This article is a kind of bridge between the «Prephilosophy» series (the previous article in the cycle) and the «Formation of the Canon» series (the next article). In a way, it touches on both of them.

Thales, the first empiricist

“To begin philosophy with Thales” has long been a good tradition, and even in antiquity itself it was considered that Thales of Miletus was the first philosopher, and the first to reason about nature. But after excursions in history of the East and the analysis of poetic tradition, we already understand that everything is not so simple, in fact even in antiquity itself which has created habitual to us image of Thales as the first of philosophers, in cohort of philosophers many of his predecessors were included. We ourselves have seen that Thales was in the context of the activities of the “Nine Lyricists” and the “Seven Sages”, who are no longer classified as philosophers. And this ancient idea of Thales as a man equal to the “Seven” was in many respects justified, because from what we know about Thales — his level of thinking barely went beyond the simplest notions, which had already Solon or Pittacus (notions at the level of mother should be respected, honor should be cherished, friends should not be deceived, etc.). In cultural and world outlook Thales is an open conservative. But we have already considered the fables about Thales, and if we speak about him as a philosopher, the only thing in which he really made his mark as a unique personage was the creation of a special philosophical “school”; or rather a chain of succession of thinkers. This group of sages is now called by us after their place of residence: the “Milesian School”, or even more broadly, the “Ionian Philosophy”.

Certainly, all it is so, only if to consider as a fiction existence of school Mochus from Phoenician Sidon (one of applicants for udrevlenie atomistic philosophy). If Mochus existed, then Thales borrowed the concept of the philosophical school from the Phoenicians. As we shall see further, the most part of views of Thales perfectly lays down in a context of occurrence of views of Phoenicians (earlier we have already told that Thales on blood was rather Phoenician, than Greek), and ancient biographers insisted that he has transferred many knowledge from Egypt. The years of Thales’ life are known presumably (c. 630-548 BC). He is about the same age as Sappho, Alcaeus, Mimnermus, Stesichorus, Solon, Pittacus, and many others. At quite a conscious age his life must have been caught even by the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus. Therefore, we should not think that the “Milesian School” opens some fundamentally new era in Greek culture, it arises synchronously with other cultural phenomena. Up to our days almost no authentic passages have survived, where the philosophy of Thales “in the first person”. Literally few passages have survived, as presented below:

“The primary element Thales supposed to be water» (1). “The earth is held on water, like a plank or ship on the sea, surrounded on all sides by the ocean” (2). “Thales hypothesized that the soul is something that moves. Stone has a soul because it ‘moves’ iron” (3). “Thales was the first to proclaim that the nature of the soul is such that it is in perpetual motion or self-movement” (4). “According to Thales, mind is the deity of the universe, everything is animated and full of daemons” (5).

And what is important to note here is that Thales is interested in the problem of motion; and this is a very important problem in the history of philosophy. Now we are not talking about the physics of any particular motion, but about the independent motion of the whole Universe, about motion in the broadest sense, almost about “motion as such”. From this another theme inevitably develops; that since the cause of motion is the soul (it is also the cause of the will of our body, and it is the will that pushes us to motion), then it follows that since the whole universe is in motion, the soul is not only in living beings, but absolutely everywhere. This view would later be called “hylozoism”; although it is obvious that Thales was not its discoverer; it is a pre-philosophical, primitive and ancient view, observed even among Stone Age people or in the Greek Olympic religion. The main feature of Thales in this context is that he calls Mind the world god. We do not know how this relates to the rest of Thales’ ideas, but in the next generations philosophers will deal with this very thing: the harmonization of nature and Mind. The hypothetical fragments of Thales from the collections of statements of the “sages” say more about it, and we will take them into account in the further presentation.

