The scale of the catastrophe for ancient literature

Not everything of ancient literature has survived, it is a well-known fact; and even the little that has survived has not always been preserved in its complete form. We know a great many names of ancient authors from whom we have not a single line; but even of those authors whose works have survived and are considered “classics” today, in most cases not everything has survived. Thus, of the numerous poets in the genre of Greek tragedy known to us today by name, only three of the most prominent — Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides — have survived as complete works; at the same time, only 7 (or 7.8%) of the 90 plays of Aeschylus have survived in full, 7 (or 5.7%) of the 123 dramas of Sophocles, and 19 (or 20.7%) of the 92 works of Euripides. In total, out of 305 plays by only three authors, albeit extremely talented, only 33 works, or 10.8%, have survived. And this is with such prominent names! One can only imagine how many thousands of plays were written by their lifetime contemporaries alone.

The same applies to the comedy genre. Of the 40 works of the famous comedian Aristophanes only 11 plays (or 27.5%) have survived. This is a very large index of preservation, against the background of tragedians, but the fact is that Aristophanes is the only comediographer in general anyhow preserved, while by name we know at least two more of his contemporaries, which later Alexandrian criticism put on a par with Aristophanes, and sometimes even higher. But even the recognition of the critics left no chance of preservation for them.

Already here it would be worth suspecting that if the famous people have reached our times in such a bad condition, it means that the “average situation in the ward” was much worse. According to approximate calculations, we know the names of about 2000 authors who wrote in Greek before 500 AD (before the conditional fall of the Western Roman Empire). And these are only the known ones! At least in some form, the texts of 253 of them (or 12.7%) have been preserved, and those, for the most part, are fragmentary, in quotations or extracts. So often there is not even a page of text. Similarly, we know the names of 772 Latin-speaking authors who lived before 500, but the texts of only 144 of them (18.7%) have survived. Taken as a whole (397 out of 2772 authors), this is only 14.3% of the potential for ancient literature. It should be borne in mind that this calculation is based on the names of authors; and as we have just seen, on the example of the four largest authors, even they were preserved by about 10-15%, what to speak of secondary authors, from which there are only a few passages or nothing at all?

Let’s assume for example, although it is not true, that 10% of their written heritage would have survived from each author; even this extremely insignificant value would have amounted to 3.6% of the total amount of literature that could have reached us. And that is only if all the authors had been preserved with the same zeal with which Sophocles was preserved. But, since the minor authors were preserved so poorly that simply nothing has survived from them, it is safe to assume that only of the known names of authors and the titles of their works, +/- about 1% of the entire heritage has survived from antiquity to our time; and how many authors remained completely unknown even by name — we can only guess.

More striking examples: Menander — the most famous comedy writer of antiquity during the so-called “Hellenistic” period, an incredibly popular author even in late Rome — but by the end of the 19th century he was already considered completely lost. Even after the incredible discoveries of the 20th century, only 7 of his 108 comedies have survived, of which most have survived about half, and only one comedy, “The Misanthrope” has survived in its entirety. Just one comedy out of 108 works! And this is the most popular author in antiquity. No less popular in his time philosopher Epicurus — wrote about 300 works, and from them only 3 letters and a hundred small excerpts have survived. Chrysippus — a Stoic philosopher, of whose 705 works not a single one has survived (although the excerpts will accumulate to 2-3 books in the format of ancient sizes). The same Democritus, whose collection of works existed in the first centuries of the Empire, a century after the last mention completely disappears. And similar situations can be counted in dozens! Only a small part of the list is available, for example, on Wikipedia.

