Pre-Philosophy Cycle:

- The beginnings of philosophy in India and China.

- Eastern influence (Phoenician, Egyptian and Babylonian philosophy).

- Mythological stage (compressed mythology).

- Heroic stage (compressed stories about heroes).

- Homeric period, Cyclic poets and Orphism.

- Context, role of tyrants and kings.

- Nine Lyrics.

- Seven Sages.

- Formation of classical theology — you are here.

- Pre-philosophy (final paper).

- The Conflict of Pindar and Simonides (taken out of the series, will post elsewhere).

As we have seen, the author of the “Telegonia”, Eugammon of Cyrene, was a contemporary of Thales, and thus a contemporary of a full-fledged philosophy, the so-called “Canon”. Some of the Cyclic poets developed at the same time as the early “Nine Lyricists” or “Seven Sages.” All of them, from Homer to Eugammon, systematized Greek mythology and religion. However, their works were disparate; they were written by different people and at different times. Moreover, if we accept that Homer did not exist as a real person, then the work of many wandering poets had to be collected, recorded and systematized into a unified whole by someone. The ancient Greeks even gave the names of these systematizers. We call the result of their work “classical theology.” In the following sections we will deal mainly with metaphysical, i.e., philosophical theology, but “classical” will always be implied somewhere in the background as the most traditional form of worldview in Greece.

The Theology of Wonderworkers

Philosophy in Crete, where all Greek civilization actually began, was represented by Epimenides (ca. 640-570), who is also sometimes listed as one of the “Seven Wise Men”. He was born in Festus, and later lived in Knossos; ancient tales portray him as a favorite of the gods and a successful soothsayer. According to Aristotle’s already rationalized interpretation, it is believed that Epimenides did not predict the future, but only clarified the dark past (i.e., he was a historian). He was considered the author of the books “Genealogy of the Curetes and Corybantes”, a large book “Theogony” (5 thousand verses), “The Construction of the Argo” and “Jason’s Voyage to Colchis (6.5 thousand verses together). In addition, he wrote a prose book “On Sacrifices”, historical and political work “On the Cretan polity” and “On Minos and Radamantes”. When the Athenians after the rebellion of Kylon wanted to cleanse themselves from “Kylon’s curse”, they invited Epimenides to offer purification sacrifices (596 BC); and then Epimenides performed the sacrifices, and as a reward took only a branch from the olive tree dedicated to Athena, after which he concluded a treaty of friendship between the Knossians and the Athenians. That is, he acted as a Cretan diplomat and politician. It is believed that he became friends with the sage Solon and influenced the reforms of the Athenian state system, and taught the citizens of Athens to be more pious and moderate in their lives, for which he was highly respected by ordinary Athenians.

In short, Empimenides fits perfectly into the context of the work of the Cyclic poets and Orphic theology. Stories of miracles are also associated with him. According to legend, Epimenides fell asleep as a young man in the enchanted cave of Zeus on Mount Ida and awoke only after 57 years (and somewhere around this time he was visited in the cave by the philosopher Pythagoras, in the process of his move to Italy). This myth formed the basis of Goethe’s “The Awakening of Epimenides”. According to another version, while in the cave, he fasted and stayed in prolonged ecstatic states, being on a special diet, which was so simple that from such food he did not even have excrement. Epimenides was therefore often cited as an exemplary ascetic. In any case, he left the cave in possession of “great wisdoms.” Among such wisdoms, Epimenides is credited with a verse on the deceitfulness of the Cretans (quoted in the New Testament from the Apostle Paul in Titus 1:12), cited long ago in logicians as an example of a vicious circle; it reads “All Cretans are liars.” Since Epimenides was himself a native of Crete, this statement becomes problematic. If we assume that the statement is true, then it follows that Epimenides, a Cretan, being a liar, told the truth, which is a contradiction. Thus we can see the rudiments of dialectic and sophistry as early as in “pre-Phalesian” literature.

It is also reported about a special cosmogonic doctrine, which terminologically and in its meaning adjoins the cosmogony of the Phoenicians; for example, according to Epimenides, the world had two beginnings — Aer and Night (which, if we believe the extant evidence, were considered important beginnings by such Phoenicians as Sanhunyaton and Mochus). And according to one version, Epimenides is also credited with the words quoted by the Apostle Paul in his speech in Athens (according to other versions, Paul quotes the philosopher Cleanthes, or the poet Pindar): “for by him we live and move and exist, just as some of your poets said, ‘we are his and his kind’.” In principle, the ideas about “air” and “night” converge perfectly with Orphic theology, represented also by Pherekides, whom we will consider a little below.

