happened, Alcaeus immediately attacked Pittacus in his poems, which in a poet may be considered the most offensive. The reply was not long in coming, and was not at all poetic, so Alcaeus had to flee from the city. He (like Sappho) was in exile at least until the death of Myrsilus (between 594 and 579 BC).

Alcaeus also has a place for Homeric myths and divine power, but this is no comparison with Stesichorus. And what distinguishes Alcaeus from his contemporaries is that he is openly opposed to the tyranny of Pittacus (which is anti-aristocratic in character), and is concretely political in his poetry.

“Our fate is in the balance: everything will be overturned upside down if he, the madman, takes power in the city…”.

or

«The predator seeks to reign,

«He wants to reign, he wants to rule,

«He’ll turn everything upside down

«the scales are tilted. What are we sleeping?»

He also composed hymns, one of which, “To Apollo,” is dedicated to the patron god of aristocrats. Though, to be fair, in the lines about drinking, he doesn’t mind “swearing an oath to Dionysus” either. When his conspiracy against Pittacus failed and he was banished, he began a streak of “whining”.

Most of the poems of his so-called “Stasiotica” (rebellious songs) should be attributed to this period of exile, in particular the most famous ode-allegory about the “ship-state” and the no less famous “ode of arms”. While in exile, the aristocrats did not forget their intention to restore the old order in Mytilene and continued to intrigue against the city government. Finally, the party of the aristocrats gained such strength that the threat of their return to Lesbos in the form of a military invasion became real. Mytilene succumbed to fear; in 589 the city elected an esimnet, who became Pittacus; he was given a term of office of 10 years, was to strengthen the city and lead the democrats in a likely conflict with the aristocrats, whose leader was Alcaeus. About 585 B.C. (when Thales predicted the famous eclipse) Alcaeus, who had become the head of his party and was supported by the gold of the Lydians — returned to the island, but was again defeated in new clashes. Pittacus did not punish his old comrade and released Alcaeus (noting, in the words of Heraclitus, that “it is better to forgive than to avenge”), and he passed from the historical stage, living out his life in silence, according to legend, going to Egypt.

In most of his poems Alcaeus merges with the spirit of Alcman, and in some places even more radically in favor of amusement and revelry. In him one can find a strange panchline about the romance of sea travel, and an ironic attack against those who fear the sea (incidentally, Pittacus disliked the sea). And what is most interesting, this ideological defender of aristocratic valor, not only glorifies wine, but also describes in verse how he fled in battle and lost his armor and shield. What could be more shameful for an aristocratic supporter? And is his temporary victory with the help of a bribe from the Lydian king a worthy thing to mention in several different verses? Along with this, another point is interesting; it turns out that Alcaeus’ brother served in the army of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, which Alcaeus mentions in one of the verses; an aristocrat, serving as a mercenary!

Another thing is also striking, referring to the legendary king of Sparta (by the way Alcaeus also paid tribute to Castor and Polydevk), we again get an unexpected outcome for the image of Sparta’s admirers:

Thus said Aristodamus

The sensible word in Sparta:

«In wealth is the whole man;

He who is good but miserable is nothing”.

True, despite the atypical for Sparta denial of asceticism, the motive of this saying is rather that wealth is a sign of aristocratism, and this is quite consonant with the pro-Spartan support of the “high-born”. As for the famous affair between Alcaeus and Sappho, there is little or no information about it, and his own poems are absolutely nothing, and say only that he is very embarrassed in front of her and that he is an embarrassed “hick”. So later on Sappho responds to his poems quite appropriately:

«Be thy purpose beautiful and high,

Be not shameful what thou wilt say, —

Ashamed, thou wouldst not lower thine eyes,

Thou wouldst say what thou wilt

The beginning of an open ideological conflict

In the 580s and beyond, the poet of greatest interest to us is a younger contemporary of Epimenides and Mimnermus; Thales and Sappho — the aristocratic poet Theognides of Megara, exiled from his hometown by the radical democratic “revolution”. Among the instructions of Theognides there is, along with the traditional aphorisms about piety, reverence for parents, etc., a large number of poems on topical political themes; they represent one of the most striking examples of the aristocrat’s hatred of democracy. It is a compound of all that is most conservative of the poetry of Tirtheus, Callinus, and Alcaeus.

For Theognides, slavery exists by nature; men are divided from birth into the “good,” i.e., aristocrats, and the “mean.” “Good” are automatically inherent in all possible virtues: they are brave, straightforward, noble; ‘mean’ are inherent in all vices: baseness, rudeness, ingratitude. However, the “mean” get rich and become in power, while the “good” are ruined and therefore the “noble” gradually turns into a “low”. In relation to the “mean” for the “good” all means are allowed. Theognides is a preacher of violence and cruelty, even outright hatred of all these “freighters” and “ship’s blacks”. He wants “a strong heel tocrush the unreasonable nobility, bend it under the yoke”. But he treats the “noble” no better, because the “noble” themselves are mired in greed and money fetishism. Theognides sharply condemns the marriages of aristocrats to “inferior” people for the sake of their money. He also wholeheartedly condemned the conflicts of the various clans of the aristocracy among themselves, seeing in this the weakening of their conventional “party”.

