Xenophonte on the “Enlightened Monarch” (Cyropaedia, Hiero, Agesilaus)

In this paper we will combine reviews of several works by Xenophon because they are all linked by one conceptual theme — the education of the ruler. This theme is presented in three ways. In the historical novel “Cyropaedia” the best example is given, where they show an idealized Persian monarch, his growth from childhood to the deepest old age. In the panegyric on the death of Xenophon’s friend and patron, the king of Sparta named “Agesilaus” — show a rather more formed ideal, without its long formation, but the essence is about the same. By looking at Agesilaus, we can learn something useful. Well and the dialog “Hiero”, about the disadvantages of tyranny, where the protagonist is a man already formed into a tyrant, but who still suffers from his position and would like to change for the better. He is given instructions that he never takes advantage of. But we consider it in the same series of essays, because admonitions to the monarch for his improvement are, in principle, also part of the general theme of “education of the ruler” and “enlightened monarch.”

Immediately it is worth saying that in terms of content the most interesting will be “Hiero”, so we recommend going straight to it. “Agesilaus” appears here rather for statistics, because the work is very secondary, but ‘Cyropaedia’, although it is the most significant work in this list, is a very voluminous work, and reading its description will be no less tedious than reading the original.

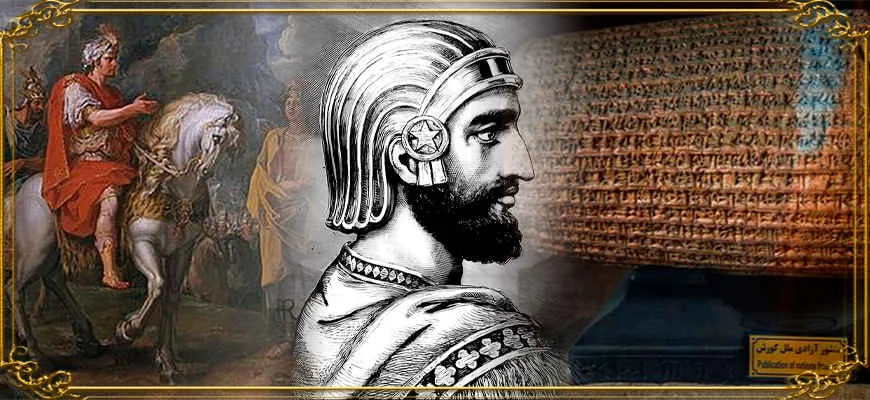

Cyropedia — a success story

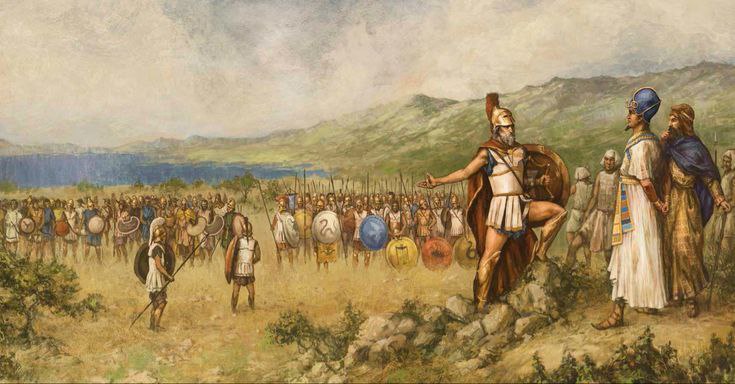

One of the first works in world literature devoted to the theme of educating an “enlightened monarch” is Xenophonte’s Cyropaedia. Given that the author of the work was Greek, it is particularly interesting that this monarch is Persian. Especially since, as a rule, pro-Spartan Greeks and lovers of aristocracy (and Xenophontes was such) opposed Persia in order to shift internal squabbles to an external enemy, while increasing the importance of the land army, while democrats showed loyalty to Persia as a profitable market. But here the opposite is happening. Of course, this is partly due to the fact that already at the end of the Peloponnesian War, following the “divide and rule” policy, Persia helped Sparta to defeat Athens and become a hegemon; and partly due to the fact that Xenophontes himself fought in the intra-Persian wars on the side of one of the princes (see “Anabasis”).