The theme of “water” as a primary element, strange as it may seem, is not so interesting at all, and even trivial. Already if only because the ideas about philosophical elements existed both before Thales and during his life — and these ideas were already then more developed. Thoughts about the “water beginning” simply repeat mythology, both Greek and Eastern, where at the beginning of time there was no land on earth yet, and the whole world was “Chaos”, or more often “Ocean” (the ancient poets themselves, the same Homer, could consider them synonyms). The cosmogony of his contemporary Pherekid, which is considered much less philosophical and more mythological, is fuller and freer to operate with all the elements at once, and therefore Thales still looks somewhat weak even for his time. If we believe Aristotle, the other reasons for choosing the water element are also taken from everyday observations.

- Dying organisms literally “dry up”;

- plants need water to grow;

- all food is soaked in juices;

- and all living things need water;

- and even the sperm of all creatures (the beginning of life) is moist.

His very life in the main commercial and maritime center of Greece simply had to inspire him with analogies to ships, and the opinion of the great role of water in the world. Such a life may well have inspired many of the astronomical and mathematical observations, for these sciences were then of an applied nature. From all that we know about Thales, he was most likely primarily an astronomer (as can be seen from the titles of his extant books, e.g. “Marine Astronomy”, ‘On the Equinox’).

So maybe the Neoplatonist Proclus was right when he reported that it was Thales who was the first Greek to start proving geometric theorems. Therein lies his main philosophical contribution. So, for example, Thales learned to determine the distance from the coast to the ship, for which he used the similarity of triangles. And according to one of the legends, being in Egypt, he amazed Pharaoh Amasis that he managed to establish exactly the height of the pyramid, having waited for the moment when the length of the shadow of a stick becomes equal to its height, after that he measured the length of the shadow of the pyramid and received its height. It is not accidental that even centuries after his death, in literary works the image of Thales was accompanied first of all by indications of astronomical interests, and his main attribute was a circlet. All this shows us that already in the time of Thales there were some rudiments of scientific, empirical, or practical approach to the matter. Here separately it is necessary to mention that according to Aristotle, except for a magnet Thales has found out attractive force of amber which is impossible to find out, without that to electrify amber by friction, for example about wool. Hence, Thales could conduct an experiment with electricity, and discover its magnetic properties. What conclusion Thales draws — we already know (motion = animatedness). But now we can assume that the action of the soul was directly connected with electricity. And it sounds already in spirit of modern images about Dr. Frankenstein. Certainly Thales hardly understood that deals exactly with electricity in our sense of this word, therefore his discovery had absolutely no value, neither theoretical, nor practical. But nevertheless we can say that we have before us the rudiments of the experimental method.

Thales’ hypothetical positions on philosophy

In the list of sayings of Thales, as a representative of the “Seven Sages”, there are philosophical lines. But they should be used very carefully, because a significant part of the heritage of the “sages” is a late antique fanfic. Here we may be interested in such statements:

The oldest of all things is god, for he is unborn.

The most beautiful is the cosmos, for it is God’s creation.

The greatest of all things is space, for it contains everything.

Fastest of all things is thought (nous), for it runs without stopping.

Strongest of all is necessity, for it overpowers all.

Wisest of all is time, for it reveals all.

…

When asked what is difficult, Thales answered, “to know oneself.”

To the question, what is deity — “that which has neither beginning nor end”.

To the question whether a man can secretly commit iniquity from the gods — “not only can he do it, but he cannot even conceive of it”.

We will assume that these statements could have belonged to Thales, and if so, we learn many new details here. It turns out that Thales thinks as a strict monotheistic philosopher, and asserts that God is not born (and probably not subject to changeability), he has neither beginning, nor end, and therefore most likely he is infinite. God clearly pervades the entire universe, and it is impossible to hide even his own thoughts from him. He has strictly determinized the world, for “necessity overpowers all.” And this world created by God is in an indeterminate state, because God seems to permeate it everywhere, but he is also its creator (hence, the world, unlike God, is created, and the existence of the world is not necessary for the existence of God himself; their identity in fact turns out to be quasi-identity). In a fragment from the “Refutation of All Heresies” of the writer Hippolytus there is a statement that, according to Thales:

Everything is formed from water by its solidification as well as evaporation. Everything floats on water, from which earthquakes, whirlwinds, and star movements occur.