Besides Epimenides, another poet who was a little more than a generation older than him came from Crete, Phaletes of Gortyna (ca. 700-640), a contemporary of such lyricists as Tirtheus, Semonides, and Callinus. He was invited to Sparta as the founder (or reformer?) of the Hymnopedia festival, and as a teacher who prepared Spartan choirs to perform at this most important festival for the Spartans (traditional dating: 665 BC). Already at the end of antiquity, Boethius in his work “Fundamentals of Music” reports that the Spartans preserved beautiful music for a long time thanks to the activity of Phaletes, who taught their children the art of music, having been invited from Crete for a great reward. In other words, Phaletes laid the foundations of Spartan musical education, the very existence of which explains the long and stable Spartan superiority in the musical sphere throughout the Greek world. Some ancient testimonies have been preserved that Phaletes, using music, pacified the internal turmoil in Lacedaemon. These are, first of all, Fr. 85 of the Stoic Diogenes of Babylon and the Herculaneum papyrus with the text of the treatise “On Music” by the Epicurean Philodemus of Gadara; it is also mentioned in Plutarch’s “Moralia”. All this is very similar to the activities of Epimenides, which he allegedly conducted half a century later, so perhaps the myths about them simply intermingled. By the way, the already mentioned conservative poet Tirtheus lived in the same Sparta at the same time as him, which brings these early poets very close together.

Similar to Epimenides and Phaletes is also Aristeas of Prokonnese (c. 7th century BC), a traveler and “miracle worker” about whom Herodotus tells. He wrote the «Arismapic Poems”, an account of the Hyperboreans and Arimaspes in 3 books (and thus was a historian and geographer). He also rewrote Hesiod’s Theogony, in prose form. This moment is not unimportant, because it shows the freedom in dealing with the “great” authors, having almost religious significance for the ancient Greeks. In addition, prose translations always hint at the fact that the text has a wide mass reader; as we know, the aristocracy is quite comfortable with reading the verse form. The primitiveness of the Orphic and Pythagorean worldview is symbolized in some way by their belief in the existence of Abaris , another diviner and priest of Apollo. Abaris is thought to have come from Scythia, or directly from the land of the Hyperboreans. According to legend, he did without food, and flew on a magic arrow given to him by Apollo himself, which is why the Pythagoreans called Abaris “Air-breathing”. He allegedly traveled all over Greece, where he healed diseases with a word alone. He also built the temple of Kora the Savior (Persephone) and composed all kinds of sanctifying and purifying incantations, so that once stopped the plague raging in Sparta (this again coincides with the same stories of “purification” associated with Epimenides and Phaletes). Such an early belief in itinerant hermit miracle-workers, against the background of the primitive folk theology of the Orphics and Dionysians, makes the appearance of Jesus seven hundred years later not so surprising.