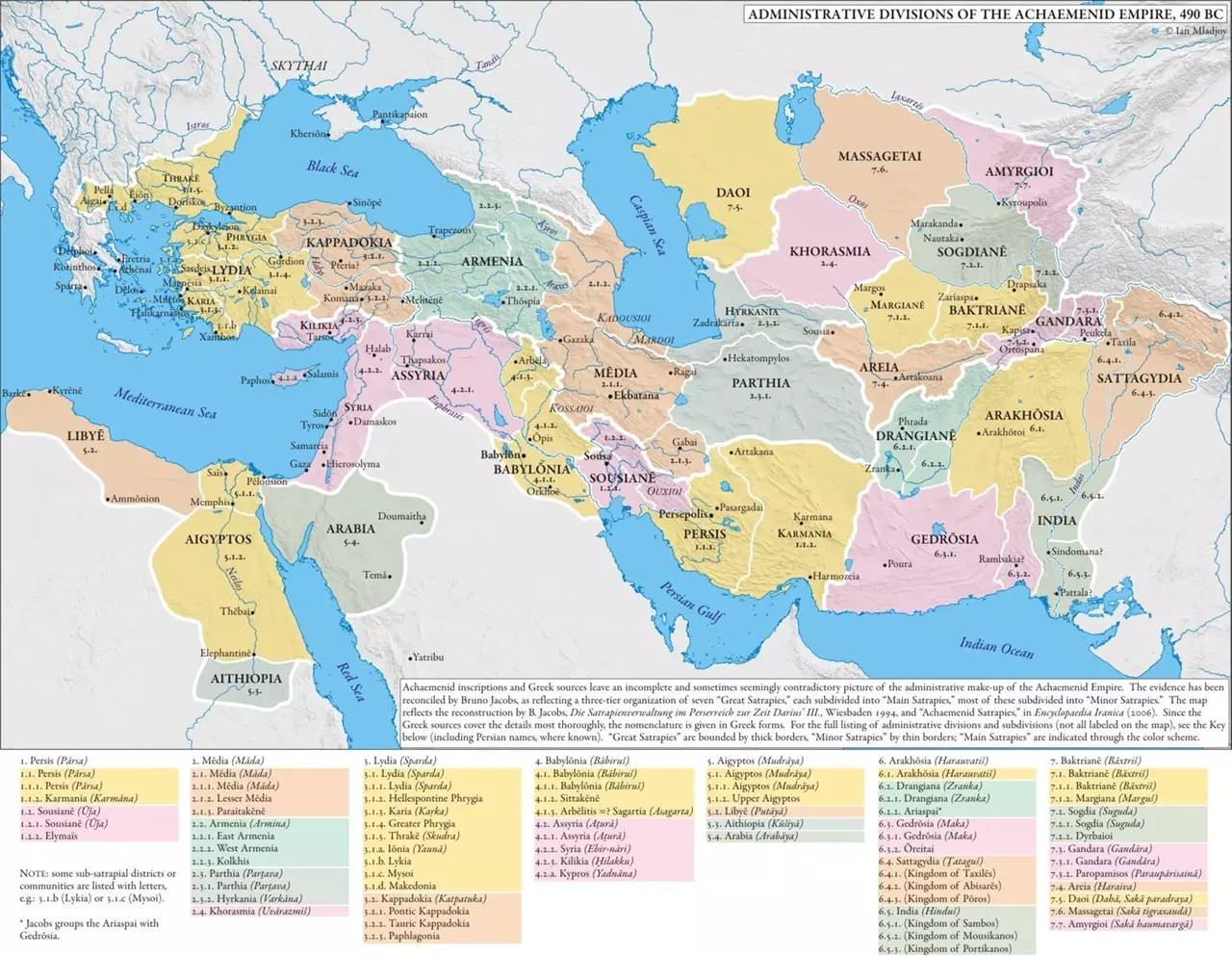

No matter how Xenophontus viewed modern Persia, at least at the time of its foundation, it was an excellent country, where aristocrats ruled, the refusal of luxury was cultivated (in the ruling classes), agricultural traditions were inculcated, etc. (he speaks about it in his work “Oeconomicus”). In a sense, Persia is painted as the same Sparta, but only of enormous size. The main achievement of Persia was that its monarch was subjected to people from the most diverse nations and cultures, without having the opportunity to see in person the king they served. He deliberately emphasizes that all countries of the world have a national character, whereas Persia is a multinational empire. This degree of “voluntary” submission to kings is, in Xenophon’s eyes, the main reason to admire their polity; unlike them, the Greeks can hardly be forced to obey even a man they know well. That is why “Cyropaedia” begins with a comparison of the work of a shepherd and a monarch. Humans, unlike animals, are supposedly very willful, and do not want to obey; they rebel at the first convenient reason.

On the basis of all this we thought that it is much easier for man to establish his dominance over all other living beings than over humans. But after learning about the life of Cyrus the Persian, who became the ruler of many subordinate people, states and nations, we were forced to change our opinion and recognize that the establishment of power over people should not be considered a difficult or impossible enterprise, if you take it with knowledge.

Thanks to Cyrus we have learned that the difference between man and animal is not so great as it seems. Governing nations is like governing cattle. It is clear that the main focus of this novel (“Cyropaedia” is considered more of a literary work than a scientific-historical work) is on the upbringing of Cyrus, who will create this magnificent empire. Xenophonte wants to show us the way to create an ideal ruler, not just state the fact of Persia’s superiority over the rest of the states. But of course, it’s not just about upbringing, it’s also about Cyrus’ semi-divine ancestry (through lineage from the hero Perseus himself! That’s where the name of the state “Persia” comes from). The noble blood also does its work.

As it is said in tales and sung in the songs of barbarians, Cyrus was a young man of rare beauty; he was distinguished by extraordinary ambition and curiosity, could dare any feat and any danger to be exposed for the sake of glory.

The upbringing of children, at least among the elite, is very close to Spartan (once again: this is a novel, and here Xenophontus is trying to push his ideals, and in many ways they are Spartan). The Persian government quarter is deliberately cleansed of merchants so that “their coarse voices ‘ are not heard and so that the ’assembly” of these people “does not mingle with the noble and well-bred”. This beautiful place, in which only the “noble” live, is divided into four sections, according to age; and, as in Sparta, it is the old men who educate the young, because only they are able to educate the children in the best way. Of course, this education is of a paramilitary nature. And just as in Xenophon’s “Lacedaemonian Politics”, in Persia the ability to fulfill any orders of those in power as quickly as possible is valued.

Persian laws contain preventive measures and from the very beginning educate citizens so that they will never allow themselves a bad or shameful act.