Antique Libraries

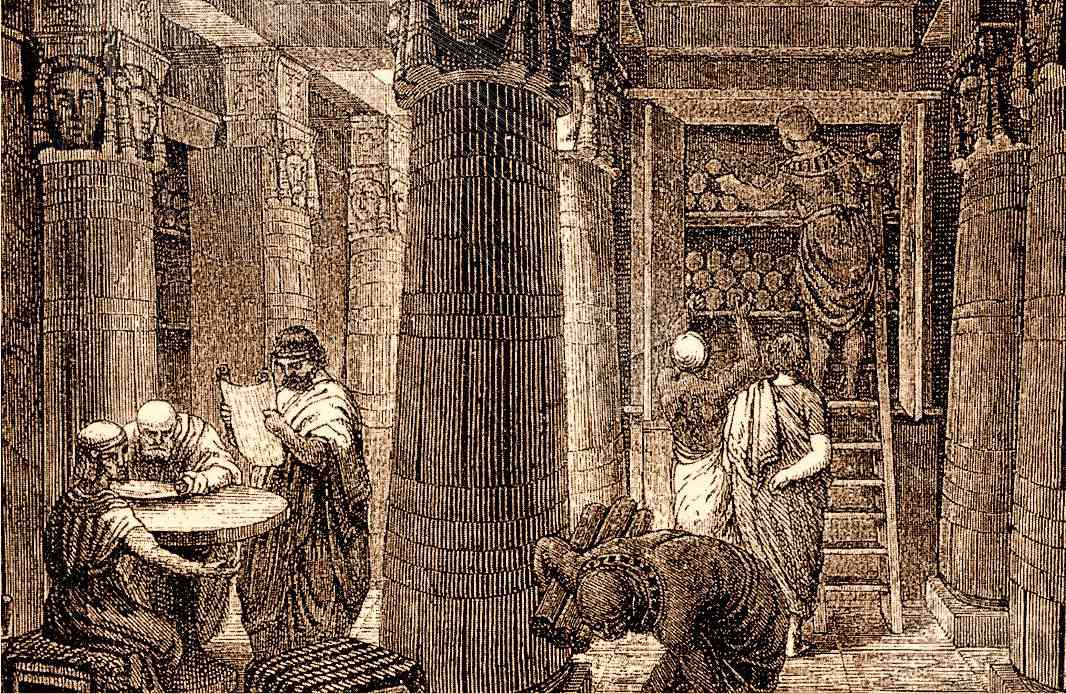

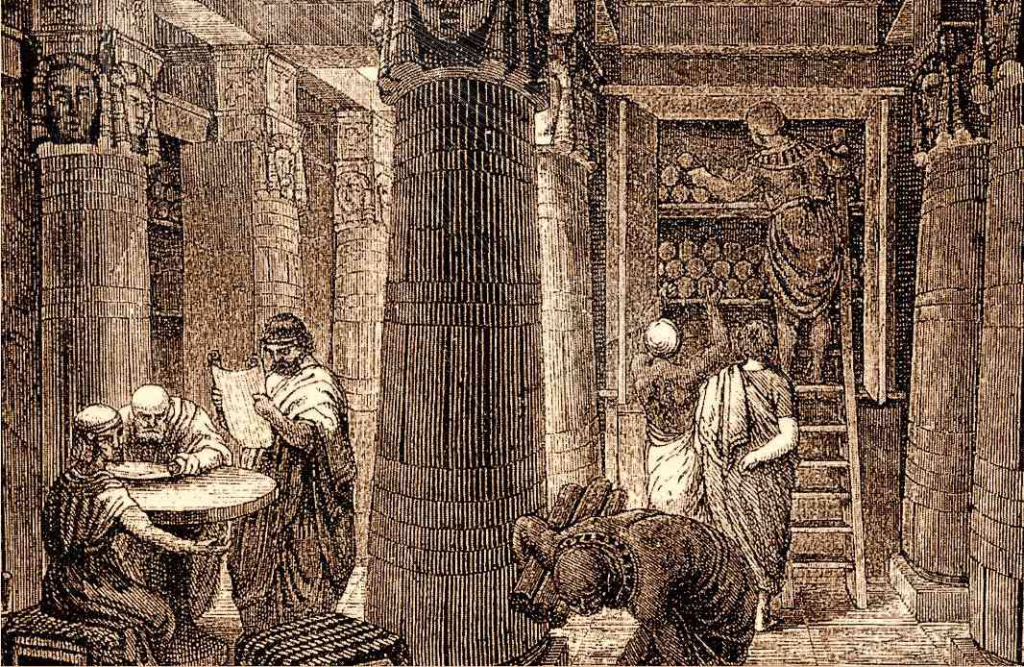

The number of libraries in antiquity was also quite large. The largest in the ancient world was the well-known Library of Alexandria, which included, according to various estimates, from 400,000 to 700,000 scrolls, mostly in Greek. Some modern scholars believe this number is overestimated and give another estimate — from 10 to 50 thousand scrolls. But even this figure looks quite impressive. The needs of intellectuals for books led to the transcription of at least 1100 scrolls a year (which means 50 years of work to reproduce the scale of the Library of Alexandria alone, and that is underestimated).

The volume of Latin literature was apparently comparable to the scale of the Greek world. In Rome, closer to the 3rd century AD there were large state public libraries supported by the emperors. There were 28 such libraries in all; each had two sections, Latin and Greek. And that’s not counting the numerous private libraries. One of the last mentions of public imperial libraries can be found in the edict of Emperor Valentus from 372 “On Antiquaries and Keepers of the Library of Constantinople”. The edict appointed four Greek and three Latin specialists in the restoration and copying of ancient books. In the capital of the eastern part of the empire, i.e. Constantinople, even in the fifth century, on the eve of the collapse of the west and the invasion of Atilla, the imperial library included 120,000 books. But the problems began after the so-called “Crisis of the 3rd century”. The decline of interest in scholarship and libraries in 4th century Rome was witnessed by Ammianus Marcellinus, who stated that “libraries are like cemeteries”. The civil wars of the late Empire and the barbarian invasions of 410 and 455 seriously damaged Roman libraries. According to a single mention by Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Gaul (Ep., IX, 16), one of the Roman imperial libraries was still functioning in the 470s, the last years of the Western Roman Empire. As a result of this desolation and the cessation of interest in the sciences, by the sixth century — by the time of Cassiodorus’ work — books had already become rare in Italy.