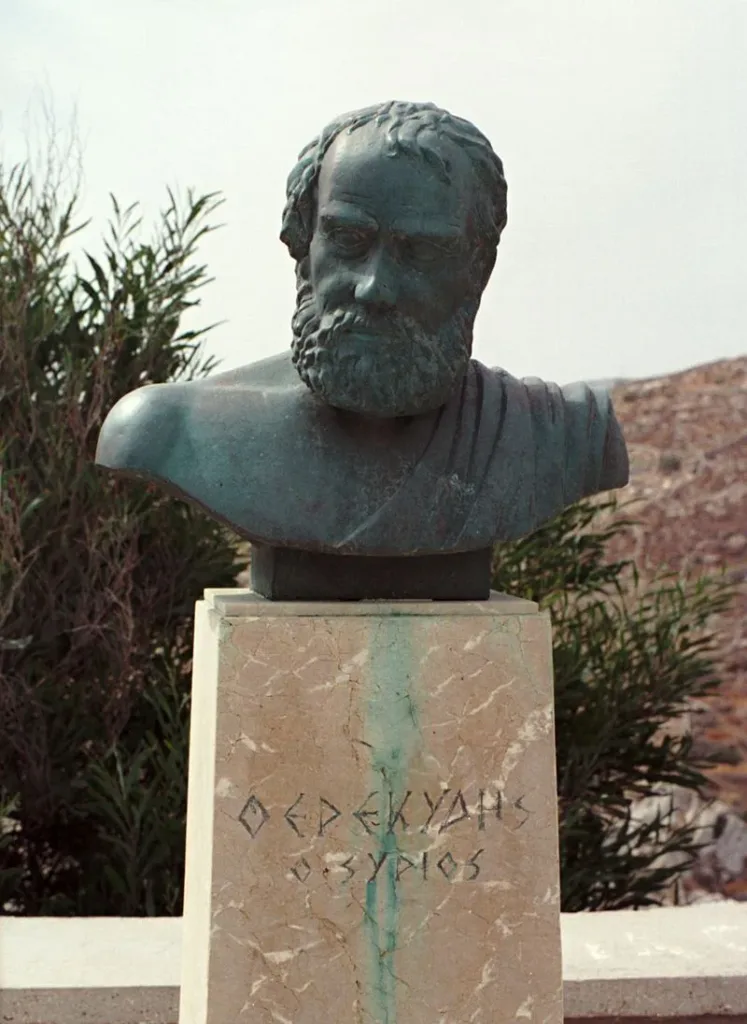

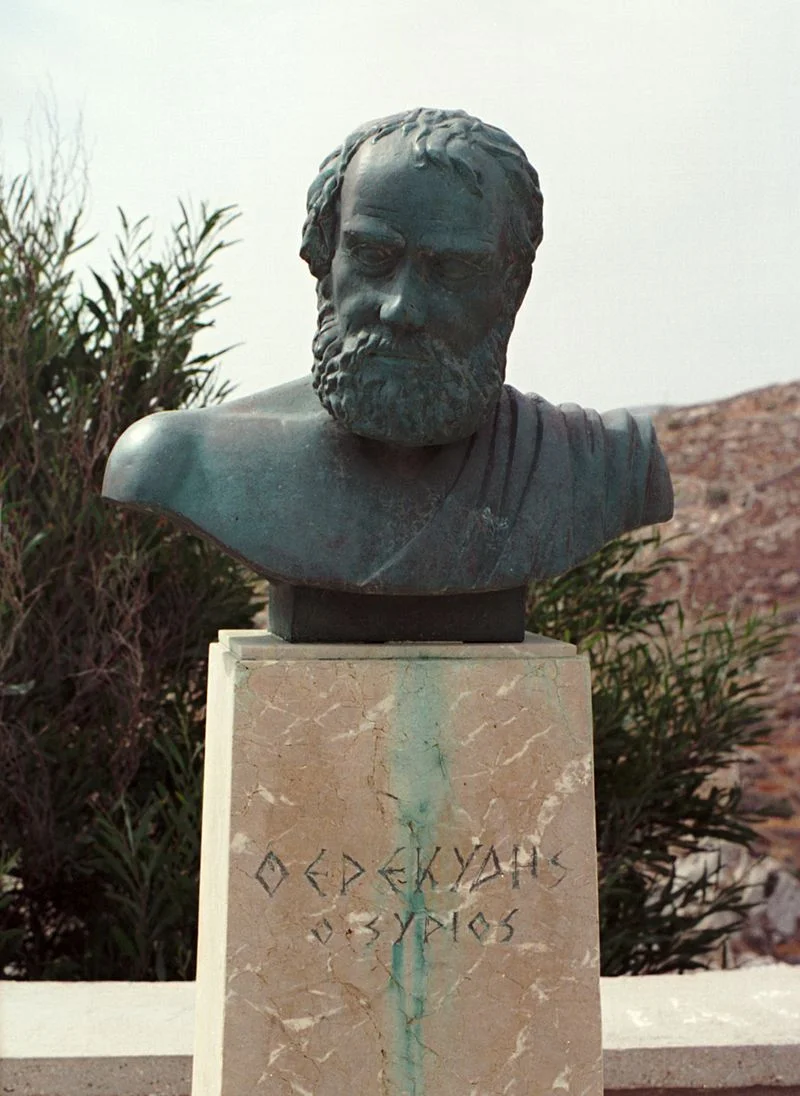

Theology in the poems of Pherekidus

Adjoining the Orphic cosmo-theogony is the worldview of Pherekides of Syros (c. 580-499). This contemporary of the philosopher Anaximander was the author of a book called Cosmogony. His home island of Syros, near Delos (the center of the Greek cult of Apollo), was in relative proximity to Athens, and judging from his years of life he may well have been personally acquainted with many of the region’s figures, such as Simonides. Authors such as Clement of Alexandria and Philo of Byblos state that “Pherekides received no instruction in philosophy from any teacher, but acquired his knowledge from the secret books of the Phoenicians.” It is stated that he then became a disciple of Pittacus and lived on Lesbos. It is also mentioned that he traveled in Hellas and Egypt. This makes him yet another Greek who was simply transferring knowledge from the East to Greek soil.