If in Greece children go to school to learn literacy, in Persia they go to school to learn justice. Why these two things (literacy and justice) are opposed is not clear. But what is clear is that much of the time in Persian school takes place in show trials. Children are constantly being tried, similar to formal courts, for all their misdeeds. They are taught asceticism, patience for hunger and thirst, and basic archery and spear throwing skills. The principle of “respect your elders” plays a big role. And since all elders are role models, the children grow up to be perfect.

In adolescence, children begin to perform more formal service, reminiscent of the police, and occasionally participate in hunting parties organized for kings and aristocrats. Engaging in hunting only reinforces all the previously learned skills of the ascetic warrior. Basically, here we see everything the same as in the “Lacedaemonian Polity”, but in a slightly smoothed out form. In time, the teenager passes into the category of “mature husband”, who, in principle, continues to do all the same things as the teenager, but only even more professionally, in addition to learning to fight in close combat. But even the “mature husband” is cut off from the administration of the state. All administrative affairs fall to the elders, who no longer fight, but are exclusively engaged in administration. This is a kind of career ladder of 4 stages, which must be passed step by step (like the “magistracy” in Rome, only very poor and almost without changes in duties). But participation in this career ladder only applies to the aristocracy. Those who can’t put their children in public school, those people have their children at home, and most likely they will simply inherit their parents’ civilian profession.

Even to this day there are customs which testify to the moderation of their food and the care expended in digesting and assimilating it. Thus, in Persians it is considered indecent to spit and blow one‘s nose, to walk with a belly bloated with gas. It is considered disgraceful to leave in full view of everyone in order to urinate or for other natural needs. Persians may do so because they lead a moderate life and use up the moisture in their bodies in strenuous physical exertion, so that it finds its way out in other ways.

This is just a funny fragment, and Herodotus writes about the same things. It turns out that in Greece it was customary to urinate and piss in the street, if this is given as an example for the Greek reader. But the fact that Persians do not piss, but sweat, looks like some “meme” about princesses. Further this theme, i.e. constant exercise to go to the toilet less, will be heard many times.

In general, after such a description of the Persian education system, Xenophontus moves on to the prince Cyrus. Until he was 12 years old, Cyrus studied like all other children (only much better), until he had an audience with the king of Midia, his grandfather, who was very interested in his grandson’s success. After their meeting, Cyrus continued his education already at court, so it was a little different from the typical one. The main peculiarity of the situation was that his grandfather was a Musselman, while Cyrus himself was a Persian. At this time Persia was still only a small province of Mysia, and on this Xenophontus draws contrasts. The manners of King Astyages are much more depraved than those of the Persians, and so the king meets Cyrus in a luxurious purple robe with gold jewelry. And so when he gives a sumptuous lunch, little Cyrus will “involuntarily” start teaching his grandfather about manners:

— Does not this dinner seem to you much more sumptuous than that which the Persians have? — Astiag objected.

— No, grandfather, it does not. We reach satiety in a much simpler and shorter way than you do. It is customary for us to satisfy our hunger with bread and meat, while you strive for the same goal as we do, but you make many deviations on the way and, wandering in different directions, hardly come to the place where we have already come long ago.

And then Cyrus gives his grandfather a lesson in practical stoicism, giving all his meat to the servants for good service, and leaving himself nothing at all. The whole of Cyrus’ “education” is composed in such moralizing. We are demonstratively shown the difference between power based on law (Persians) and power based on the will of a tyrant (Midians), etc., etc. The Persians are always analogous to the Spartan Greeks. And it was only at the expense of Persian morals that Cyrus was able to achieve immense popularity at the Midean court. The poor Musselmen had never seen a man who was not a rusty brute, and they lined up for the advice of the ideal man. His only disadvantage, against the background of the Spartans, was only that he liked to talk a lot (but even this is here called forgivable). And the main reason for his success was his desire to achieve victories where you are weak, through stoic endurance (what is not another manual on business stoicism?).

Cyrus passed his test of courage in practice, during Assyria’s attack on their country. By making a reckless attack bordering on suicide, he was able to break a superior enemy. While this is usually condemned, here Xenophonte considers Cyrus’ act more of a good thing. The risk was rewarded (another success of business stoicism) and Cyrus became the most popular man in the country.

Cyrus returned home to his Persian province, already a star of statesmanlike proportions. The local Persians were picky in their attempts to convict him of moral decay, but he was quick to prove that his Spartan Persian disposition had hardly deteriorated after living in a luxurious palace. And while he was in Persia, news came from the capital that his grandfather had died, and his uncle, Kiaxar, became king. Taking advantage of the convenient moment, the king of Assyria created a coalition to destroy the Midians and Persians (the coalition included the legendary king Croesus). Thus began the great war that would determine which nation would form the basis of the Middle Eastern Empire. In this war, Cyrus became the leader of the army of the Persians as vassals on the side of Midia.

A great deal of space in the book is taken up by the theme of preparations for war, and the central place in which was religious piety and the search for favorable signals from the gods (if you take any work of Xenophontes, this theme will always occupy the first place in importance). For that time these things were rather commonplace, and therefore Xenophon is hardly distinguished as a conservative, especially in a work about history, if such a tradition was really observed. Therefore, the specific example that his father gives to Cyrus, which is essentially an argumentation of “Protestant ethics” (cf. even more vividly this ethics looks in the work “Oeconomicus”), is much more attractive:

Do you remember, my boy, how once I had this thought. After all, the gods have given people who are skillful in deeds a better life than those who are inept; the industrious ones are helped to reach their goals sooner than the inactive ones, the caring ones — to be more confident in their safety than the carefree ones. And since one must become exactly what one needs to be in order to succeed, it is only on this condition that one can appeal to the gods for any good.