This makes him the first author of the notion of the transformation of the elements by changing aggregate states. But the most interesting point is the recognition that space includes the concept of space, and objects are in that space. He explicitly derives this notion as a special “reservoir” for objects, and it is possible that he already implies emptiness here. This means that emptiness is also included in the definition of the nature of God. Why all this is significant, we will see next, through the example of Thales’ disciples and followers. But again, this is the most hypothetical part of his philosophical heritage, and it should be kept in mind.

Thales as a politician

To summarize his philosophical positions — Thales does not stand out at all from the thinking context of his epoch, he stands out only as a man who first voiced these ideas on the Greek cultural field, and with a claim to philosophy as a special kind of wisdom. All the strong points of Thales’ philosophy would be developed by his followers (including Pythagoras), and what is much more interesting in his story is that this “first philosopher” immediately shattered the notion that philosophy was incompatible with politics — i.e. practical and social activity. One of the popular fables about Thales tells how he foresaw a future harvest year, so he rented oil mills while the price was low, and then collected a huge income from the sales of olive oil. The story was meant to show that a wise man, if he wished, could easily acquire wealth that he did not need, and so wise men live in poverty of their own free will (this was a response to claims that philosophy is useless). But we also see in this an example that the image of the philosopher was easily incorporated into everyday practice. Most likely, Thales was a personal advisor to the ruler of Miletus; we even have information about two of his recommendations:

- In the first, he advises the 12 cities of Ionia to unite into a single federation, the center of which was to be the city of Theos. But this recommendation remained in the drafts.

- The second piece of advice concerned joining the coalition against Persia during the Lydian-Persian War. Thanks to Thales, Miletus was the only one who did not fight against the Persians, thus saving itself from destruction.

Even the most famous story in Thales’ life, namely the prediction of a lunar eclipse in 585, had significance on the scale of the entire Lydian state, directly affecting its fate, i.e. this event links him to political history. His ties to seafaring, his story of the oil trade, and his service to a tyrant of Miletus (and tyrants led the fight against the landed aristocracy) make Thales an economic progressive. But his statements as one of the Seven Wise Men — show him as a domestic conservative. In the context of his time, it is still worth considering him as a progressive thinker, given that he made a great contribution to the establishment of philosophy and popularization of Eastern knowledge.

In the end, it turns out that Thales is a court counselor, astronomer, and navigator who believes in mythological ideas about souls and promotes a prototype of monotheistic religion. A conservative in socio-cultural views, but a progressive thinker overall. He is of Phoenician rather than Greek descent, and his main historical achievement and contribution was the development of geometry. All of this is somewhat different from the image that has already managed to be stereotyped.

Anaximander and his Apeiron

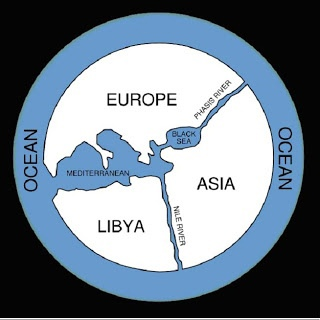

A disciple of Thales named Anaximander (610-546 B.C.) was also no stranger to social and political activity. It is known, for example, that he led the eviction of people to another Black Sea colony called Apollonia (today’s Sozopol in Bulgaria). But as a philosopher he is known primarily for being one of the first to write in prose, and for creating the first known map of the world; although this is more geography and literature than philosophy. At least two of the four known titles of Anaximander’s works (On Nature, Map of the Earth, Globe, On the Fixed Stars) suggest that the basis of his work, like that of Thales, was astronomy, and it is likely that it also had applications for sea travel. It is even possible that it was the fruit of their joint labors. It is believed that Anaximander wrote his works not just in prose, but in flamboyant prose, which gave away his love of all things luxurious. Thus, for example, it is said that he aspired to theatrical posture and dressed up in pompous clothes on purpose.