Pherekides is considered one of the first Greek prose writers (Aristeas, Epimenides and Anaximander could argue with this). Pherekides’ largest book, entitled Cosmogony, adjoins Orphism in its content and resembles the work of Epimenides. In his Cosmogony, Pherekides recognized the eternity of the initial trinity of gods: Zas (a variation of Zeus, the etheric heights of the sky), Chthonia (the maiden name of Gaea, the subterranean depths), and Chronos (time). Zas becomes Zeus as the bridegroom of Chthonia, who as Zeus’ bride takes the name of Gaea (hence another title of his work, The Confusion of the Gods). And in other words we can say that under the action of time in the marriage of earth and sky all our visible world came into being. Pherekid proclaimed the eternity of the originals of the universe. It is known that Pherekid’s work began with the words “Zas and Chronos were always, and with them Chthonia”. Therefore, in his “Metaphysics” Aristotle not in vain calls Pherekidus among those ancient poets-theologians, “whose presentation is of a mixed character, since they do not speak of everything in the form of myth.” Pherekid also distinguished between three basic elements: fire, air, water — which Chronos created from his seed, and which further break down into five parts (according to Gompertz: the spaces of stars, sun, moon, air and sea), from which supernatural beings, a new generation of gods, arise. These are the Okeanides, Ophionides, Cronides, demigod-heroes and demon-spirits. Ophionides personified the dark chthonic forces. They are led by the serpent Ophion. They oppose Zeus, who after a brutal cosmic war overthrows them into Tartarus. In this struggle Zeus was supported by the Kronids, i.e. the Titans led by Kron. Obviously, Pherekid’s conception is more reminiscent of Orpheus’ work than Hesiod’s Theogony. The Theogony of Pherekidus also shows similarities with Orphic theogonies, such as the Orphic Hymns (created parallel to the Homeric Hymns, with the same purpose and similar content, but in a particular, “Orphic” style of telling the story of the gods). Both the Pherekid and Orphic hymns depicted primordial serpents and eternal Time as a god who creates from his own seed through masturbation. Such Orphic aspects also appear in Epimenides’ Theogony. Pherekid probably influenced the early Orphicists, or perhaps he was influenced by an earlier sect of Orphic practitioners; more likely Pherekid acted as one of the first systematizers of Orphism and the classical Olympian religion into a unified whole.

Like many other of the poets and “sages” of the early period, Pherekidus is considered to be the author of “gnomes,” i.e., short sayings of wisdom, which in fact turn out to be rural sayings, and are most likely attributed to all these authors much later. Several of the most interesting ones can be distinguished from those of Pherekid:

- Whoever wants to be virtuous is partly already virtuous.

- Stupidity, laziness and vanity forever go hand in hand.

- The best is the enemy of the good.

- If poverty is the mother of crime, laziness is its grandmother.

- Idleness is the mother of all vices and diseases.

- Patience and labor give more than power and money.

- Trusting your intuition is the first condition for great endeavors.

- Instinct and reason tear the soul in different directions.

- Knowledge not born of previous experience leads to mistakes and unnecessary suffering.

- The diamond is polished by the diamond, and the mind is polished by the mind.

- Geniuses stand on the shoulders of titans.

- He who does not appreciate eternal life does not deserve it.

Pherekides was famous for predicting the fall of the city of Messenia in the war with Sparta, shipwrecks, and especially earthquakes. Allegedly, he could predict an earthquake three days before it started, by the taste of water from a deep well (it was recently discovered that before the earthquake in the underground water really changes the concentration of gases and isotopic composition of chemical elements). Interestingly, earthquakes could also predict Anaximander of Miletus, and the structure of his cosmogony, according to Damascus, reveals similarities with the cosmogony of Anaximander. Indeed, in both of them the firmament breaks up into a number of autonomous spheres. The sundial (heliotropion) supposedly made by Pherekidus, according to Diogenes of Laertes, “survived on the island of Syros” even in his time. Finally, Heracles is said to have visited him in a dream and told him to tell the Spartans not to value silver and gold, and on the same night Heracles is said to have told the king of Sparta to listen to Pherekides in a dream. However, many of these miracles were also attributed to other legendary philosophers, such as Pythagoras or Epimenides.