Religious piety correlates directly with the behavior of a successful person, and vice versa (cf. Calvinism). Cyrus adds that it is pointless to ask the gods for a good harvest if you do not know how to cultivate the soil well, etc., etc. So it turns out that nothing really depends on the gods, they only give formal confirmation that you are good. And besides this example, the father gives another admonition to his son on the literal subject of the “enlightened monarch” and says that if any ruler :

… would be able to command other people, so that they would have everything they need in abundance and yet become what they should be, would this not seem to us in general the greatest feat, worthy of admiration and wonder?

That is, it turns out that a good ruler should show his quality in the welfare of his subordinates (see “Hiero”, the next section of the article), and most importantly, in the education of their morals (cf. European classicism, Plato’s ideals, etc.). But since Cyrus was to manage the army only, for the time being, this question turned to the military plane. And apart from the platitudes about providing everything in the best possible way: provisions with logistics, health and morale, equipment, etc., there is a funny moment where Cyrus intended to invite doctors into the army to take care of the sick. But it was his father who responded that doctors for the army were… well… fucking unnecessary:

The men you just mentioned are like craftsmen who mend tattered himati; after all, doctors only treat people when they get sick. A wise general would rather temper his warriors constantly, taking care of their health, than invite physicians. From the very beginning you should take measures to ensure that your army is not sick.

And the main recipe for maintaining health (except for choosing a place for the camp away from the swamps) is asceticism in food and physical training, because if you do not exercise, you will become lazy, and the lazy, as you know, necessarily eat more. So it turns out that without physical training the army will have problems with provisions. In Cyru’s opinion, to inspire others and lead them to the enemy, he has supposedly already learned. And not in spite of, but even thanks to the fact that he was brought up in total obedience to his elders. Allegedly it is after a life of subordination — you yourself get the knowledge of how to subdue others (the science of “obey and command” was considered the main science in Sparta). However, Cyrus’ father explains that this method is only the first stage, and the real subjugation can only be quite sincere, based on the belief in the superiority of the leader, i.e. the commander should just be the best of the best, and people will pull themselves.

After more instruction on strategy and tactics, Cyrus gets to the battlefield. Their army has 2.5 times fewer soldiers than the Assyrian Coalition, and of course they will win, overcoming such a minor difficulty. And of course virtue flourishes in their midst and they try to observe equality, if only in the division of booty and rations at common meals (but preferably also in duties). But it is also striking that Cyrus advises to create an army not only from fellow citizens, but from any worthy people at all. Another note of leftist egalitarianism in a traditional conservative text. And while Cyrus’ army, overcoming difficulties, defeated a stronger enemy, he himself was busy educating his soldiers. In addition to fostering a spirit of equality, he also fostered in them a hatred of hedonism, linking it to idleness and anti-social behavior:

And very often the vicious attract many more people than the honest. Lured by the pleasure provided immediately, vice in this way recruits a lot of like-minded people, while virtue, showing a steep path to the heights, is not too attractive in the present, so that it is followed without much thought, especially when others draw you down the sloping and seductive path of vice (cf. the tale of Heracles, allegedly authored by the sophist Prodicus, which is known only from Xenophontus). By the way, those who are bad by their laziness and carelessness, bring harm only by the fact that, like chickens, live at the expense of others. Those who shirk work and show extraordinary energy, shamelessly seeking to seize a greater share of benefits, more than others entice people to the path of vice, because by their example they prove that meanness is often profitable. From such men we must emphatically purge our army.

In other words, it is not at all surprising that Communists find the aristocratic and conservative literature of antiquity — their own base. This is yet another clear illustration in the spirit of “find 10 differences between right and left”.

In order not to prolong the narrative, we will skip the scene with the subjugation of Armenia, although there was a lot of conservative moralizing there too. Having exemplarily tried the king for treason, Cyrus made him his friend. But it is not only masculine virtues that should be the constant focus of attention. Xenophonte does not forget the female bondage of chastity. Thus, after a long scene of the king of Armenia being brought into submission, we are shown a dialog between his son and his wife:

When they arrived home, they spoke only of Cyrus: one extolled his wisdom, another his strength, another the meekness of his temper. There were others who praised his beauty and stateliness. Tigran asked his wife:

— Armenian princess, did you find Cyrus so handsome too?

— By Zeus,” she answered, ”I did not look at him at all.

— Who did you look at then?

— The one who said he’d give his life if he didn’t want to see me as a slave.

The perfect Cyrus, the perfect Tigran and the perfect Armenian wife. And the ideal Cyrus wins in many respects by his peace-loving policy, and the whole thing resembles the same sweet panegyric that was written to the Spartan king Agesilaus (see “Agesilaus”, section below). Having subjugated Armenia, Cyrus learned that it was suffering greatly from raids by mountain tribes of Chaldeans, and to secure the rear, he decided to deal with it. “They were employed by all who needed hired soldiers, for they were distinguished for their bravery and were poor, for their land was mountainous and infertile”. Cyrus defeated the Chaldeans in battle without much trouble, and showed the same humanism as the idealized Agesilaus in order to gain their trust, i.e. released all the captives and transferred the wounded to a hospital for treatment. However, even if this is another ideal picture that is not connected to reality, it is still interesting what Xenophontus considers his ideal. And here we see the principles of creating a strong confederation on economic grounds (a kind of European Union with the rudiments of UN peacekeepers). This is a very important fragment if we want to understand the economic logic of ancient Greek philosophers.