Anaximander (like Thales), borrowed much from the Near East, especially in matters of cosmology and the numerical calculations that depend on it. From astronomical achievements it can already be noted that Anaximander considered the Sun and the Moon larger in size than the Earth, and had a whole theory of lunar and solar eclipses, although again, some sources attribute these achievements to Thales. But it is undoubtedly Anaximander who is credited with the creation of astronomical instruments, particularly the gnomon, as well as models of the celestial sphere (i.e., the globe). And if Thales was evaluated by descendants as a “predictor of eclipses”, then Anaximander over and above this allegedly predicted an entire earthquake.

Speaking of Anaximander’s natural philosophy in detail, he believed that «the beginning of all things is apeiron. It is neither water, nor earth, nor air. It is nothing but matter itself.» This mysterious word is translated literally as “infinite” (or “limitless”), so we can consider that Anaximander’s universe is infinite. Apeiron itself is also indestructible, eternal, not created by anyone, and, most likely, also qualityless. As Epicureans, we are attracted by the fact that such a set of characteristics makes apeiron almost a complete analog of the atomistic theory, with the only difference that apeiron was not concretized as “the smallest particle” (and can be perceived as spatially infinite “matter as such”). Perhaps this happened because Anaximander did not even imply the existence of absolute emptiness; or perhaps simply because it is extremely poorly preserved for us. At least emptiness can be easily deduced from his theory on its own, which means that it was not something impossible, especially since other parts of his philosophical system, or Thales’ possible ideas about space in the cosmos, hint at it. On the other hand, apeiron can also be considered within the framework of the continuum theory. The set of its properties is quite consistent with the ideas of God as a Whole; besides, there is a lot of evidence in favor of this version. And among the hypothetical expressions of Thales we find that God had the quality of the infinite.

What is this magic apeiron, from which everything in the world is born? One can imagine many things, but there are only a few basic versions: (1) it is a pantheistic idea of God-Nature, who, having all the attributes of divinity, “creates from himself” our visible world; (2) or, following Aristotle’s version, it is not a qualityless prime matter, but a banal “mixture” of all elements, which would later be used by such philosophers as Empedocles and Anaxagoras; (3) or, more likely, both are true, that it is both a divine nature and a “mixture of elements” that the deity has produced “in himself.” From this may arise the notion of dualism, which was expressed in the words of Anaximander “the parts change while the whole is unchanging”. The analysis of what happens in the material apeiron (in the parts) is naturphilosophy, and the analysis of what happens in the original apeiron (in the whole) is theology. At the same time, it is obvious that naturphilosophy must be subordinate to theology. One can argue about these versions, it is no longer possible to prove anything for sure. Therefore, many will insist that Anaximander is the purest materialist. However, in such a case it would be strange that his followers do not pay any attention to this and develop his ideas in a theological way (e.g. Xenophanes).

Speaking about such an important category as motion, Anaximander believed that it is eternal, and that motion is even more ancient than moisture (and perhaps this is another property of apeiron). After all, it is due to motion that one thing is born and another perishes. And moreover, from this chain of reasoning Anaximander comes to the conclusion that the opposites (parts) united in it are separated from the one (the whole), and that the birth of things is not due to changes within the four elements (i.e. not by solidification or evaporation), but by means of their separation from this one. Of the opposites, the most basic are warm and cold, wet and dry. They influence the undefined “matter/apeiron”, resulting in different elements, combinations of substances, etc. The pair of dry and cold forms earth, wet and cold forms water, wet and hot forms air, dry and hot forms fire. Yes, it is possible to assume that here there is also a change of aggregate states of each of the elements, but this change also occurs due to the action of some of the opposites. In general, all world processes, which can only be imagined, occur due to the eternal movement of opposites. And here we have before us a ready-made theory of dialectics, which explains the principle of “motion as such”; and at the same time we have before us also a theory of determinism:

«From what all things derive their birth, to what they all return, following necessity. They all punish each other in due time for injustice.»