Pherekides was highly honored by his contemporaries (especially the Spartans) for his purity of life; and a “ήρωον” (“heroic” shrine) was erected near Magnesia in his honor. He is also known for having advanced the doctrine of metempsychos (transformations of souls). According to Cicero: «As far as is known from written tradition, Pherekides of Syros first said that the souls of men are eternal.” In connection with this teaching, he abstained from meat food, which also brings him closer to the Orphic tradition. This is why he was considered the teacher of Pythagoras, as noted by Diogenes of Laertes. It is claimed that after the death of Pittacus, Pythagoras’ uncle invited Pherekides to move to Samos and become the young man’s teacher.

There are many conflicting legends that supposedly tell of the death of Pherekides. According to one story, the Spartans killed Pherekides and skinned him as a sacrifice, and their king kept the skin out of respect for Pherekides’ wisdom. However, the same story was told about Epimenides. Claudius Elianus in his “motley tales” wrote the following about the demise of Pherekidus:

“Pherekides of Syros ended his days in terrible agony: he was infested with lice. Since it was terrible to look at him, Pherekid had to refuse to socialize with his friends; if anyone came to his house and asked how he was doing, Pherekid would stick his lice-ridden finger through the door slit and say that his whole body was like that. The Delosians say that their god, in anger at Pherekid, inflicted this affliction on him. After all, living with his disciples on Delos, he boasted of his wisdom, and especially of the fact that, never having made sacrifices, he nevertheless lived happily and carefree, no worse than people who sacrifice whole hecatombs. For these impudent speeches God punished him severely.

Acusilaus and Theagenes

One of the earliest systematizers of Hesiod’s theology was the historian and compiler of speeches, Acusilaus of Argos (c. 590-525). Although he was of Dorian origin, he wrote in the Ionian dialect. He was sometimes counted among the list of the “seven sages.” He wrote the book Genealogies, a prose historical work, which, however, already in antiquity was considered by many to be not authentic; it has not survived to this day. As the author of genealogies, Acusilaus is mentioned in the Byzantine dictionary “Suda”. The source of his genealogies was, according to the “Suda”, some bronze tables, which his father found in the ground. According to Clement of Alexandria, the historical work of Acusilaus was a prose transposition of Hesiod’s verses (cf. the miracle-worker Aristeas of Prokonnesos), but Josephus Flavius notes that Acusilaus made numerous corrections to Hesiod’s genealogies. Pseudo-Apollodorus refers 9 times to the versions of Acusilaus, noting both similarities with Hesiod and divergences with him. From the theogony of Akusilai, according to Dils-Krantz, only 5 testimonies and three fragments have been preserved, which in addition contain contradictions. Thus, very little is known about the teachings of the sage. According to Eudemus of Rhodes in the transmission of Damascus, Acusilaus believed the original to be the unrecognizable Chaos, from which Ereb (male) and Night (female) emerged. From the union of Erebus and Night were born Aether, Eros and Metis, and from them — many other gods. According to Plato, Acusilaus followed Hesiod in saying that Gaia and Eros were born after Chaos. Another source states that Aksusilai called Eros the son of Night and Aether. Be that as it may, it is obvious that Acusilaus was another systematizer of Hesiod’s and Orphic theology.

Much later lived another writer and philosopher, Theagenes of Rhegium (c. 550-490), known as the first explorer and interpreter of Homer’s poetry, and the first to engage with Hellenic diction. Theagenes employed an allegorical method in explaining Homer’s poems and myths, defending his mythology against more rationalist attacks, perhaps in response to criticisms of early Greek philosophers such as Xenophanes. It has also sometimes been claimed that Pherekides of Syros anticipated Theagenes. And here is what the late antique Neopythagorean Porphyry says about it:

The account of the gods is utterly embarrassing and unseemly: the myths which he [Homer] tells of the gods are obscene. Some find justification against this charge in the manner of expression, believing that it is all told allegorically about the nature of the elements. For example, by the antitheses of the gods [the antitheses of the elements are allegorically expressed]. Thus, dry, according to them, fights with wet, hot — with cold, light — with heavy. In addition, water quenches fire, and fire dries up water. Similarly, there is an opposition [~ hostility] between all the elements of which the universe is composed, and they are partly subject to annihilation at some point, while the whole endures eternally. Their [the elements’] “battles” he [Homer] and sets forth, calling fire Apollo, Helios and Hephaestus, water Poseidon and Scamander, the moon Artemis, the air Hera, etc. In a similar way he sometimes gives names to the gods and to the states [of mind]: reason (φρόνησις) is named Athena, folly Ares, lust Aphrodite, speech Hermes, and assigns them to them. Such is this way of justifying [Homer] on the part of style; it is very ancient and originates with Theagenes of Rhegium, who was the first to write about Homer.