— Is it not because you Chaldeans want to make peace, that by taking possession of these mountains and making peace, we have made your lives, as you have now realized, safer than when the war was going on?

The Chaldeans answered in the affirmative, and Cyrus continued:

— And if you also receive other benefits by making peace?

— Then we would be even more pleased,” replied the Chaldeans.

— You are considered poor only because your lands are not fertile, are you not?

The Chaldeans also answered in the affirmative.

—So don’t you agree, — Cyrus then said, — to pay the same taxes as Armenians, if you are allowed to cultivate as much land in Armenia as you wish?

The Chaldeans responded to this proposal with consent, but only on condition that they would not be wronged. Then Cyrus addressed a question to the Armenian king:

— And you, Armenian king, do you agree that your now vacant lands should be cultivated by them on condition that they pay the taxes fixed by you?

— I would give a lot for this to be realized,” replied the king, ”because the state’s income would then increase much more.

—And you, Chaldeans, possessing beautiful mountains, will you allow Armenians to graze their flocks here if they pay you justly?

The Chaldeans agreed, for, according to them, they said, they would benefit greatlyfrom such an agreement , and without any additional labor.

— And you, the Armenian king, would you like to use the pastures of the Chaldeans on condition of paying a small sum to the Chaldeans, but receiving a great benefit?

— Very willingly, for I believe I shall graze my flocks in perfect safety.

— Surely you will feel safe when the mountains are your allies? — Cyrus asked.

The Armenian king agreed to this.

— But we are ready to swear by Zeus, — said the Chaldeans, — that we will have no peace, not only in the land of Armenians, but even in ours, if these mountains belong to them.

— And if the mountains are yours?

— Then we shall be sure of our safety.

— But, by Zeus, — said the Armenian king, — we will not be calm, if Chaldeans again occupy these peaks, and also fortified.

Then Cyrus said:

— So I will do as follows. I will not give any of you authority over these mountain peaks, and we will guard them ourselves. And if any of you commits an unjust act, we will take the side of the offended.

The Armenians and Chaldeans, hearing this decision, praised Cyrus and said that only on this condition the peace concluded between them would be lasting. At the same time they exchanged pledges of allegiance and made an agreement that both their peoples would be free and independent. Marriages between men and women of both nations were legalized, the right of mutual cultivation and grazing was established, and a defensive alliance was made in case either party was attacked from outside.

From interesting trivia: the ancients sacrificed not only to their gods, but also to the gods of the enemy, to lure them to their side and weaken the position of the enemy. This is what Cyrus did before the key battle of the first phase of the war. Without recounting the entire course of the battle, the Midians and Persians were able to defeat the coalition of Assyrians, and Cyrus decided to go in pursuit of the breakaway parts of the enemy’s general army, in the process gaining the support of some small states that were vassals of Assyria. The king of Midian remained in camp, fearing lest the pursuit end in defeat (and thus doomed Cyrus to glory, eventual victory, and Persian dominance). And having discovered in battles that the weakness of the Persian army was that it consisted mainly of infantry and could not cope without the Midian cavalry, Cyrus decides to create a cavalry in Persia itself (Xenophontes himself was of the horsemen class and very fond of cavalry, about which he wrote several special essays).

While the military campaign in Assyria is successful, Cyrus already has a considerable part of the empire under his rule, and we are given an arch-typical description of his behavior, following which he again releases prisoners and gains the support of the local population, and even the first Assyrian defector he trusts as his own brother and brings him into the circle of the high command. It is true that here it is tried to show us that he acts with naked calculation, and treats the whole subordinate population as potential “informal” slaves, but still with a very humane general discourse.

‘We must now take care of two things,’ said Cyrus, ‘first, to become stronger than the masters of this country; secondly, to keep the population of the country in its place. A land inhabited by people is the most valuable possession, and when it becomes deserted, it is also deprived of all its riches. I know,” added Cyrus, ”that you have slaughtered the enemies who resisted, and you have done the right thing; that is what makes a victory enduring. Those who have surrendered their weapons you have brought with you as prisoners. But if we let them go now, I believe it will also be good for us. Firstly, we shall not have to watch out for them and guard them; secondly, we shall not have to feed them, for otherwise we would not starve them! Then, if we let them go, we shall have many more prisoners. For when we take possession of this land, all those who live in it will be our prisoners. And when they see their fellow tribesmen unharmed and free, they would rather stay at home and be submissive than fight us.

Not to mention such qualities as knowing all his commanders by name, we are left to wonder whether Julius Caesar was really as humane and pansy towards his enemies and his own soldiers, or were these the same fictional stories and eulogies as those of Cyrus or Agesilaus? Or perhaps Cyrus, Agesilaus, and Caesar were all really like that? Or maybe only Caesar, because the information about him is the most reliable, with sources on both sides of the barricades? I don’t know. But the fact is that the image of the ruler-soldier, which draws Xenophontus, is popular in different eras, and similar features are attributed even to Napoleon Bonaparte.

And so, while Cyrus achieved success after success, the king of Midia slept and drank in the camp. And having sobered up, he suddenly learned that a considerable part of his army had left after Cyrus, who, without reporting anything and without asking permission (you bet, if the tsar was out of access), had gained the support of many fallen peoples, etc., etc. Because of which the tsar was very indignant and began to suspect the preparation of a coup. But Cyrus, of course, did not intend anything bad and was the embodiment of holiness itself, and so even the army of the Midians was heartily on his side. And how could they not be fans of the Persians, if for the umpteenth time, showing a picture of a camp-shelter, we are reminded of the hatred of hedonism:

As experienced riders do not get lost when sitting on a horse, and can see, hear and say what is necessary, so the Persians believe that at meals one should remain reasonable and observe the measure. And to enjoy eating and drinking is in their eyes an animal and even pig-like quality.