As far as the sources allow us to judge, apeiron is in rotational motion. If this is transferred to a single solar system, we can imagine how the mass of matter, due to this vortex motion, begins to stratify, and the heaviest of the elements (earth) is in the center, and the lightest — surround it with three rings. First comes water, then air, and then, as the lightest element, fire. Somewhere between air and fire, Anaximander depicts three spheres that cover the sky like an onion. In this conception, all visible celestial objects are essentially one object, i.e., celestial fire; and the only differences are that at different locations in the different “spheres” are different sized “holes” through which this light reaches us, in case the holes from the different spheres cross each other (these representations can also be found in Eastern cosmology). In this interpretation, celestial bodies for Anaximander are not even bodies at all, but only light, and then eclipses are the result of overlapping holes.

Geology and the theory of evolution in the system of Anaximander

Of some value is also the way in which he justified the immobility of the Earth. As mentioned above, he proceeds from the fact that the Earth is at the center of the world, which is proved by the vortex motions observed empirically in water and air. He transfers these observed motions to the whole world, and it turns out that the heavy elements are pulled toward the center of the world, and the heaviest element of the four basic elements was the earth. In addition, this explains why objects in the heavens revolve around us. Based on this premise, one could already understand why the earth is immobile; the center of the world automatically implies immobility. But Anaximander put forward an additional argument. For this purpose, he invented the principle of «no more this than that” — a principle actively adopted in the future by the atomists Democritus and Epicurus. Located at the very center of a strictly symmetrical universe, the Earth has no reason to move in one direction or another: up or down, in one direction or another. All directions are equally preferable, and therefore it is unrealistic to make a choice; there is no basis for a verdict as to why one direction is better than another. Hence, the Earth is stationary. And as we can see, it does not move for reasons of logical order, and is naively endowed with its own reasoning.

If we assume here that the earth is spherical, then the universe is also a sphere (and Anaximander is known as the compiler of some kind of “sphere” that was most likely a globe of the earth). The only thing that contradicts this is the vast amount of ancient evidence that Anaximander envisioned the earth as a cylinder, or drum, with two planes. In that case, the “no more this than that” argument loses its beauty. The contradiction here is on the face of it, and which interpretation is wrong, the sphere or the drum, is unknown. It may be a contradiction of Anaximander himself. But the contradictions do not end there. Despite his tendency to reason about the universe as an unchanging whole, Anaximander argued that the worlds (which for the Greeks was synonymous with the Galaxy) are many. In Augustine we find this passage:

«And these worlds … are then destroyed and then born again, with each of them existing for the time possible for it. And Anaximander in these matters leaves nothing to the divine mind.»

While Thales says quite differently: “mind is the deity of the universe”. Perhaps in this we can see the internal divisions of our conventional “school”, which does make Anaximander a more materialist-oriented thinker. This issue would later take center stage for the next generations of philosophers. Many will fall into confusion, and assume that the world (and on the universe) = god. Which means Anaximander is saying that gods can be born and die. Cicero and many others believed so (which is already more similar to Thales’ concept, but only allows for polytheism). But this view is opposed by writers such as Aecius, who defends Anaximander, and stands on the point of the inactivity of Anaximander’s “mind”. A perfectly reasonable assumption, especially since Cicero elsewhere tries to make almost all ancient thinkers (pan-)theists. But this does not in any way cancel the fact that Anaximander could be a pantheist within the whole universe, and consider the individual worlds as its numerous parts, which can be subject to change.