If indeed Theagenes reasoned about Homer in this way, then this allegorism is already entirely philosophical in character. And when Pherecydes is compared to him, this is what is meant, that even in Pherecydes simple philosophical elements and forces were hidden behind the images of the gods. And here it is really difficult to say whether Theagenes was systematizing Homer’s theology, or was turning Homer’s poetry into pure philosophy of nature. But we can clearly see that taking a step from Homer to philosophy was not at all difficult even for the ancient Greeks of the archaic epoch.

Systematizing the theology of Onomacritus

Probably shortly before the death of Theocritus, a compiler of oracle predictions named Onomacritus (c. 530-480), who lived at the court of the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus, prepared an edition of Homer’s poems, where they were first systematized and divided into “books” on the principle we still use today (so Theagenes of Rhegium probably did his research afterwards). The historian Herodotus tells us that Onomacritus was hired by Pisistratus to put together the prophecies of Museus, but Onomacritus allegedly inserted false predictions of his own composition into the text. This forgery was exposed by Las Hermiones (teacher of Pindar and opponent of Simonides), after which Onomacritus was banished from Athens by Pisistratus’ son, the tyrant Hipparchus, but he later reconciled with Pisistratus. According to the report of Pausanias Onomacritus was the first Orphic theologian and poet. His predecessors may be considered Epimenides, Abaris, and other mystics, as well as the work of Pherekides. Next to Onomacritus, Zopyrus of Heraclea, Nikias of Eleia, and the Pythagoreans Brontinus and Kerkops are mentioned in a similar role. All of them were considered to be the compilers of such mystical poems.

Onomacritus in the Orphic verses [believed the beginning of all things] to be fire, water, and earth.

It is true that the fact that he was engaged in publishing a corpus of Homer’s works makes him something more than just another systematizer of Orphic theology. He may be considered a systematizer of all Greek theology in general.

In later times of Hellenistic Greece and Rome, the works of Orpheus, Museus and Linus were considered to have been created by the hand of Onomacritus (well and prolific Onomacritus in this case, whose works are searched for by the score of dozens, and the sources show that these three authors also refer to each other, which required an elaborate hoax). Therefore, there is a high probability that Orpheus and Linus are a solid modernization. At least, for the sake of saving the honor of Parmenides, any researcher will defend this point of view to the last, and otherwise most of the major philosophers of pre-Socratics will turn out to be banal relayers of Orphism ideas, and it will devalue the whole “breakthrough” of future philosophers. Yes, of course, the stories about the “seventh day” look too much like Christianity, and all the above about Linus looks like a retelling of Parmenides or Empedocles — and one can decide that the author of the forgery knew Christianity and early Greek philosophy.

So it is officially believed that the “Orpheus” available to us, as well as the familiar to us “Homer” — is a generation of the era of Pisistratus, i.e. contemporaries of Heraclitus and Parmenides. Hence the great number of similarities. There is also an interesting testimony that “Heraclitus and Linus defined the great year as 10,800 years”. It is impossible to prove that Onomacritus, Zopyrus, Heraclitus and Parmenides did not use the same source. Nor is it possible to prove that philosophers copied from court theologians, or vice versa, that court theologians copied from philosophers. Therefore, we assume that a common source from the time of Homer — could well exist. We shall proceed on the presumption of confidence in the sources, and moderately admit the existence of the philosophy of Linus and Orpheus, just as in the case of Mochus of Sidon. As to what this common primary source might have been, we assume it to be the generalized philosophical views of the Phoenicians, Babylonians, and Egyptians.

In any case, Onomacritus’ writings became a boundary, a “slice” in the development of ancient Greek religion. It is quite possible that to this “slice” the philosophical concepts already known at that time were added, strengthening some aspects of the original religion. But it is highly unlikely that literally all archaic sources were written by a single deceiver. Thus, sages named Epimenides, Aristeas, Pherekides, Acusilaus, Theagenes, and Onomacritus (and maybe Zopyrus, Nicius, Brontinus, and Kerkops) became systematizers of the theology of Homer, Hesiod, and the Orphics. It is quite obvious that most of the Nine Lyricists, the Seven Sages, and the philosophers of the Canon— shared their views, though the further we go into the future, the less influence of theology and the more common are secularized views, especially among philosophers.

Добавить комментарий