Theognides, with his belief in the innate moral qualities of the “good” man, expectedly became one of the favorite singers of the Greek aristocracy; it preserved his poems, supplementing the collection with thematic poems by unknown authors. Theognides fit perfectly into the context of the paramilitary lyrics of Tirtheus and Callinus, which were to dominate the other authors of this new collection.

A notable contemporary of Theognides was the satirical poet Hipponactus of Ephesus (ca. 580-520). Taken together, they seem to complete the early poetic history of antiquity and echo the new, philosophical generation. By the time of Hipponactus’ death, for example, Heraclitus, though only a 20-year-old youth, was already living.

Hipponactus came from an aristocratic family; but he was banished from the city for attacking the local rulers; so he moved to Clazomenes (a town nearby, where the philosopher Anaxagoras would later be born), where he led the miserable life of a “jester and joker.” The dates of his life suggest that Hipponactus caught the capture of Clazomenes by King Croesus, as well as the fall of Croesus himself and the advent of the Persian monarchy. From the work of Hipponactus about 170 passages have survived, in which he depicts the life and life of the urban lower classes, without stopping and before frank naturalism. Other passages depict small artisans and representatives of the social bottom, spending time in the city nooks, suspicious pubs, hapless peasant or cunning artist, belonging to the same layer of “the dregs of urban society”, all of them engaged in dark deeds, often resolving disputes with the help of scolding and beatings. Hipponactus portrays himself as a half-starved ragamuffin, expressing his hostility to the aristocratic worldview. In this respect, he already reminds us of the outlines of the Cynic worldview.

Several of his poems parodying Homer and the Homeric epic are consistent with this social position. A special place is occupied here by one hexametric fragment in 4 verses, probably from a heroic-comic poem, praising in Homeric epithets the monstrous appetite of a certain Eurymedontiad. These two passages prove that Hipponactus was not alien to the literary tradition (in addition to the fact that the extant fragments of poems themselves testify to the high level of his poetic training). The image he created of a beggar-beggar is most likely a mask designed to “epathetize” his listeners.

In connection with Hipponactus (perhaps someone from his direction, but a little later) there arises a parody of a heroic epic called “The War of Mice and Frogs” (“Batrachomyomachia”), which we recommend to read in full. The subject of this parody is both the aristocratic heroics of the epic, its Olympian gods, and the traditional devices of epic style, beginning with the obligatory invocation of the Muses in the introduction. The frog king Vzdulomorda, carrying the mouse Krohobor on his back across the swamp, was frightened by a water snake, dived to the bottom and sank the mouse. Krohobor belongs to a distinguished family, has a whole pedigree. A war therefore breaks out between the mice and the frogs. Both militias are armed according to the epic pattern; namely, we are shown the gradual appearance on the stage of the armament of both sides in all sorts of detail (naturally of the “helmet — walnut shell” level). The Olympian plan, i.e. the council of the gods, is also introduced. The parody of the gods is extremely sharp and probably already ideologically connected with the philosophical criticism of mythology. Athena refuses to help the mice for reasons of extremely insignificant offense:

The peplos were chewed then, which I worked on for a long time,

Soft fabric I wove on a thin base.

They turned it into a sieve! And the mender, for the sin of it, has come,

He’s asking for interest, which is always depressing to immortals.

And in general, the gods better not interfere:

Gods! Let’s not interfere in their fights! Let them fight themselves,

Let none of us be wounded by their arrows.

Their power is daring, even with immortals.

If the author is not Hipponactus himself, he is certainly one of the main inspirations for this magnificent poem.

Thus Hipponactus forms together with Theognides a kind of contrast of opposite extremes. Of course, even before the aristocrats had their ideological poetry, and a vivid expression of this political conflict was the struggle between Alcaeus and Pittacus, but until now the anti-aristocratic (i.e. in essence already democratic) side did not have consistent supporters, and the opposition had only an accidental character connected with the personality of a particular poet.

Hipponactus is a conscious opponent of aristocracy.

In the images of Theognides and Hipponactus, the conflict between the aristocracy and the people finds its extreme expression, but still in its simplest form. The “philosophical turn” that would give this conflict more gravity was just beginning to emerge. The Greeks themselves considered the beginning of this turn to be the sayings of the Seven Wise Men, among whom was the famous Thales of Miletus.