Worst of all, if the world and the universe were one and the same (i.e. if the plurality of worlds were not allowed), then the argument about the vortex motion of apeiron would work quite well. But now it turns out that all the above arguments about elements concern only a single world. The nature of apeiron now becomes unknown, and in what relation to each other are the worlds, whether they also move in a circle relative to some center — it is impossible to understand. All these contradictions and confusions will be solved by subsequent generations of philosophers.

And the most original development of Thales’ ideas was a completely new idea of Anaximander about the origin of life, and, in particular, the origin of man. In his account, the earth was originally completely covered with water, but the “heavenly fire” evaporated some of the moisture, lowered the sea level, and thus the earth emerged, and the vapor itself became the personification of the “element of air”, which also set in motion (air = motion = soul) the celestial objects. Here the transformations of the elements, beginning with water, come full circle. Thunder, lightning and storms were explained with the help of physics, where no mythological allegories with Zeus’ feathers were allowed, and stars were simply manifestations of a single fire. In such a scheme of spontaneous transformations, life originates somewhere on the boundary between earth and water (in a swamp). But even here Anaximander allows another contradiction, because in this case life arises only after the earth has emerged from under the water. But in separate passages he says that since originally there was no land, the first creatures were exclusively sea-dwellers, who only later had to adapt to life on land. And so even the first humans were fish. It turns out that life arises before the earth rose out of the water. So Anaximander has the first systematic ideas about the evolution of species. From the presentation of the elemental “cycle” of transformations it becomes clear to us why the philosopher represented consciousness, the human soul, in a very ordinary way, as a “water-like essence” (the element in its very essence represents movement).

Anaximenes and meteorology

The importance and further influence of Anaximander on posterity was enormous, far surpassing that of his teacher Thales, for two succeeding generations of philosophers drew from Anaximander. Alas, but the preservation of his works is too low, and this influence can be understood only indirectly, comparing the available passages with later authors. Still, we see that Anaximander’s system already contains all the later problematics, while he has these problematics relatively uncontradictorily united, and in his “apeiron” he was already one step away from atomism. The worse all this affects the evaluation of the subsequent representative of the “Milesian School”, who bears the name Anaximenes (approx. 585/560 — 525/502 B.C.), who already looks mediocre and weak against the background. Most likely he still caught the living Anaximander and even was directly trained by him. All sources agree that the main difference between the two is that Anaximander’s apeiron acquired qualitative certainty as the element of air. And that all further arguments almost completely duplicate Anaximander, including even the idea of cosmic spheres and the nature of stars. There is no way we can agree with this. Therefore, having depicted all the similarities, we will emphasize the more important, the differences.

In general, Anaximenes reduced all causes to the limitless (apeiron) air. The reasons why he did this can be different. For example, speaking about the question of motion, Anaximenes directly continued the logic of his predecessors, following Anaximander he recognizes air as a kind of allegory of motion, and from him he borrows the thesis that motion is more important and older than all other origins. But if so, then motion = air, and so it is the first element, which by its property is infinite. This reasoning may directly stem from a consistent reading of Anaximander. Besides, air could have been chosen because of a more universal and convenient explanation of phenomena of a complex order, the same questions of animation of bodies, their movement (there is no need to invent how the soul and movement arose, if these are already properties of air, which is the basis of everything). It is not clear, of course, why he did not like Anaximander’s universalism, but going back to the elements, the choice of air seems a very logical step.

«Just as our soul, being air, binds each one of us together, so breath and air encompass the whole of creation.»

Speaking of the cosmos, here Anaximenes also has a few refinements to Anaximander’s system. For example, there is only one cosmic sphere (not three), and it is an ice wall with fire leaves attached to it (not holes drilled in it). Like our earth itself, the cosmic objects are flat like leaves, which is what allows them to float in the air. If the principle remains the same (flat circles on an invisible sphere far above), the explanation is already somewhat different. In addition, Anaximenes stated that the Sun and Moon are of a special nature; that they are burning blocks of earth that are lower than the sphere of stars (according to Anaximander it is the stars that are on a lower tier). So it can be said that Anaximenes was more accurate in his teaching. This can be suspected even in terms of the stylistics of their writings. Readers complained that, unlike the “pretentious” Anaximander, he wrote very dry prose without artistic embellishments.