Once again, knowing perfectly well that there are many orders of magnitude more enemies, Cyrus decides to simply go straight ahead with the expectation of panic in the camp of the enemy, so he simply storms Babylon head-on, relying on the advice of a familiar nobleman from the ruling class of Assyria. Still, having achieved some successes, he does not dare to storm such a fortified city. Instead, he returns closer to the camp of Midian to talk to the king and reduce the degree of tension. At the meeting with Cyrus, the king cried, realizing his own alleged insignificance on his background. The tsar was very offended that all successes are made by Cyrus, but the perfect diplomatic abilities of the perfect in everything Cyrus allowed them, at least formally, to reconcile. Before the second round of the campaign, again on the initiative of Cyrus, begins a major reform of the army, the construction of new siege guns and new sickle chariots. From an ordinary war it turns into a frankly conquest war.

The reformed army of Cyrus was to be met by a new coalition, now led by the Lydian king Croesus and the Greeks of Asia Minor. All descriptions of the battles are, as usual, long and uninteresting. From the point of view of tactics here, as well as in general in almost all literature about the war, examples are simply ridiculous. With the pathos of a grandmaster of war, Cyrus tells us that it is better to put archers behind the infantrymen rather than in the front row; or that cavalry is better to hit the flanks and try to surround the enemy; or that too many rows in a formation makes the men in the back rows useless. It’s so basic and primitive that even a preschooler who first downloaded Total War can master it, but the ancient books on warfare repeatedly present it as something very wise. I never understood that… but I guess in a topic as dull as battles, you can’t write anything more interesting. Anyway, Cyrus won again, and again none of his friends died, so the children’s ride continues, and now the siege of Sardes and the capture of Asia Minor awaits him.

However, Sardes he took literally for 5 lines of text, and as usual, nothing robbed, did not take slaves, and the defeated king Croesus became his friend and adviser in the campaigns. And even at this point in Cyrus’ retinue, one of his comrades finally died, albeit of little importance to the plot. This man’s wife, having said that everything would be fine and that she would find somewhere else to go, lied to Cyrus, and commits suicide over her husband’s body. Drama a la classic Euripides. Finally, Cyrus has his first trouble in the entire narrative! Admittedly, by this point the book is nearing its finale. Having conquered a number of more countries and expanded the number of warriors, Cyrus has gone to Babylon. Supposedly, he now has not only a qualitative but also a numerical advantage. Whereas before he had taken candy from children, now he could surely beat up an infant. But the Babylonians hid behind the most powerful walls, and stocked up on provisions for 20 years of siege. The only way to take the city is by stealth. Now Xenophontus retells the story of how Cyrus, having dug two bypass channels, changed the course of the Euphrates River, which ran right through the city, and was able to pass along the old course right inside the city.

Cyrus himself also wanted to surround himself with such an environment, which in his opinion, befitted a king.

Having become a full-fledged king, in fact already an emperor, he explained to his friends why he would now have little time to socialize with them. He begins to behave like a typical king, fearing the revenge of the conquered peoples — he creates a personal guard and surrounds himself with eunuchs. Like the typical tyrant from the dialog “Hiero”, Cyrus tries to keep the Babylonians on the edge of poverty, so that they feel more vulnerable and cling more to his regal figure (although in this case it is not considered something bad). In essence, Cyrus becomes a tyrant, but Xenophon tries to present it as if “this is different”. Cyrus does everything sincerely and openly, and he himself is a good man. And since his friends approve of everything, it is not a “tyranny” at all, but a normal, naturally occurring monarchy.

Cyrus supposedly makes his ascetic ideals of a Spartan the standard of the state. Everyone believes that a monarch = a good father, and a good father keeps his family well off and his house in order. Of course, Cyrus makes religiosity the main pillar of society, believing it to be an excellent pillar for morality and mass obedience to the king. Here appears the basic model of functioning of the “enlightened monarch”: if the monarch is good, the society will be exemplary. Everything works through personal example and thirst for emulation by elites, and “bad” nations are the merits of bad monarchs.

In order to convert others to the constant observance of temperance, he considered it especially important to show that he himself was not distracted from good deeds by thepleasures always available, but on the contrary, before funpleasures, he strove to work for a lofty goal. Acting in this way, Cyrus achieved at his court strict order, when the worst hurried to give way to the best and all treated each other with courtesy and respect. One could not meet anyone there who expressed his anger with shouting and his joy with insolent laughter; on the contrary, observing these people, one could conclude that they really lived in accordance with high ideals.

All in all, on the throne, Cyrus simply reproduces the old Persian/Spartan orders on the scale of an entire empire. Educates obedience, chastity, modesty, religiosity, military spirit, etc. etc. etc. (in “Oeconomicus” he will add that in practice such a superhuman must also cultivate the land himself, also an important point for a valiant husband).

Cyrus’ opinion that a man should not rule unless he surpasses the valor of his subjects is sufficiently confirmed both by all the above examples and by the fact that, exercising his men in this way, he tempered himself with even greater care, becoming accustomed to temperance and mastering military techniques and exercises.

…

He educated them also to the habit of not spitting or blowing their nose in public, and not to turn around visibly at the sight of anyone, but to remain imperturbable. He believed that all this helps to appear in front of subordinates in a more honorable way 🧐.