It is a little more difficult to determine the scale of private libraries, since tradition has preserved only occasional names of owners of large book collections. The size of these collections was sometimes exceptionally large, and could be compared to the libraries of the capital: a certain grammarian Epaphroditus (mentioned in the “Judgment”) compiled a library of 30,000 scrolls. The collection of Tirannion (Strabo’s teacher) was about the same size. At the beginning of the 3rd century AD, the physician Serenus Sammonicus collected 62,000 scrolls, and his son gave them to the younger Gordianus. Such libraries are quite comparable to the legendary libraries at Pergamum and Alexandria. But only one single integral library has survived to our days — in a villa in Herculaneum; and it stored, according to different calculations, from 800 to 1800 scrolls, mostly Greek and related to the philosophy of Epicureanism.

I.e. in the 3 private libraries mentioned above alone there was about 100 times more material than in the extant Herculaneum (about the same 1% preservation rate), which even so is considered an incredibly valuable find, with many fundamentally new sources. And how many other private libraries existed that we don’t realize existed? And how many more of the 28 public imperial libraries kept? Of course, the same editions must have been frequently repeated there, and yet the scale of the loss is quite estimable.

Materials and Causes of Disappearance

As can be seen from what we have said above, the centuries-long literary production of antiquity was very large, and the works that have survived to us in their entirety constitute a tiny part of it. The decisive role in this process played not only a simple historical accident. An ancient book could not lie for centuries due to the fact that the writing material was Egyptian papyrus, starting from the VII century BC. In the climatic conditions of Europe, papyrus scrolls wore out rather quickly: already in antiquity it was considered that a book-scroll older than 200 years was a great rarity. By the II-I century B.C., animal skin parchment began to compete with papyrus; but the parchment book (the so-called “codex” in the familiar book form) displaced the papyrus scroll only during the transition to the Middle Ages. In its bulk, the composition of the surviving monuments is the result of successive selections made (both in antiquity itself and at the beginning of the Middle Ages) by a number of generations who preserved from the literary heritage of the past only that which continued to arouse interest. An antique text written on papyrus could be preserved only if it was copied from time to time. And what is characteristic, monuments of ancient pagan culture were transcribed on papyrus scrolls, and new — Christian books were written on parchment codices. This created additional conditions for pagan knowledge to gradually disappear, even without any barbaric burnings. This point is also interesting because we can overestimate the negative influence of Christianity in the times of IV-VII centuries, when papyri, which had already decayed by the time of the Renaissance, could still be in circulation.

According to Italian finds, codices were not yet widespread until the 3rd century A.D., when the crisis came. But somewhere from the year 400, the codex became the only form of book, and up to the year 800, there was a gradual increase in the number of books produced. Just in the period from 400 to 800 most of the manuscripts had religious content; and in the sixth and seventh centuries secular works were probably not copied at all. The originals had decayed, and as a result, when interest in ancient literature began to return in Christian Europe, it was already hard to find. A study of Codices Latini Antiquiores conducted in the 20th century found, among other things, that not a single complete Latin manuscript created before the middle of the 4th century has survived. Only fragments, mostly papyrus, found as a result of archaeological excavations have survived. Works unpopular in the fourth to fifth centuries (including Christian works) have been largely lost.

In some cases, works that were lost in antiquity may have survived by chance; finds of this kind have begun to appear since the 19th century in connection with the discovery of papyri in Egypt (Aristotle’s «Politics of Athens» was discovered in this way). In the last 50 years, a large number of papyrus fragments from the Hellenistic and Roman eras have been discovered here; most are documents, letters, etc., but some contain literary material. Although there are very few scrolls with complete works among these papyri, and they are usually insignificant scraps, the papyrus finds are every year enriching our knowledge of ancient literature, especially in those areas that suffered from Late Antique selection. But what is particularly characteristic is that the increment of material delivered by the papyri relates almost exclusively to Greek texts; works of Roman literature rarely reached southern Egypt. And this illustrates once again the fundamental nature of the Latin-Greek division of the Empire itself.

With regard to fiction, the selection made in late antiquity was based mainly on the needs of the school, which taught literary language and stylistic art. The school for its own purposes selected the most outstanding writers of the past, and preserved their works, but usually not in the form of a complete collection of works, but only individual works, the best examples. In this “selection” from the classics of literature, certain branches and even whole epochs could fall out of the sphere of school interests, and this circumstance strongly affected the composition of the extant monuments. Greek lyrics, the literature of the Hellenistic period, and early Roman literature suffered particularly.

The amount of what was lost increased with the centuries, especially due to the sharp decline in the cultural level during the demise of ancient society. Meanwhile, it was this era, when papyrus scrolls were transcribed onto parchment, more durable in European conditions, that was crucial to the continued preservation of the monuments of ancient literature. The antique texts that survived in the first centuries of the Middle Ages have overwhelmingly survived to our time, as interest in them began to grow considerably from the 9th century AD. But even here, however, not all is well. For example, the “Library” of Patriarch Photius (IX century) contained abstracts of 279 works, but almost half of them have not reached our days. Therefore, let us repeat our conclusion once again: we can safely consider that only of the known names and titles of the works of antiquity have reached us +/- about 1% of the entire heritage; and how many authors remained completely unknown even by name — remains only a guess.