However, despite all this “scientificity”, according to Anaximenes, air is a god (Aecius, who had already defended Anaximander’s atheism before, calls to understand also under this “god” — the forces pervading the elements and bodies). The fact that air pervades the whole world and animates it, quite logically leads to the conclusion that it is God, in this we can see a clear borrowing of Thales’ ideas. As we said above, it is quite possible that apeiron was a god for Anaximander. Following his predecessors, Anaximenes considers motion as eternal; thanks to it all things turn into each other. But he entered the history of philosophy by the fact that, unlike his predecessors, the element of air is distinguished by the density or rarefaction of its essence. At rarefaction fire is born, and at densification — wind, then fog, water, earth, stone. And from this everything else already arises. From the degree of “thickening” its substance can change several times in succession, but at all stages it is the same substance. Even in the form of earth, air remains air. This is not a cycle of transformations of the four elements, but as if to postulate air as some special element standing above and including them all. It is also the first detailed expression of the idea of the transition of quantitative changes into qualitative differences.

“Out of air, when it is condensed, fog is formed, and when still more condensed, water is formed; still more condensed, air becomes earth, and the greatest condensation turns it into stones.”

Of course, we observe the transition of aggregate states even in Thales (not to mention Anaximander, where this view is also present). His predecessors, too, used opposites to explain such transitions. One significant difference here is that Anaximenes does not want to recognize “dry and wet” or “warm and cold” as substantively important elements from which the elements are generated. It seems absurd to him, because it should be just the opposite, such properties are consequences of material elements, not their cause (of course, if apeiron was a qualityless matter, then it also had consequences of the material substrate, but Anaximenes has already rejected pure apeiron). In this respect Anaximenes is even more materialistic than his predecessors. His pair of opposites concerns the properties of matter itself, not the effect we evaluate with the senses.

Here we may suspect that Anaximander also knew this, for he believed that the earth is heavier than fire; Anaximenes literally explains why this is so. Therefore, either Anaximander could also have used a similar explanation, or he proceeded from trivial obviousness without offering an explanation. In the latter case, Anaximenes made a significant addition explaining the difference in the weight of the four elements. More importantly, in order for the density of matter to change, we must allow for its porosity, some semblance of “emptiness,” the displacement of which increases the density. Although it is impossible to prove this with precision, Anaximenes is at least in extreme proximity to the discovery of elementary particles and the void. Certainly such detail helps to interpret meteorological phenomena more correctly. Anaximenes himself is considered primarily a meteorologist. That is, he explained all the phenomena of nature; not only thunder, lightning and hail, but also, for example, the phenomenon of rainbows and the causes of earthquakes.

So, speaking about the “secondary character” of Anaximenes, we cannot condemn the pupil of Thales and Anaximander for a huge number of borrowings, for he was their pupil. This is not surprising at all, especially since he introduced a number of innovations. What is surprising here is that he even needed to return to the level of Thales’ ideas, choosing one of the four elements as the central one, and talking about “divine Providence”. And yet, with that said, it is believed that it was Anaximenes who directly influenced philosophers such as Anaxagoras, Diogenes of Apollonia, and even the atomists. Therefore, it cannot be said that he was secondary within the Milesian school.