There will be nothing further to recount in detail. It will just be a set of repetitions of what has already been said. We were shown that the only threat to him were the nobles (the conquered peoples they lost = hee-hee, weaklings = not dangerous), but he made all the nobles his friends, and then founded the territorial division into satrapies and prepared the transfer of power to his son. The very king of Mydia, who was last shown to be resentful and suspicious, did nothing against Cyrus, and disappeared from the narrative altogether, and reappeared only at the very end to marry his daughter to Cyrus. In the end it turns out that all the kings, except for the murdered Assyrian — just voluntarily bowed down to Cyrus. Well, that’s because he’s a holy man. And on this holiness holds the whole monarchy.

And the recipe for an ideal ruler is simple — be an alpha-male, a Spartan with combat experience, and that’s pretty much it. You don’t need anything else. Just don’t behave like an egregious bastard. That is, suppress aggression. Of course, for 99.9% of real “I’m a man” Spartans it is very difficult, so perhaps the ideal rulers are so rare. But as much as it may seem like some nonsense, that’s really the whole recipe for Xenophonte. In sum, “Cyropaedia” is the story of how an aristocrat, perfect from birth, received a perfect Spartan upbringing (“Lacedaemonian Politics”), went through military campaigns that made him a “man”, and without making a single misfire in his entire life, and without even once facing a real difficulty to overcome it — created an empire in which he conquered everyone with his perfection and raised a whole nation of superhumans by his example. This sounds like an extended version of the panegyric “Agesilaus,” but I assure you, Cyrus is more like a living human being than the Spartan king-Jesus we’ll talk about next.

Agesilaus — the Son of God who died for our sins.

In the work “Agesilaus” Xenophontes writes a dithyramb to his friend, and at the same time patron and king of Sparta. It is clear that here the Spartan way of life receives no less praise than in the “Lacedaemonian Polity”. Agesilaus is a descendant of Heracles, and his father was a king, son of a king, grandson of a king, etc., etc., i.e. the origin is as aristocratic as possible! Even better than the descent of King Cyrus.

In as much as their lineage is the most glorious in the state, so glorious is their state itself in Hellas.

Besides the fact that the king of Sparta is the best man in the universe and the embodiment of all virtues, Xenophon decides to describe his great deeds as a commander in wars with Persia and other Greeks. Here we see the figure of a kind and religious commander whom even his enemies want to serve, literally as in the Cyropaedia.

Speaking to his soldiers, he often advised them not to treat prisoners [Persians, barbarians, essentially slaves] as criminals, but to guard them, remembering that they too are human beings.

We saw the attitude to slaves as people in the work “Oeconomicus”. But of course, for convenience, we will continue to quote only Aristotle’s words about “talking tools”. Yes, this is a wicked irony and a reminder of how selective quoting works to serve the historian’s own ideas. But that’s not the point. More importantly, in Xenophon’s account, Agesilaus did not even enslave the cities, which made it easier for them to surrender to him without a fight. True, he immediately gives an example of mocking treatment of Persian slaves bought at the market, who were supposedly so weak and flabby that their naked display in front of a crowd of soldiers should have convinced the army that all Persians are weak, and it would be very easy to defeat them. These things do not contradict each other in Xenophon’s mind, and in his other book, the Greek History, the real image of Agesilaus more often than not falls into such contradiction with the idealized picture that Xenophon, with all his effort, fails, and inadvertently reveals the cynical behavior of his patron.

And so, when Agesilaus had already supposedly begun to defeat Persia, as Alexander would later do, suddenly trouble came from the very heart of Greece! Almost all major cities (Athens, Thebes, Corinth, etc.) opposed Sparta, and the king had to return home urgently. On the holy man went … In all his actions the king allegedly never once in his entire life did not make a single mistake … he is literally holier and more sinless than Jesus. And that’s not an exaggeration. In this respect he is like Cyrus, but the latter at least behaved like a human being in everyday life, while Agesilaus is the epitome of stoicism.

When Agesilaus received the news that in the battle of Corinth eight Spartans and almost ten thousand enemieswere killed , he was not at all happy and, sighing, said: «Alas, what sorrow has befallen Hellas! For if the now dead had remained alive, they would have been quite enough to triumph over all the barbarians!”.

But in general, battles and the biography of the king are given a lot of space in this book, and it’s not particularly interesting (you can read the history of Sparta on Wikipedia). At first the idea was to just list what would seem interesting from an ideological point of view here. But alas, there is nothing interesting here at all. This book is simply a listing of all areas of human life to show how in each of them Agesilaus was the best on the entire planet Earth. And he could have the most expensive clothes and the best house, but also the most ascetic modesty, etc., and therefore he would not live in such a house on principle, and would go to a camp tent (this is an exaggeration, and there was literally no such example, but the essence is about the same, the king simply had nothing bad, not only in spiritual but also in material terms). All in all, Agesilaus is one of the benchmarks of sycophancy. It doesn’t add anything that wasn’t already said in the Cyropaedia, but it just adds another example to follow.

Hiero — a most unfortunate tyrant

Xenophon’s dialog “Hiero” is a conversation between the tyrant and the poet Simonides (a kind of “sophist” among poets), where in the process it is revealed that the tyrant is no different from other mortals, and that he even suffers more and enjoys life less than anyone else. Everything from food consumption, to national popularity, is enumerated. And everywhere the tyrant finds himself on the losing end. On the whole, the dialog is very simple, and in a sense still manifests the theme of noble poverty, which is raised in the dialog “Symposium” and even in “Oeconomicus”.