The Milesian school taken as a whole

Since we are already talking about the “Milesian” school, it is worth remembering about Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 535-476 BC), who was even scolded by Heraclitus in his time, accusing him of stupidity along with Xenophanes and Pythagoras. This Hecataeus was an active politician who participated in the Ionian revolt against the Persians, and was also almost the same age as Parmenides. The sphere of his professional activity was history and geography (he improved the map of the world created by Anaximander); and until the appearance of Herodotus’ “History”, it was Hecataeus who was considered the best of the authors on this subject. Like the rest of his contemporaries, including Heraclitus, he was most likely extremely arrogant, since the phrase: “I write this as it seems to me true, for the accounts of the Hellenes are manifold and ridiculous, as it seems to me”. That said, almost all of his writings are heavily influenced by mythology; he even engaged in a critical evaluation of mythology, attempting to “ground” that very mythology.

If the myth says that King Egypt and 50 of his sons came to Argos, Hecateus says: “Egypt himself did not come to Argos, but only his sons, who, as Hesiod composed, were fifty, but as I think, there were not even twenty”; and when it was necessary to explain what Cerberus was, he decided that it was a snake, and also began to diminish the scale of mythological pathos: “I think that this snake was not so big and not huge, but [just] scarier than other snakes, and therefore Eurystheus ordered [to bring her], thinking that it is not possible to approach it”. Skepticism as a methodological principle is evident throughout. Not so big, not so much, etc. If someone would say that the pyramids in Egypt are huge, here too, Hecateus would probably say that they are not so huge since ordinary people were able to build them. The subject of geography, the occupation of politics, the scientific approach to business — all this we have already seen above, and it is possible that Hecateus did not pass by the philosophers of his city, and is also worthy to be considered part of the “Milesian school” of philosophy. In addition to Hecataeus, the life of Cadmus of Miletus, another historian-logographer, who, like Anaximander, was regarded as the progenitor of literary prose, was around the same time. He wrote “The Founding of Miletus and All Ionia” in 4 books, and because of his name was later considered the man who adapted the Phoenician alphabet to Greek (the mythology of a hero named Cadmus is known to speak of this). But because of the connection with the mythological character, there are reasons to doubt that Cadmus existed at all. The noble families of Miletus often painted themselves as descendants of the Phoenician Cadmus, and this character may simply be an attempt to justify that “that” Cadmus was a resident of this city.

Besides Cadmus, one more woman can be attributed to the “Milesian” school, in connection with which there are also few convincing arguments, but nevertheless, it is worth to mention it so that the article about the “Milesian” school would be as exhaustive as possible. Cleobulina of Rhodes, daughter of the tyrant of Rhodes Cleobulus, one of the “Seven Sages”, became famous as a poetess and compiler of riddles. In some sources (Plutarch) she is considered to be a “companion” of Thales, which means that it can also be considered that she was significantly influenced by Milesian philosophy. Plutarch even wrote that Thales characterized her as a woman with the mind of a statesman. But Laertes generally claimed that she was the mother of Thales, which is not at all plausible, but at least confirms that her name was perceived as part of the story of Thales.

All distinctions made by us between Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes can be made only on the basis of very scarce extant materials. Most likely, all philosophers of this school complement each other, and everything that Thales and Anaximander knew was also present in some form in Anaximenes (even if it is not directly in the fragments that have survived). Conversely, something of Anaximander’s ideas may have been shared by Thales. It is just that all this cannot be learned directly from the sources. If we consider the “Milesian School” taken as a whole, several common points can be traced here:

- Recognition of the elements as the beginning, which ideally, with maximum abstraction, reaches apeiron.

- The soul is the cause of motion, and it is almost the universal God Himself. Everything in the world is animated, because the whole world is in motion (and the whole world is in motion, because everything is animated).

- Motion (= soul?) is the result of various opposites making the transition from one to another, and this motion is eternal. Contradictions are distinguished from unity, for in reality the world in the Whole is one.

- In addition to the unity of opposites, Anaximander has the idea of “Whole and parts” where all changes occur in the parts. In other words, in spite of all this struggle of opposites within the universe, it still remains “as a whole” the same as it was, nothing is added to it.

Here we see all the necessary ideas for an exhaustive understanding of the next generation of philosophers. For as it is said — “nothing arises from nothing”.

Добавить комментарий