As in “Oeconomicus”, classical sensualism, the compass of pleasures and sufferings, and the theme of the five organs of sensation come to the fore here. It is in a sensualistic way that the benefits for the tyrant are evaluated, and Xenophontes nowhere says that this is something bad, this methodology satisfied him in “Oeconomicus”, and satisfies him now. Even though it is the approach of the Sophists and the hedonist Aristippus. As a result, Simonides (which is strange, given his biography as a “sophist”), having sympathized with the poor tyrant, gives him recommendations on how to become a virtuous and enlightened monarch and earn the respect of the citizens of Greece. But if in “Cyropaedia” idealized the Persian monarch, and in “Agesilaus” — the king of Sparta, here we are talking about a man inherently flawed. It is obvious that Hiero did not go through all the circles of Spartan upbringing.

So, the recipe for success is not complicated. Simonides advises punishments to be delegated to others, and all honors to be done independently in order to win the love of the citizens. The first thing he emphasizes is competition, which should be supported in all affairs, both domestic and public. Xenophontes had already voiced this idea in the Cyropaedia, encouraging soldiers to compete, and it is also heard in his economic works, and not only in them.

And farming, the most useful of all occupations, but also the most unaccustomed to the use of competition in it, will increase rapidly, if in villages and fields to announce awards for those who best cultivate the land, and the citizens, with a special zeal for this turned their energies, will do many other useful things. The revenue will be increased, and sound temperance in the absence of leisure will hasten its return. In the same way, bad tendencies are much less likely to grow in people engaged in business.

True, he admits that trade can be useful for the city of merchants, and competition will give its benefit here too. After all, it is better to be engaged in the business of trade than to be engaged in nothing. In general, tip #1 — a good ruler should motivate people to work better. Tip #2 — make personal bodyguards-mercenaries as servants of the whole state and guardians of order and law. Tip #3 — spend personal funds for the public good; and this is, in fact, the basic advice in general:

For the public good, Hiero, you should not hesitate to spend money from your personal wealth. In fact, I believe that whatever a husband on a tyrannical throne spends on the needs of the city should rather be classed as a necessary expense than his spending on his personal possessions. … First of all, what do you think will do you more honor — a house decorated for an exorbitant price, or the whole city with walls, temples, colonnades, squares and ports? And weapons — what will inspire more fear in your enemies: you yourself, dressed in the most brilliant armor, or the whole city in worthy armor? Take revenues — will they be more plentiful if only your fortune turns, or if you manage to make the fortunes of all citizens turn? … Your competition is with the other chiefs of the cities, and if you alone of all achieve the highest prosperity for the city you rule, be assured that you will emerge victorious from the noblest and grandest competition possible for mortals.

And the reward for this will be the universal adoration not only of your own citizens, but of all the people of Greece, both living and posterity. Such a tyrant will not be despised or considered a bad man. But if he deserves to be in such a high position, then it turns out that in the eyes of the citizens he is no longer a tyrant at all, and his status will change radically. To be a tyrant is to rule badly and to hold power by force. And if everything is voluntary, it is not tyranny. Xenophonte didn’t even quite realize what he had done. He blurred the lines between tyranny and aristocratic monarchy by making the criterion of evaluation solely the partisanship of the leader.

Consider the fatherland as your possession, citizens as your comrades, friends as your children, and do not distinguish your sons from your own soul, and you shall try to surpass them all by your own benefactions. For if thou overpower thy friends in doing good deeds, thine enemies will no longer be able to resist thee. And if you fulfill all these things, be assured that you will be the possessor of the noblest and most blessed acquisition possible for mortals: you will be happy without causing envy by your happiness.

But I was most attracted to the fragments of dialog that speak of love and friendship. In Xenophonte’s “Symposium” Socrates’ company talk a lot about their inner-group relations, and including sexual overtones, so the theme of love here is colored in purely entertaining tones. This may serve as proof for Marxist readers that there was no understanding of romantic love in antiquity (an opinion that is based only on the idealization of the false “meme” that the Greeks, all as one, dissolved their personality in the civic collective, which is refuted by dozens of examples even older than Xenophonte). But in the dialog “Hiero” Xenophont left quite a few fragments about quite traditional, “heterosexual” love with romantic overtones. This and many other fragments from other sources, including ancient lyrics, show that in antiquity there were not only ideas about personality and individuality, but also about romantic love, which, according to Engels, supposedly emerged only in the Middle Ages, together with chivalric romances. However, the theme of romantic love in different angles sounds in almost all of Xenophon’s works, including historical books. Here are examples from “Hiero” on the theme of love:

We all know, of course, that pleasure brings much more joy if it is accompanied by love. But it is love that least of all wants to dwell in a tyrant, for the joy of love lies in the pursuit not of what is available, but of what is the object of hope. And just as a man who does not know thirst, will not enjoy drinking, so he who has not experienced love, has not experienced the sweetest of sexual pleasures. … Take, for example, the reciprocal glances of the one who is seized by reciprocal love — they are pleasant; pleasant are his questions, pleasant and answers; but most pleasant and stimulating to love struggle and arguments. But to take pleasure against the will of the adolescent, is, in my opinion, more like robbery than a love affair. … When a person is loved by others, those who love him feel pleasure in seeing him near themselves; they gladly do him good, miss him in his absence and with the greatest willingness to welcome his return, share with him the joy of his successes and rush to his aid as soon as they notice that he has failed in something.